Analog Revolution

by Deirdre Kelly

photography by Chris Robinson

When everyone grew bored of staring at their screens during the lockdowns, an arts and crafts revival movement took hold – a rebellious reaction to the dominance of the digital in most of our lives. Significantly, young people raised on computer technology were among the first to unplug as they pursued, en masse, more tangible forms of self-expression like crocheting, knitting, quilting, rug hooking and sewing their own clothes. They also resuscitated classic board games like Scrabble and Monopoly, as well as such slow, mindful artisanal pursuits as pottery-making and calligraphy.

“Tactile approaches to anything in life are far more interesting, and more real, than a virtual activity,” says Deborah Lau-Yu (MDes ’08), co-founder of Ferris Wheel Press, a luxury stationery company in Markham, Ont., whose sales of fountain pens, paper notebooks and coloured inks spiked during the pandemic as people took up handwriting again. “They restore us to a more thoughtful, soulful, sensually engaged way of being in the world. The digital age really distances us from that. It disconnects us from the physical.”

“Tactile approaches to anything in life are far more interesting, and more real, than a virtual activity,” says Deborah Lau-Yu (MDes ’08), co-founder of Ferris Wheel Press, a luxury stationery company in Markham, Ont., whose sales of fountain pens, paper notebooks and coloured inks spiked during the pandemic as people took up handwriting again. “They restore us to a more thoughtful, soulful, sensually engaged way of being in the world. The digital age really distances us from that. It disconnects us from the physical.”

A York-trained graphic designer and art director whose own arsenal of artisanal techniques includes vintage letterpress printing and hand-drawn illustration, Lau-Yu is part of a new generation of design innovators returning handcrafted practices of the past to the forefront of cultural activity. Motivating them is digital fatigue, a widely recognized syndrome of feeling overwhelmed by digital devices, apps and subscriptions in the context of the pandemic, where being digitally connected – for both work and pleasure – intensified. A need to take a break from tech now affects more than a third of all households, according to a 2021 Deloitte mobile trends and connectivity survey, and is prompting people to seek out more organic and environmentally sustainable forms of creative expression and engage more of their human faculties than mouse clicks and keystrokes.

With analog photography comes a real sense of mystery – and failure

A return to handmade production represents a return to a simpler life – what trend forecaster WGSN identified in a 2021 survey of youth culture as the catalyst behind a radical shift of habits, hobbies and behaviours in millennials and their younger Gen Z counterparts born between the years 1997 and 2012. In their shared quest for a less techno-laden existence, like the one enjoyed in the decades before social media, this highly influential demographic is making the old look new again. Collectively, they are reviving manual practices and industries thought to have died with the rotary phone.

Sales of sewing machines have skyrocketed in Canada over the past two years – by as much as 200 per cent, according to a CTV newscast – driven in part by “sew bros,” young men who have taken to making their own DIY fashions in the COVID era. Sales of vintage cameras that require real film and labour-intensive darkroom techniques to produce an often deliberately grainy image have also soared, increasing between 42 and 79 per cent during the same period, said Dawn Block, eBay’s vice president of hard goods and collectibles, in a previously published report.

Robyn Cumming (MFA ’07), an assistant professor in the department of Visual Art & Art History, teaches a course on analog photography at York, where the pre-digital photographic technology is used as a tool of creative discovery. “Students are certainly seduced by the tactility and materiality of the analog process,” she says. “With analog photography comes a real sense of mystery – and failure. You need to wait to view what you create, often for days. In a culture of immediacy, forced patience and anticipation can be refreshing. And of course, once you see your results, you’re surprised, excited or disappointed. It’s an emotional process.”

From a psychological perspective, looking to the past as a source of inspiration is a form of resilience, a creative way to cope with our precarious times, says Brent Lyons, an associate professor of organization studies at the Schulich School of Business who studies the impact of uncertainty on individual identity formation. In a situation rife with unpredictability, such as a global health crisis, people are likely to rethink their values and what they want out of life. The collective soul-searching that has taken place since the start of the pandemic in 2020 has resulted in a great many people reassessing their career paths, Lyons says, and ultimately taking up “creative pursuits to help them find connections with people and communities they care about.”

It’s a fresh start, paving the way for new avenues of expression for York grads like Diana VanderMeulen (BFA ’12), a Toronto digital artist who, during the pandemic, moved away from tech-based visual representation to work with her hands as a furniture-maker. Previously, she had been creating apps, videos and computerized still images to document and lend permanence to her environmental installation art. But when the digital became all-pervasive during the early homebound stage of the pandemic, VanderMeulen, a 34-year-old self-described millennial, found herself wanting to shut it down. “I definitely developed digital fatigue,” she says. “As NFTs came into vogue, it turned me away from digital, which to me had become so trend-focused, more about currency and less about art.”

Trained in drawing and printmaking techniques at York, she turned to handcrafting one-of-a-kind translucent furniture pieces made from upcycled Lucite and other found materials, describing the process as “tactile, hands-on, experimental – a different way of expressing myself.” Some of her furniture pieces, including a large berry-coloured Lucite chair, were highlighted at the recent edition of the Interior Design Show’s juried Prototype section for new designers, where she was touted as one to watch. The work is ongoing.

For inspiration, VanderMeulen studies vintage print magazines and, when possible, attends in-person art exhibitions, delighting in getting ideas from a tangible experience as opposed to an algorithm-generated notification of what the internet deems noteworthy. “Tech is amazing and exciting,” she says, “but I want to know what other people are interested in. I want real recommendations based on someone’s authentic experience of a thing, not some bot suggesting to me what it is I should be looking at.”

Tactile approaches to anything in life are far more interesting, and more real, than a virtual activity

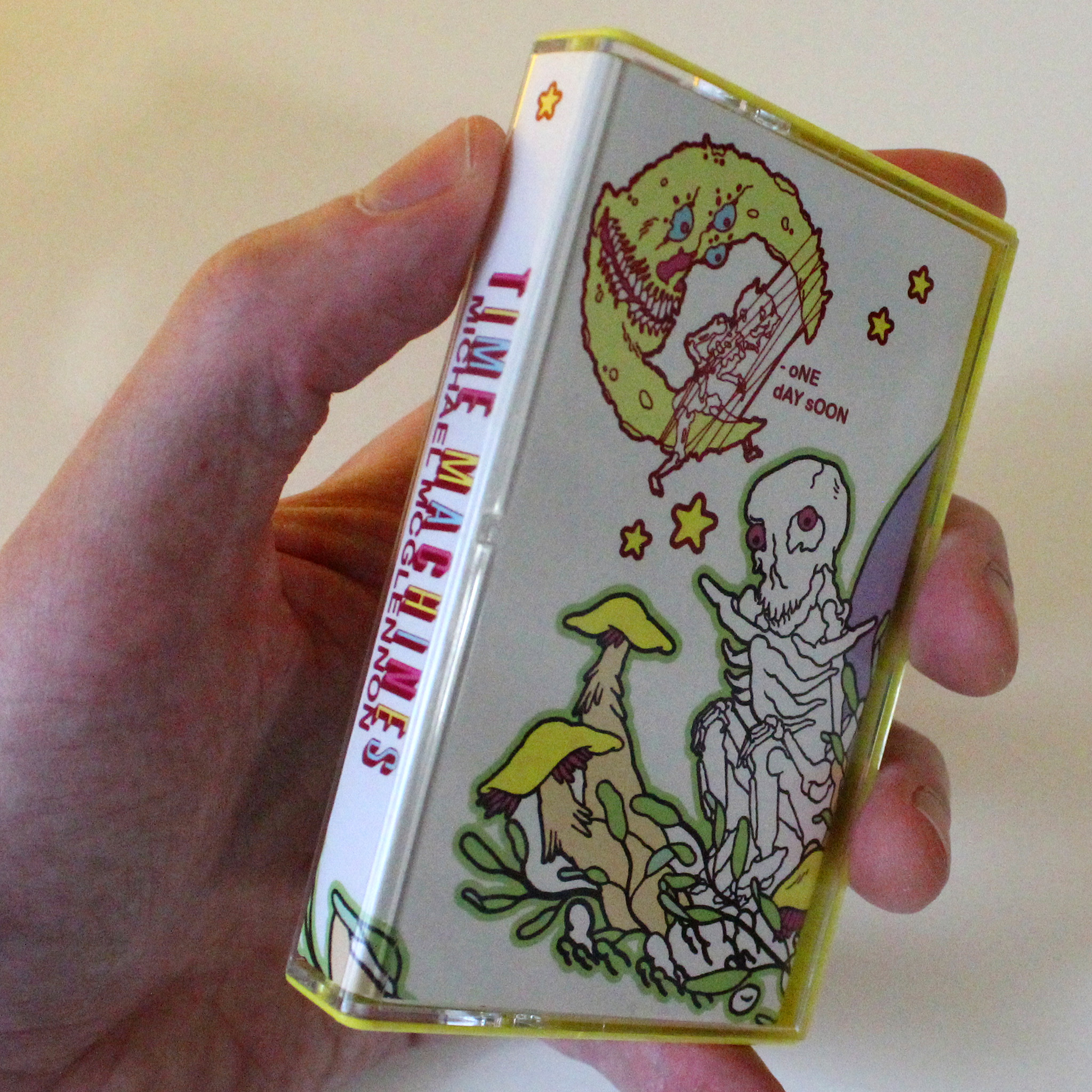

That anti-tech sentiment is shared by fellow York grad Michael McGlennon (BFA ’14), a Toronto illustrator and musician better known by his artistic name, Moon Toboggan. During the lockdowns, he wrote poetry by hand and made and released a new album – tIME mACHINES – on streaming services, as well as on old-school cassette tape. A future project involves a hand-drawn comic book about growing up in Northern Ontario. Much of his artistic practice is deliberately tech-free to better root it in nostalgia. “So much of my work, whether visual, audible or readable, revolves around childhood memories and dreams,” he says. “Even when I’m just sketching or aimlessly playing guitar, a random idea will begin to grow out and bloom once it takes root in the past.”

To Ana Paula González Urdaneta (BFA ’13), a York-trained painter in Mexico City, nostalgia is not just a state of mind but an artistic practice based in centuries of painterly tradition. When she creates one of her colourful canvases, depicting spiralling butterflies or fantastic island landscapes floating on blue waters, she layers image after image by hand using a paintbrush manipulated by rhythmically moving fingers. The repetitiveness lulls her into a state of deep concentration, allowing her to tap into her subconscious and draw upon ideas lurking there, in the depths of her being. This is why, to her, tactility is the key to creativity and feeling at one with the world. Unplugging, she says, reconnects her to the power of human touch. “Handmade art not only carries a human quality that makes it irreplaceable, it also taps into the continuum of human expression through our relationship to and manipulation of materials. For me, the process of building an image layer after layer would not be as satisfying if it were a virtual one. It’s a means to ground myself, order my thoughts and articulate them through a negotiation with something I can hold in my hands.” ■