Seeing Things

by Deirdre Kelly

photography by Mike Ford

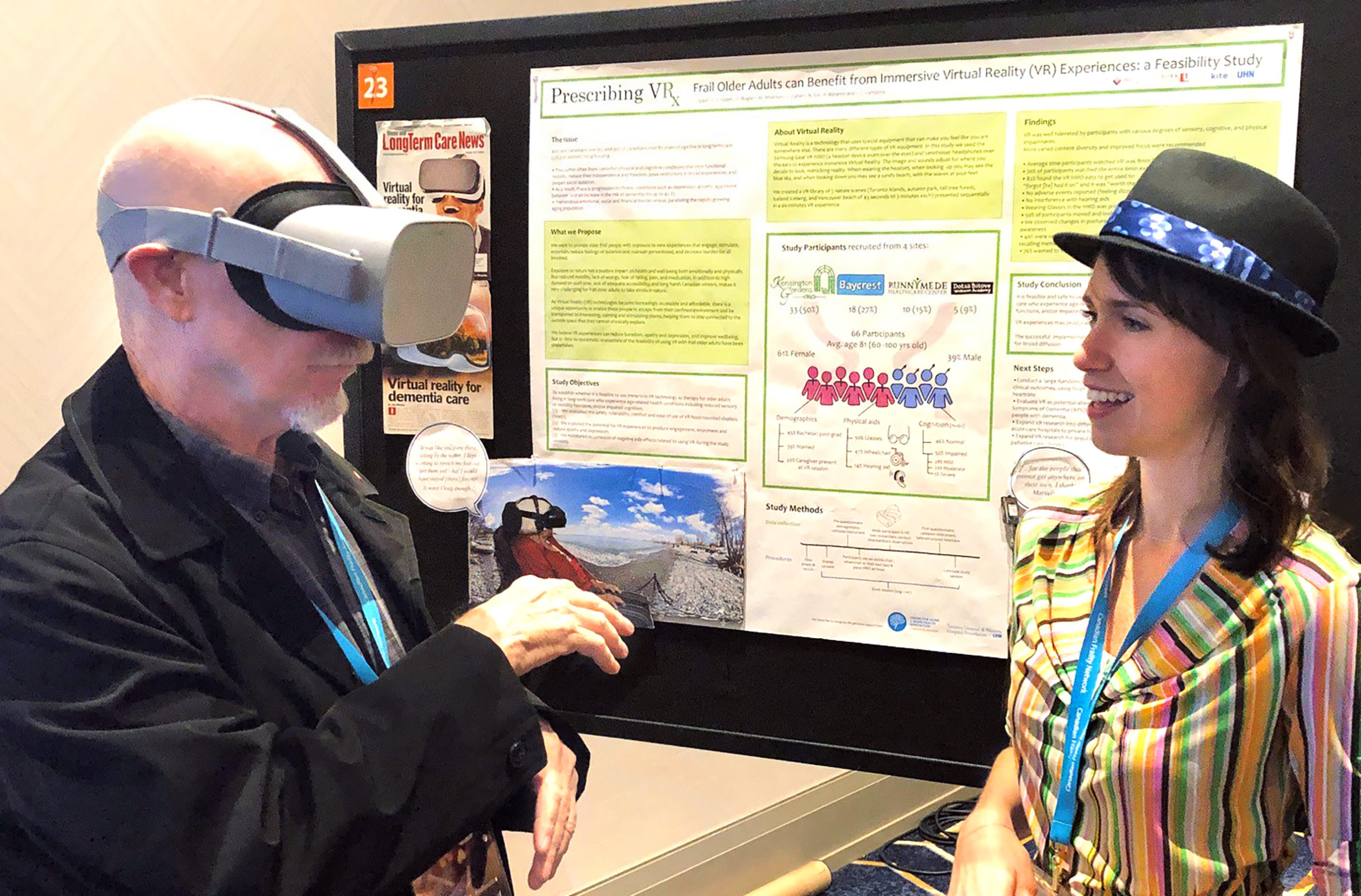

Think “virtual reality” (VR) and the mind goes automatically to gaming. But the simulation technology has numerous therapeutic applications. One of these is reversing vision loss in Canada’s aging population – the current mission of Lora Appel (iBBA ’07), an assistant professor in the Faculty of Health at York University.

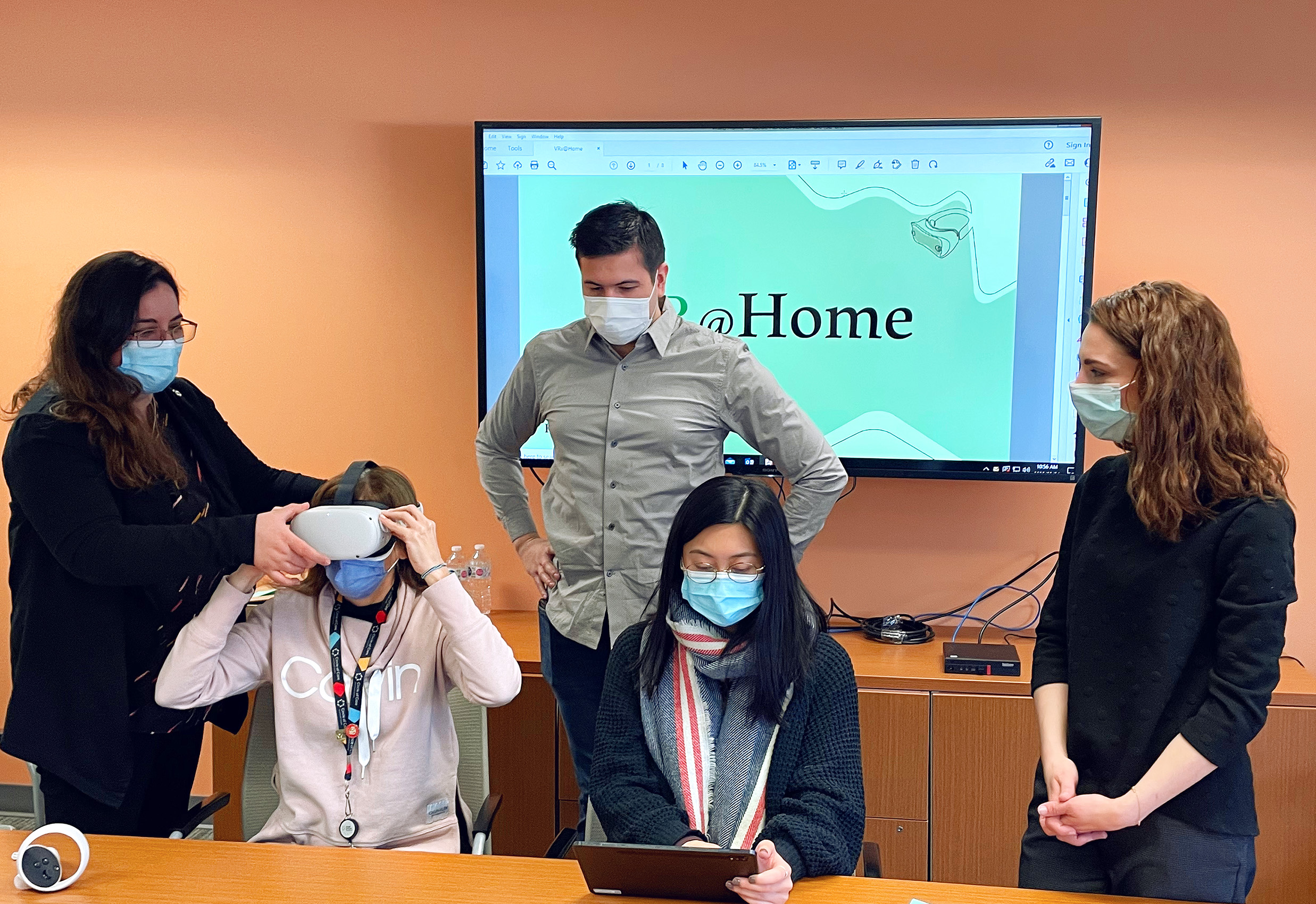

In collaboration with neurobiologist Michael Reber, a senior scientist who developed a VR therapy program for the sight-impaired at Toronto Western Hospital’s Donald K. Johnson Eye Institute, Appel has created VRision, a pilot study using an immersive VR headset to improve vision in healthy seniors with age-related vision loss or vision-related diseases. The first of its kind, the investigation employs an Oculus headset synched to exercises that stimulate the brain and the visual and auditory senses. It launches this summer at Perley Health, an Ottawa-based long-term care facility and research centre.

“More Canadians have age-related macular degeneration – the leading cause of vision loss – than have breast cancer, prostate cancer, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s combined,” says Appel, a graduate of the Schulich School of Business who is also an adjunct researcher at Toronto’s Michael Garron Hospital and collaborating scientist at OpenLab, a University Health Network design and innovation studio. “Non-invasive technological interventions can have a real impact in restoring sight in the older population. Our aim is to determine how VR, as a therapeutic tool, can best succeed in the real world.”

In the program, patients are asked to complete tasks such as following a cluster of animated tennis balls of different colours and varying speeds. Some virtual scenarios are superimposed onto real-life settings, like the busy intersection of Dundas and Spadina in downtown Toronto. The idea is to get those patients who may have lost their driver’s licence due to visual impairment to navigate a landscape that might one day be accessible to them again once their sight improves.

The device is connected through secure Wi-Fi to the team’s lab, which can tweak the exercises in real time, allowing for customization. Initial results show that the VR therapy has real promise. Patients who have already used the device as part of a four-week treatment program claim to be able to read print better than before doing the exercises.

Next steps include creating a comprehensive loaning program where VR headsets can be mailed to afflicted people who live in remote areas and making dedicated VR units available in pharmacies to anyone who might want to use them for screening and, later, even therapy (like those free blood pressure machines). At present, the price of a headset is $500, around what a pair of prescription eyeglasses might cost. “We’re all moving in the direction of equity-based health care,” Appel says, “and VR is helping to facilitate that. It’s mobile, it’s configurable, it’s connected. It’s where we’re all headed.” ■