Alumni

Black Books

by Deirdre Kelly

photography by Joy von Tiedemann

David Chariandy (PhD ’02) was born in the week of the first moon landing, prompting his doubly amazed parents to want to call their newborn Apollo in recognition of the NASA command module carrying three moon-bound astronauts in the summer of 1969.

The original Apollo is the Greek god of poetry, art and music. Given that Chariandy would go on to forge a career in the literary arts, emerging as one of Canada’s most awarded fiction writers, the name, while ungainly, would have fit.

But imagine the lifetime of teasing that would have ensued. Hey! So you think you’re a god? Let me crown you! Chariandy, a professor of postcolonial literature at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, certainly has.

“Luckily for me, they thought better of it,” he says of his immigrant parents who directly and indirectly have served as inspiration for his award-winning books, among them Brother, a recent recipient of the Windham-Campbell Prize for fiction, one of the world’s most prestigious – and, at nearly a quarter-million Canadian dollars, most lucrative – literary awards. “I might have had an entirely different life with a name like that.”

Named instead for the giant slayer of biblical fame, Chariandy started that life nearly 50 years ago in Scarborough, Ont., the east-end Toronto neighbourhood that even the denizens call Scarberia for its unremitting blandness and distance from downtown Toronto.

Chariandy’s parents had immigrated there from Trinidad in the 1960s, joining other families from the Caribbean diaspora and elsewhere who had resettled in a rough and tough area that boasted affordable housing and easy access to parks, shops, schools and wide-open spaces where imaginations, given the right stimuli, could grow.

From an early age, Chariandy’s main stimulation was sci-fi and fantasy literature, which offered him a true escape from the mundanity of his upbringing. His father, who is of South Asian descent, worked in a factory and his mother, who is of African ancestry, as a nanny.

While they might not have indulged themselves in their son’s love of books, they imposed no barriers. Chariandy, who has a brother, went on to become the first in his family to get a post-secondary education.

He studied literature as an undergraduate at Carleton University in Ottawa, doodling around with writing literature of his own on the side. He wasn’t sure he had the writer’s gift and so concentrated on moving through the ranks of academe.

After completing his BA and MA in English at Carleton, Chariandy moved back to Toronto in 1996 to begin a doctoral program in postcolonial literature at York University, lured by the institution’s reputation for scholarly excellence, innovation and accessibility.

“York had a reputable name for the study of literature – critical, theoretical and marginal minority literatures in particular,” says Chariandy on a recent visit back to Toronto to meet with his editors at Penguin Random House Canada to discuss his next novel, involving three different stories exploring the complicated relationships between people of African and South Asian descent, as he described it.

“It also had a constellation of scholars that would and could support a project on Black Canadian literature, a very unusual subject for a dissertation but York backed it all the way.”

“York has an innovative gene,” affirms Leslie Sanders, a professor in the Department of Humanities and who supervised Chariandy’s thesis on Black Canadian writers, past and present.

“It’s the first university in the country to take Canadian literature seriously and that’s back to its founding as a centre of strong Canadian literary scholarship. David has inherited that legacy,” she continues, “and seeing him getting recognition for it is so very satisfying.”

But besides an intellectual education, York also gave Chariandy a sense of community, what he often writes about in his books.

“His fiction and non-fiction reveal the latter-day, latent Creole genius, brooding brilliantly over the Black-&-Tan Atlantic, and never obsequious, never doctrinal, but waving off imperialists’ ruins with singing cataracts of ink,” says the Canadian novelist, playwright and parliamentary poet laureate George Elliott Clarke, whose writing has influenced Chariandy’s literary works.

They include his debut novel, Soucouyant, named for a Caribbean malevolent spirit, which follows a family from Trinidad to Toronto’s Scarborough Bluffs with heartbreaks along the way. Published in 2007, it was nominated for 11 literary prizes, including the Governor General’s Literary Award.

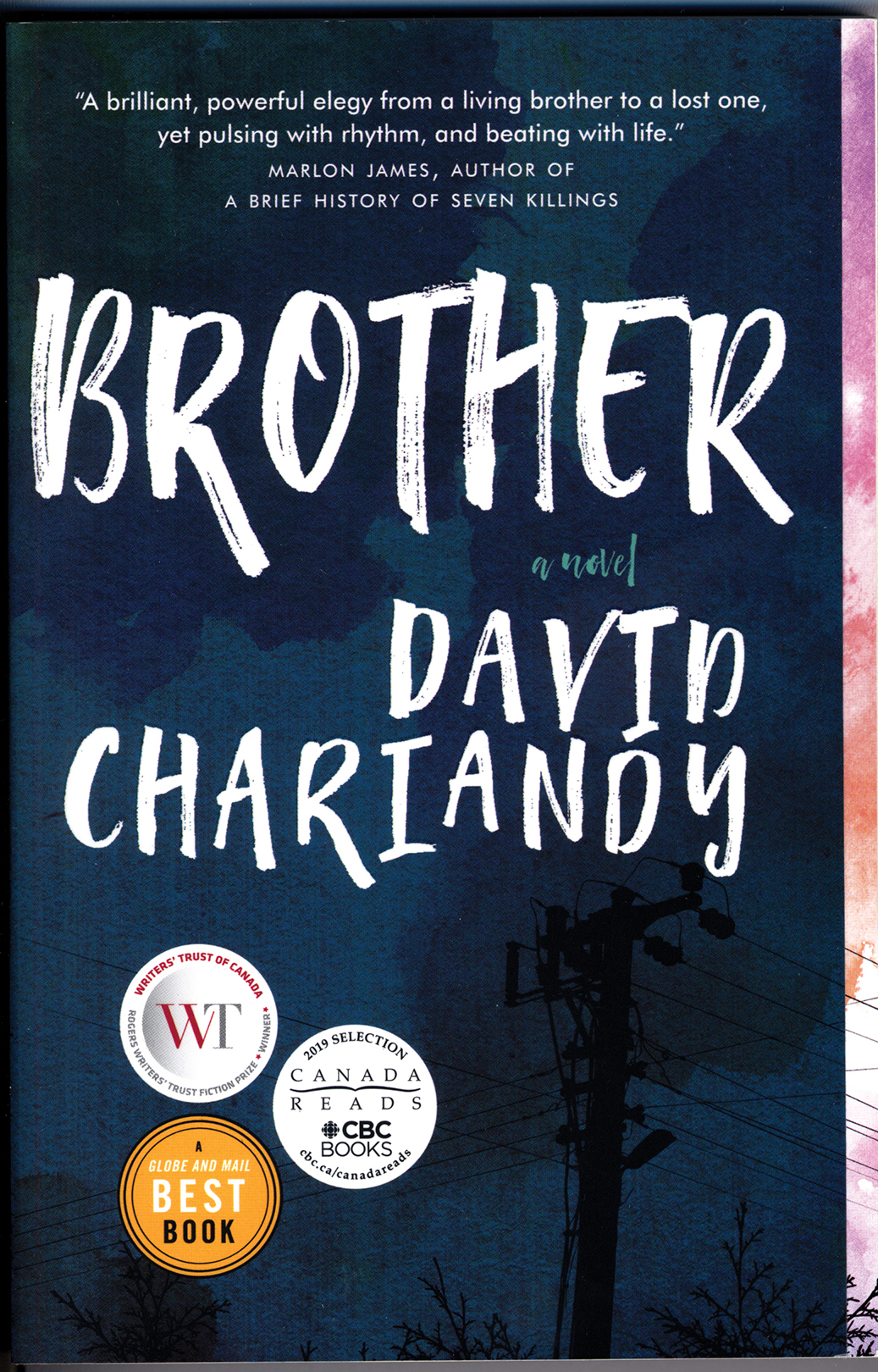

Perhaps more noteworthy is Chariandy’s second novel, Brother, about the sons of Caribbean immigrants who explore issues of race and masculinity in the hot Scarborough summer of 1991. It won the 2017 Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize and the 2018 Toronto Book Award in addition to the 2019 Windham-Campbell Prize to be given out at the Yale University literary festival in September.

More recently, Chariandy, a married father of two, published I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You: A Letter to My Daughter, his memoirs in epistolary form. Like his fiction, the book explores race and family history.

“I come from a cultural and socioeconomic background where the idea of going to university, never mind a PhD, is in and of itself not a given. It’s far from being automatic,” he says.

“Having that privilege has shaped my gratitude for the work done at a university and given me a heightened sense of the work still to be done.” ■