Costume Drama

by Deirdre Kelly

photography by Cylla von Tiedemann

After designing over 20 productions at the Stratford Festival for 18 seasons – and winning two Dora Mavor Moore Awards for Outstanding Costume Design along the way – you might wonder how Dana Osborne (BFA ’96) keeps coming up with new ideas. But the source of her inspiration is old as the Bard himself. In her case, the play really is the thing.

“I don’t think I’ve ever worked with a costume designer like her,” enthuses Donna Feore, the hotter-than-hot Stratford choreographer and theatre director who has two shows at the festival this season, The Music Man and The Rocky Horror Show, both designed by Osborne. “She’s so invested in the text and she reads those scripts in consummate detail. You know how people say they have collaborators? Well, in Dana I really do have one. She wants to make things happen. She inspires me.”

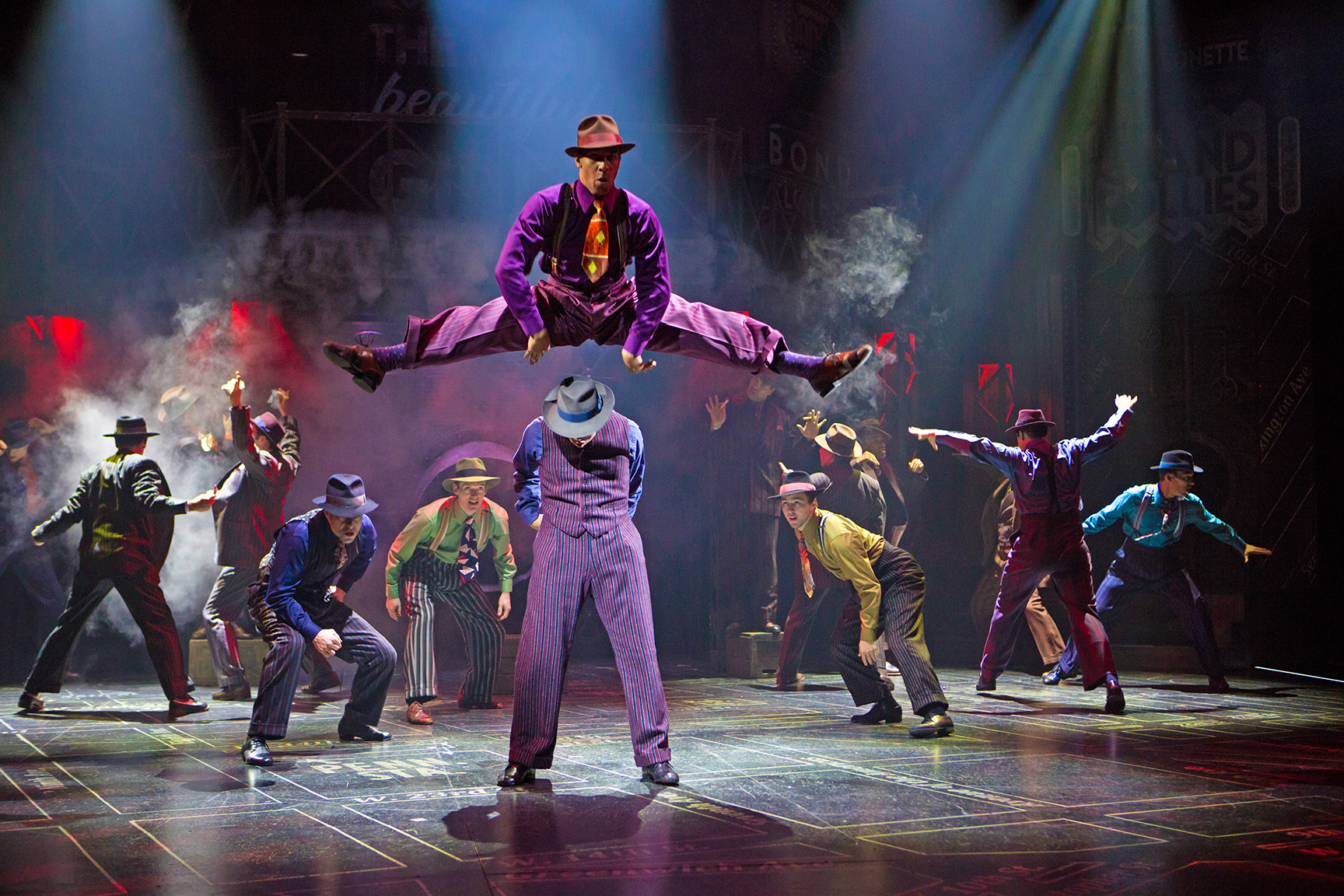

These words of praise, said loud enough so she can hear, make Osborne stick her fingers in her ears and go la-la-la as she strides across the theatre’s thrust stage to reach her fabric and lace ribbon aerie located behind the scenes. Accomplished as she is – her past Stratford shows include last season’s hit musical Guys and Dolls and Timon of Athens, a film version of which (by director Barry Avrich) recently screened at select Cineplex Cinemas across the nation – Osborne has maintained the quiet modesty and decorum befitting her private-school girl upbringing in her hometown of Duncan, B.C.

It was a lot of learning, a lot of social learning. I knew nothing, but I was determined

“You always have to take your ego out of the picture,” says the 43-year-old married mother (her husband is actor Stephen Gartner) of a seven-year-old daughter in the weeks leading up to Stratford’s 2018 season opening at the end of May. “You have to stay true to the production. That’s the absolutely best part of this career – you’re constantly learning.”

That learning started at York, to where Osborne had applied after one of her high school teachers had told her about the University and its progressive theatre program. Prior to that, she had never heard of the University before; she also had never before been to Toronto. “But I was desperate to get away from my small town,” Osborne says. “I wanted to be an actress, and when I got to York I was slightly overwhelmed. It was big, it was diverse, it was very different from what I knew – 23 girls in a class. So, it was a lot of learning, a lot of social learning. I knew nothing, but I was determined.”

The social side of the University ended up being as important as what she experienced in the classroom where she studied not just acting but also set and costume design, a course requirement demanded of her academic discipline. Her roommate at Winters College, where she lived three years, was Meghan Callan (BFA ’96), now Stratford’s stage manager. “She had grown up in Stratford,” Osborne says, “and was the one who brought me here to experience it for the first time.” Also from York – whom Osborne met later – was Jeff Churchill (BFA ’05), today a cobbler who runs a theatrical shoemaking business called Jitterbug Boy. This season, Osborne commissioned Churchill to create the thigh-high platform boots to be worn by actor Dan Chameroy, as Frank N. Furter, in Rocky Horror.

During her final years at York, Osborne had decided to become a designer, as opposed to a thespian, as a way of securing full-time work in the theatre. After graduating in 1996 with a bachelor of fine arts degree, she worked as a costume assistant first on a cruise ship, and then on a variety of big-budget theatre shows, including The Lion King and Mamma Mia! for Mirvish Productions in Toronto. Another great learning experience.

“But it was a lot of pressure,” Osborne recalls. “I lost 10 pounds and ended up getting an eye twitch, and that’s when I realized I missed creating. I wanted most of all to design.” Churchill, her fellow York alum, then told her about an assistant designer program at Stratford. “He said I should apply and I got it. I arrived in 2001, and by 2003 I had started designing.”

Her first show at Stratford was Agamemnon, for which she designed homespun robes inspired by the play’s 2,500-year-old Greek setting. The following year she did evening wear for Stephen Ouimette’s 2004 contemporary-world production of Timon of Athens, and in 2005 the sexy lingerie worn by Cynthia Dale playing Maggie in the late Richard Monette’s direction of the Tennessee Williams’ sizzler Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Many more plays followed – Moby-Dick (directed by Morris Panych, and one of Osborne’s favourite shows), As You Like It, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Hosanna, Man of La Mancha and Carousel, to name only a few.

The multiple Tony award-winning designer Santo Loquasto, an American Theater Hall of Famer who has served as production designer on Woody Allen’s films and more, frequently designs for Stratford where he has had the privilege, he says, of seeing Osborne in action. He thinks she’s a one of a kind.

Dana has always brought a keen contemporary sense and sophistication to her productions…. a kind of visual energy that entices the audience

“We met at Stratford where she was one of several bright, talented designers. And during the seasons I worked there I saw her grow in confidence and expertise, not only in command of the play but the players as well. She is a true friend and colleague and it delights me to see her work deservedly acknowledged,” says Loquasto, which, coming from him, is high praise indeed. “Dana has always brought a keen contemporary sense and sophistication to her productions. What we used to refer to as personal style. At Stratford, this was particularly exciting to see. It’s a kind of visual energy that entices the audience.”

Osborne can’t la-la-la that one out. But, with a goofy grin and a shrug of her lanky shoulders, she waves off the accolades and focuses instead on the hard work that goes on backstage to create the enticement that so bedazzles the shows she designs.

The process starts with a yearly shopping trip to the garment district of New York where Osborne becomes like the proverbial kid in a candy shop, scooping up bolts of fabric for the season’s productions. Given that her Stratford shows this year are so different in tone, content and atmosphere – The Music Man, Meredith Willson’s wholesome 1950s musical, is about a con man named Harold Hill who poses as a boys’ band leader in order to sell instruments and uniforms to the unsuspecting residents of a Midwestern U.S. town, while The Rocky Horror Show is a lurid 1975 punk rock-meets-horror show spectacle in which a cross-dressing mad scientist seduces a couple who arrive at his costume party after their car breaks down in the rain – Osborne had to split her purchases in two.

On one side were piles of pastel-hued cotton, gingham and silk; on the other enough spandex, fishnet and pleather to pleasure a vegan drag queen. “I can’t use natural fabrics all the time,” she says, “because I have to make things that can last 120 shows.” Once back in Stratford, Ont., the town located about 90 minutes west of Toronto, and Osborne’s home since 2011, those fabrics – manmade or otherwise – were cut and hand-sewn by a team of expert assistants according to Osborne’s designs. Even after the costumes were done, adjustments were constantly being made, right up until the day of the performance.

During dress rehearsals for The Music Man, for instance, it was discovered that the silk petticoats Osborne had designed for performers to wear under their twirly dresses were too heavy to allow for complete freedom of movement during the production’s high-kicking dance numbers. Osborne then went promptly back to the cutting room table, fashioning new costumes made from a lighter-weight polyester that upped the energy level without compromising on the show’s overall look. She had trained in dance back in B.C., and so has an innate understanding of how a costume needs to move and breathe when it is on stage.

“A costume does not succeed,” Osborne says, “if it is not one with the actor. It’s got to look like the actor owns it, otherwise there is no point.”