Let’s Hear It for Oscar Peterson

by Deirdre Kelly

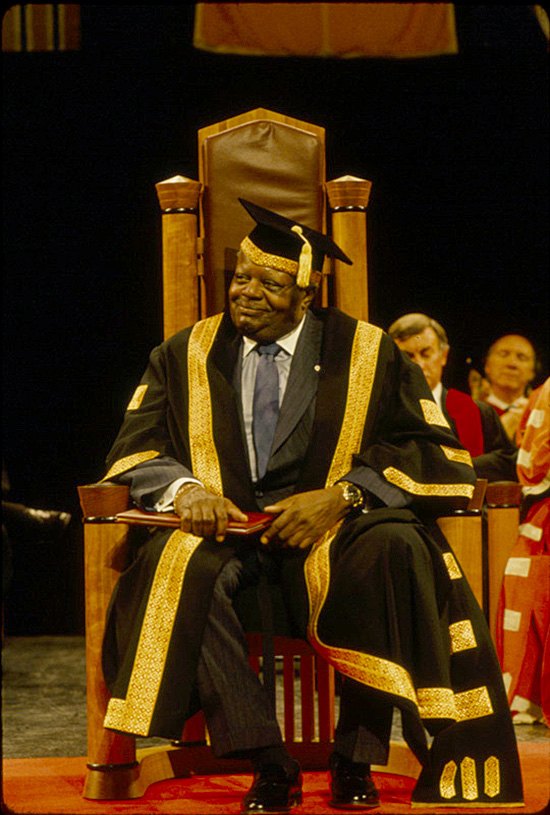

In the new Canadian documentary Oscar Peterson: Black + White, no less a music authority than legendary producer and composer Quincy Jones declares the late jazz legend to be the greatest there ever was. His testimony is borne out by footage of Peterson, then an adjunct professor in York’s trailblazing jazz music program, burning up a piano keyboard at York University – where, in 1982, the Order of Canada recipient received an honorary doctorate for his immense contribution to Canadian culture.

In 1991, the ex-Montrealer was sworn in as the University’s ninth chancellor, another historic moment captured in Barry Avrich’s latest film, now streaming on the Crave TV network.

“Just watching Oscar play is a wow,” says Avrich, an award-winning documentarian and advertising industry veteran who is a former guest lecturer at York’s Schulich School of Business. “He could go a hundred miles an hour but then switch gears and be so soulful. There really was no one like him.”

There’s a lot of Oscar out there right now, and it’s about time

Peterson died in 2007, at the age of 82, leaving behind an immense musical legacy that is finally getting its due. Besides Avrich’s film, whose world premiere took place at the 2021 Toronto International Film Festival, there is a new Oscar Peterson public square in downtown Montreal, an Oscar Peterson Heritage Moment on Historica Canada, an all–Oscar Peterson channel on Toronto’s JazzFM and the renaming of the Royal Conservatory’s community school as the Oscar Peterson School of Music.

“There’s a lot of Oscar out there right now, and it’s about time,” says associate professor Ron Westray, since 2010 the inaugural Oscar Peterson Chair in Jazz Performance at York University. Westray, a native of South Carolina, is the author of Life in Reverse: Tales of a Very Stable Narcissist, a new book about spending time on the road as a jazz musician.

A trombonist and composer, Westray adds to the ongoing celebration of Peterson in an interview he conducted with Avrich, a fellow O.P. fan, exclusively for The York University Magazine. Their conversation – touching on one-take performances, the art of the sell, and all that jazz – follows.

RON WESTRAY: You’ve moved pretty fast for a guy who’s not yet 60. I mean, you’ve done quite a bit. You’ve directed and produced a long list of TV specials in addition to more than a dozen documentaries, plus a few more in development. So before we get into our chat about O.P., tell me how you came to be a filmmaker and how it led to the film we’re talking about now?

BARRY AVRICH: I was lucky to have been born into a family that valued culture. We lived in Montreal, and it was a very small, simple home, not a lot of money. But without university degrees, both my parents [Irving, who worked in the garment industry, and Faye, a homemaker] understood the currency of culture. They understood theatre, they understood music and they understood film – not the theory of it all but the sheer ability of the arts to transport people and make them think and feel. As far as music goes, we had about six albums at home and that was it. But they were well-chosen: Ella, Oscar, Frank, Tony Bennett, Sarah Vaughan.

RW: What about film? Was it an early calling?

BA: I did want to be in the film industry from the age of eight. I’m not sure why. My father would often take me to the movies and he would always tell me to watch the audience, not the film. I remember saying to him, “What does that mean, dad?” And he goes, “Well, it’s all about the pacing and the editing and the knowing when your audience is losing focus.” He was in the clothing industry, where he would regularly present a season of ladies’ sportswear, watching how people were reacting to colours and fabric. It was the same thing for him with film, and so I became enamoured of it. But there wasn’t any defined path of me going to film school at UCLA or New York. There was none of that.

RW: So how did it end up happening?

BA: I had an uncle who was a dreamer like me. He never really accomplished much, but he accomplished enough to set me on the right path. He told me that if I was going to stay in Canada to work in the film industry then I was going to die. You have to realize that this was ’70s, when pretty much all you had was the National Film Board doing films about the gestation period of the Canadian beaver or the migration patterns of Canadian geese. So this seemed very much to be a dead end. But then my uncle showed me a September issue of Vogue magazine, saying, “This is where you really want to be.” “What?” I said. “What do you mean?” And he said, “Advertising.” You can have an issue this thick with 500 ads and never want for anything. And so I took his advice. For over 32 years, I’ve had a parallel career in both advertising and film, and it has served me well. Everything I’ve done in advertising is somewhat cinematic, and everything I do in film is edited like a commercial. Because that’s what I like.

In my pantheon of jazz idols, he’s kind of at the top

RW: The relationship between advertising and film really comes through in your Oscar doc, from the way it unloads to the quick transitions and almost retro aspect of the graphics. It really sells the subject. You’re immediately hooked.

BA: In advertising, you have between 30 and 60 seconds to be impactful – or, nowadays, 15 seconds or less if working in digital – and so grabbing the audience’s attention is harder than in film, where you have the breadth of a much larger canvas to communicate your story. So I’ve learned over the years not only packaging and selling but pacing too. With this film, when I sat down with editor Nicholas Kleiman and producer Mark Selby, I had only one direction, and that was “freight-train.” I said, “I want this thing to move and never stop.”

RW: That’s exactly how it rolls along. I mean, it takes you there by means of a lot of footage and you never get stuck. But there is a rest station, if you will, in the form of a contemporary musical ensemble. Can you say anything about that?

BA: I call my Oscar film a docu-concert. In addition to footage of Oscar in performance, it features a group of musicians, both established and emerging, who play music he played in his lifetime. I was inspired by some other very good films that also include live music: Standing in the Shadows of Motown; 20 Feet from Stardom.

RW: Were you ever fortunate enough to have met him, or is this all a kind of homage?

BA: I had seen Oscar perform multiple times when I was younger, with my mother at Place des Arts, where we were very much aware of his Montreal roots. I certainly didn’t ever have a relationship with him beyond that. But my mother, who is now 92, has recently disclosed that there is a deeper connection, and it’s through the family. Oscar’s father worked for CN on the trains as a porter, and my grandfather’s brother worked on the trains as well, also out of Montreal. My grandfather was a kosher butcher, and often he would give meat to the Peterson family through his brother. So somewhere along the line, Oscar ate kosher and we were responsible! But beyond that, no, I never met him. But in my pantheon of jazz idols, he’s kind of at the top. Diana Krall, whom I had the great fortune of filming last fall, calls Oscar one of her piano mentors, and so I’ve gotten to know him better through her.

RW: Yes, I’ve also lived vicariously through her development in Oscar-influenced jazz. I would say that he’s been a mentor to almost every jazz pianist after him, in some sense. And his mentor or inspiration was Art Tatum, whom you have included in your film. But who, in your opinion, had the fastest fingers to run across a keyboard? Who wins the competition?

BA: Right. Oscar Peterson and Art Tatum. Well, the backstory on that is that Oscar’s father, to encourage him, brought home an Art Tatum album for Oscar to listen to. He heard that album and afterwards gave up the piano for a month, saying to himself, “I’m never going to be that good.” Yes, Tatum absolutely was a brilliant pianist and showman. I’m not a musicologist, and people can write all the letters they want if they disagree, but I think where Oscar sort of won out is by being a deeper composer, and his ability to put together musicians to play with him, those legendary trios. It’s quite spectacular to see that in the film – his ability to curate a great performance and not necessarily make it about him. He was a very generous musician – and I’m not saying Art wasn’t. But I think Oscar was the more soulful pianist. He could switch gears and sing too. So it is a tough comparison, but in my opinion, Oscar wins the competition, if there even is one.

RW: As for advancing styles, Oscar refined and extended Tatum’s language. He took what Tatum had and applied it to the next progression of jazz. He went beyond Tatum.

BA: You’re absolutely right. I think Tatum taught Oscar the fundamentals, the power of the piano, that lightning ability to play and get lost in it, which is so extraordinary, and then Oscar took it another step forward in terms of composition and the sheer volume of his discography. There are tons and tons of Oscar recordings, and then another 200 albums of other people’s recordings, and they all have Oscar playing accompaniment. I think it’s often forgotten that he was the guy that everyone from the Duke to the Count to Nat King Cole wanted to play on their records. He was the gold standard.

RW: Sure. I like the part in the film where that comes up – Oscar’s ability to be that sideman despite his enormous stature. He had just enough ego to do what he did, but there’s also so much humility there. A great example is “Just One of Those Things,” where he plays backup to Louis Armstrong but still manages to produce a thing of beauty, even in the shadows.

BA: He was not a diva. Again, that’s why I think this is a different kind of film. It’s not Leaving Neverland. It’s not Miles Ahead. It’s not Chasing Trane. There is no needle in the arm. There is no scandal. As Oscar says at the beginning of the film, “I came to play.”

RW: That’s it.

BA: Yes, that is it. Sure, there are wild, fun stories on the road. But he just really enjoyed what he did. And that is captured by the film. It’s not about tension and drama. It’s about the sheer genius of Oscar and getting lost in his music. That’s what this is.

It’s not me telling the story. It’s Oscar

RW: The American musicians obviously served as a template. But it really is amazing that he did not imitate some of the habits associated with a lot of his heroes. Do you think that was just part of his personality, or was it his Canadianness that protected him from the foibles of the American artists?

BA: It’s a good question. I think it’s partly that. But it’s also his father. You know, a strict upbringing on top of his dedication to the craft. I think Oscar was so committed that he just did not go down that road, and thank God.

RW: Certainly not to the degree that it became part of musical history.

BA: I mean, what do you want to be remembered for? What’s on your Wikipedia page? I think he understood that the minute something horrible happens, that offence goes right to the top of the page. Not that Oscar had to worry about this. He will be remembered as jazz royalty. Period.

RW: Indeed. In regards to the Oscar footage shown in the film, are we seeing things not seen before?

BA: People ask me, “Why you? Why are you telling the story?” And my answer to that is, it’s not me telling the story. It’s Oscar. So to make that happen, we went around the world to find footage that never has been seen before, including interviews in Japan, Scandinavia, across Canada and the U.S., to let Oscar tell the story at different stages as his career developed. So, yes, there is a lot of footage that hasn’t been seen before, and there are a lot of stories that haven’t been heard before, as well as some recordings that have not been aired in decades. It was also very important for me to bring together a group of musicians who play throughout the film as a form of tribute – Robi Botos, Joe Sealy, Larnell Lewis, Denzal Sinclaire, Dave Young and, of course, the great Jackie Richardson. If I did nothing else in my career but film Jackie Richardson perform Oscar’s “Hymn to Freedom,” I would die happy. If I remember correctly, it was one take.

RW: Wow! Oscar actually talks in the film about not rehearsing the soul out of a piece of music, and clearly she knows about that too. So indeed you were really trying to avoid anything that was already known.

BA: Yes. I always try to stay fresh. I didn’t want to regurgitate the encyclopedia entry on Oscar. But at the same time, I wanted to show the entire breadth of a life in 82 minutes.

RW: The film basically moves chronologically, right?

BA: It’s not a straight chronological play. We open, obviously, at where he came from – St. Henri in Montreal – but then we get to his style, what was his sound like, his ability to put trios together, the situation of confronting racism while travelling in the American South, his stroke and ultimately his death. So it’s not a hundred per cent chronological. We move around. Still, there’s a beginning, middle and end.

RW: There’s a lot of Oscar going down in the film for sure, including his ability to be authoritarian and at the same time democratic when leading bands and allowing other musicians to shine.

BA: You know, it was Duke Ellington who told him that he should think about going out and playing solo. He hadn’t even thought of that before, because he had looked at all the other great musicians, who always had trios and quartets; that’s how he built his career. And we look back at that, at the sheer brilliance of his choice of musicians coming in and out of his life. There are really no missteps in the people he selects for the trios – Ray Brown on bass, Herb Ellis and Joe Pass on guitar, Ed Thigpen on drums, etc. They all work well together. They know when to come in and let Oscar power through, and he knows when to give them their solos. It’s just this brilliant symmetry shining through on every album and in every performance. It wasn’t a Buddy Rich thing or even a James Brown thing of saying, “Hey, you’re backup to me.” It was never that. Oscar understood each instrument, he understood composition and where everybody needed to shine and have their breaks, have their moments. Norman Granz, his promoter and mentor, was also very good at suggesting various musicians along the way that might fit in well with him. They all stood with Oscar as long as they could.

In Canada, York was among the first universities to have a serious jazz program as part of its music curriculum

RW: When Duke Ellington told Oscar to go solo, it must’ve been after he had sat there listening to that left hand of his, the boogie-woogie foundation of his art. It’s his little thing. And then the right hand is playing honky-tonk – in the right hand, you know what I mean? You hear that and you always know it’s Oscar.

BA: I think Ramsey Lewis says it best when he talks about never before seeing anybody play all 88 keys the way Oscar could, with those hands covering the whole board.

RW: It’s pure locomotion in that left hand, man.

BA: Billy Joel says in the film that it’s so lightning-fast that you can hardly believe it. It just wasn’t standard. Why else would Quincy Jones, Herbie Hancock and Ramsey Lewis, all of them legends who themselves have consistently pushed the envelope, be so appreciative of Oscar’s legacy? Oscar had range, and I think they admired that. Even after he has a stroke, he starts to experiment with synth and computers and figure out what the next evolution in jazz is going to be.

RW: That’s a great segue into York University, also a jazz innovator. In Canada, York was among the first universities to have a serious jazz program as part of its music curriculum. Oscar came to the University late in his career, first as an adjunct professor and later as Chancellor, aware that York was a forerunner in jazz education. This strong connection led the Ontario government to endow York with the Oscar Peterson Chair in Jazz Performance. You show footage of Oscar at York in your film – I recognize some of the venues. But in the course of your research, did anything else about that relationship reveal itself?

BA: Look, I wasn’t going to ignore that. I was well aware when I moved here from Montreal, a long time ago, where York stood in terms of the arts, compared to other universities. It was U of T in terms of classical music and the Royal Conservatory. But in terms of jazz, dance and drama, it was York. So I knew of Oscar owning that space, of York owning that space when it came to jazz, and so I was very happy to include that in my film. When you think of Oscar Peterson and an educational institution – and he received many honorary doctorates from other institutions – you think “York.” That’s why I included that in the film. I’m very proud of that. And the Peterson family recognizes the association. If anyone’s going to carry the flag for jazz, it’s Oscar and York, and vice versa. ■

This interview has been edited and condensed.