Crash ’n’ Burn

by michael todd

photography by mike ford

The late 1970s were a key period for Toronto. It was a time when the city thought of itself as Canada’s most important art centre. But as Philip Monk, director and curator of the Art Gallery of York University (AGYU), illustrates in his new book, Is Toronto Burning?, history has shown that the nascent downtown art community – not the established uptown scene of commercial galleries – was where it was happening.

It was a political period. Beyond the art politics, art itself was politicized in its contents and context. Art’s political dimension was continually polemically posed – or postured – by artists in these years. It was a period rich in the invention of new forms of art. Punk, semiotics and fashion were equally influential, not to mention transgressive sexuality. With no dominant art form and the influence of New York in decline, there were no models. It was, as Monk points out, a time when anything was possible.

The York University Magazine spoke to Monk about living through a time when Toronto’s art scene went from staid to avant-garde.

THE MAGAZINE: What was the impetus for writing a book and curating a show at the AGYU in which you document what you contend was the life and death of a seminal Toronto art scene in three brief years in the late 1970s? I take it it would be more than just nostalgia on your part?

MONK: Until very recently, there has been a resistance to writing any sort of history of the origins of contemporary Toronto art. I thought it important, while I still had access to resources, to document through an exhibition and interpret through a book what was important about the late 1970s – a time, coincidentally, when I entered the Toronto art scene as a critic. Being a participant gave me other than an historian’s objective perspective, but neither the exhibition nor book were exercises in nostalgia. Rather, the book attempts, like any historical exercise, to chart retrospectively a different path than what the original participants thought they were doing at the time.

THE MAGAZINE: Do you see the book as a document of the time or do you hope it will be more than that? And, further, what relevance might it have for emerging artists now, especially as we’re in the latter stages of this current decade in much the same way that your book documents the latter stages of the Toronto art scene in the ’70s?

MONK: The late 1970s Toronto art scene created itself out of a vacuum, as a performance of sorts with artists as the audience. In other words, it was a performative act that made a fiction of an art scene into a real one. As such, it is a lesson of sorts, a paradigm, in fact, in how to create an art scene. Yet paradigms shift. So much has changed that the late ’70s scene no longer functions as a model. It now really is history alone.

To establish this history in writing is more than to document it. Thus, the book participates in some of the same performative strategies artists employed in the period: In order to make people interested – in what is now historical – you have to mythologize it first. My book is as much myth-making as history writing.

THE MAGAZINE: You call this period in Toronto’s renaissance one of the “last avant-gardes.” Why is that? And do you feel the Internet – where everything can be known and posted as soon as it’s conceived – has taken some of the mystery out of happenstance or random discovery or, indeed, scuttled the whole idea of an “underground”?

MONK: My theory is that for a brief moment in the mid-1970s, avant-garde scenes around the world liberated themselves from the dominance of New York. With its emphasis on video, performance and a pervasive camp conceptualism, Toronto fully qualifies as a leader, having invented some of the strategies that New York artists would then go on to claim for themselves in the 1980s. But to be successful, an avant-garde or underground scene, paradoxically, can’t be too visible. As it draws more people to it, as in the case of Toronto becoming the Queen Street art community, it sows the seeds of its own destruction. This particular art scene decomposed decades ago for reasons other than the Internet, but the immediate exposure the Internet circulates, I believe, is one condition for the present unsustainability of any idea of an avant-garde or underground art scene. Though we mistakenly continue to think within the trajectory of the historical avant-gardes, completely other conditions of cultural production rule now. This is part of the paradigm shift.

THE MAGAZINE: Is the book in any way a mourning about the move from an analogue culture to a digital one?

MONK: As part of a generation that has lived half a life in each era, I recognize how our perceptions and sense of temporality are shaped radically differently. Ditto for our sense of sociality. Part of my nostalgia perhaps is for a period whose sociality was not so captured by or entwined in the daily depredations of capitalism – think cell phones, Facebook etc. Not that capitalism could be escaped entirely. In the past, an underground art scene could only exist parasitically on the larger social system. But that was its freedom.

I am struck by the coincidence of publication of Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida in 1980, with its famous phrase “that has been” applied to historical, i.e. analogue, photography precisely at the moment of the medium’s transition to digital, with the demise of this art scene. Here, perhaps, is my nostalgia for the “that has been” – that the demise of the Toronto art scene corresponds as well to the end of the analogue era.

THE MAGAZINE: The book’s title is interesting one. How exactly was Toronto’s art scene both made and, interestingly, unmade in the space of the years 1977, ’78 and ’79? What forces were at play? The web, for instance, was still a long way off.

MONK: The late 1970s was a volatile period, with economies still in severe recession due to the 1973 oil crisis. New York City and Britain were virtually bankrupt. The punk slogan “no future” summed it up. It was also the radical chic moment of the Red Brigades in Italy and the Red Army Faction in Germany. Toronto, too, was infected by a generalized Maoist/Marxist moment in contemporary art. So I distinguish between an art politics whereby Canada’s then most famous artist-run gallery, A Space, was taken over in a “palace coup,” which led the disenfranchised to open a slew of new endeavours elsewhere in Toronto; and a political art whereby, for instance, A Space’s rival, the radicalized Centre for Experimental Art & Communication (CEAC), advocated knee-capping à la the Red Brigade, which fomented a media and political circus resulting in the loss of their funding and the building they owned, purchased with the help of Wintario. What is interesting in the conflicts and oppositions between the two Toronto cliques – on the one hand those representing performative frivolity and the other political earnestness – were the postures they shared in their fashion for politics or penchant for posing.

THE MAGAZINE: What part did the artist collective General Idea have to play during this time – that is, in getting Toronto’s art scene considered seriously on an international scale?

MONK: General Idea were central to this myth-making moment when the downtown art scene created itself in Toronto. The collective not only articulated the scene’s performative strategies in their own work (the 1984 Miss General Idea Pageant and Pavilion), but disseminated images of this semi-fictionalized scene in their LIFE-like artist magazine, FILE, which was circulated to the whole international “mondo arte.” Who knows what the world thereby thought of Toronto, but such dissemination of images of the scene drew artists from across the country to join the Toronto art community.

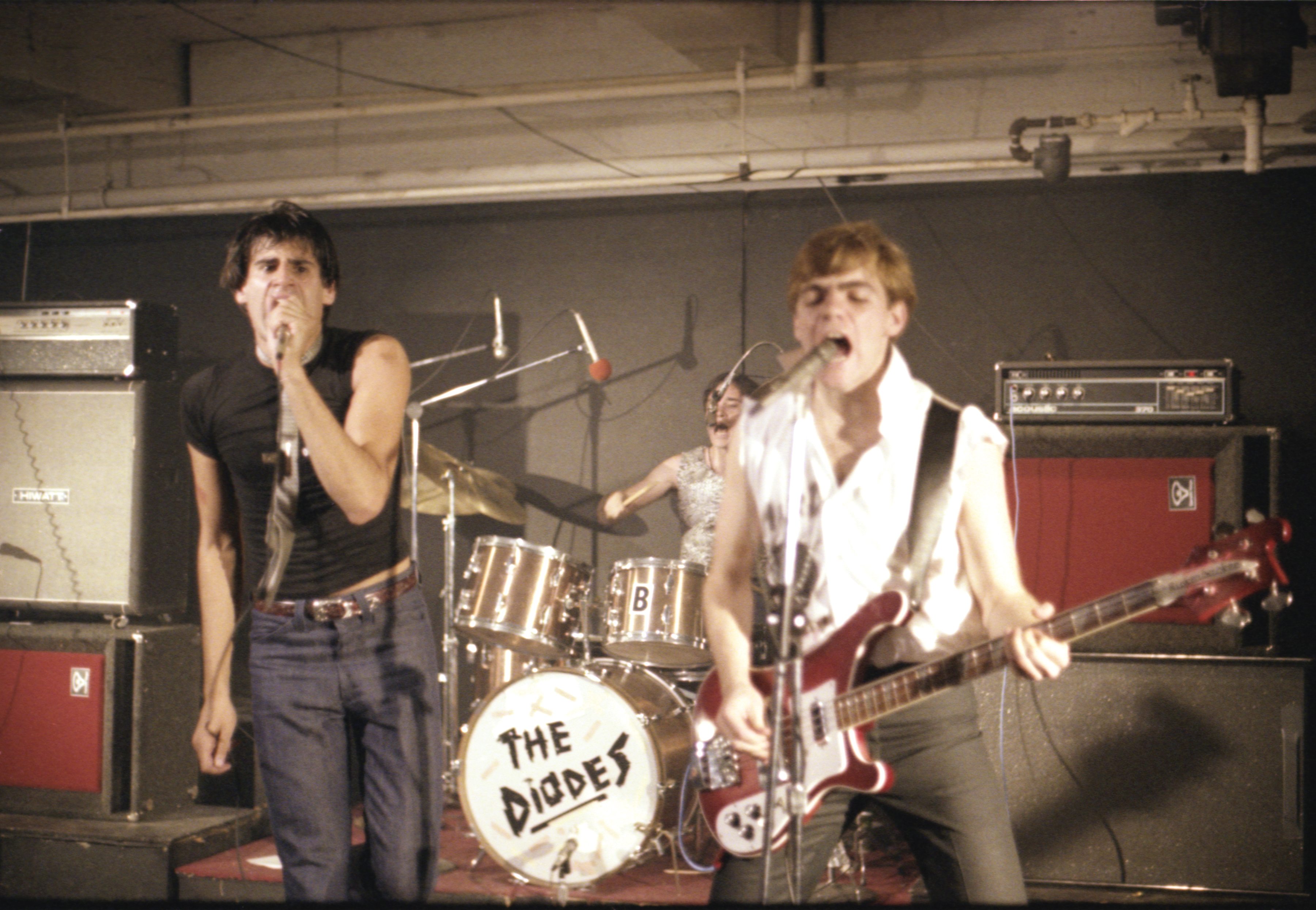

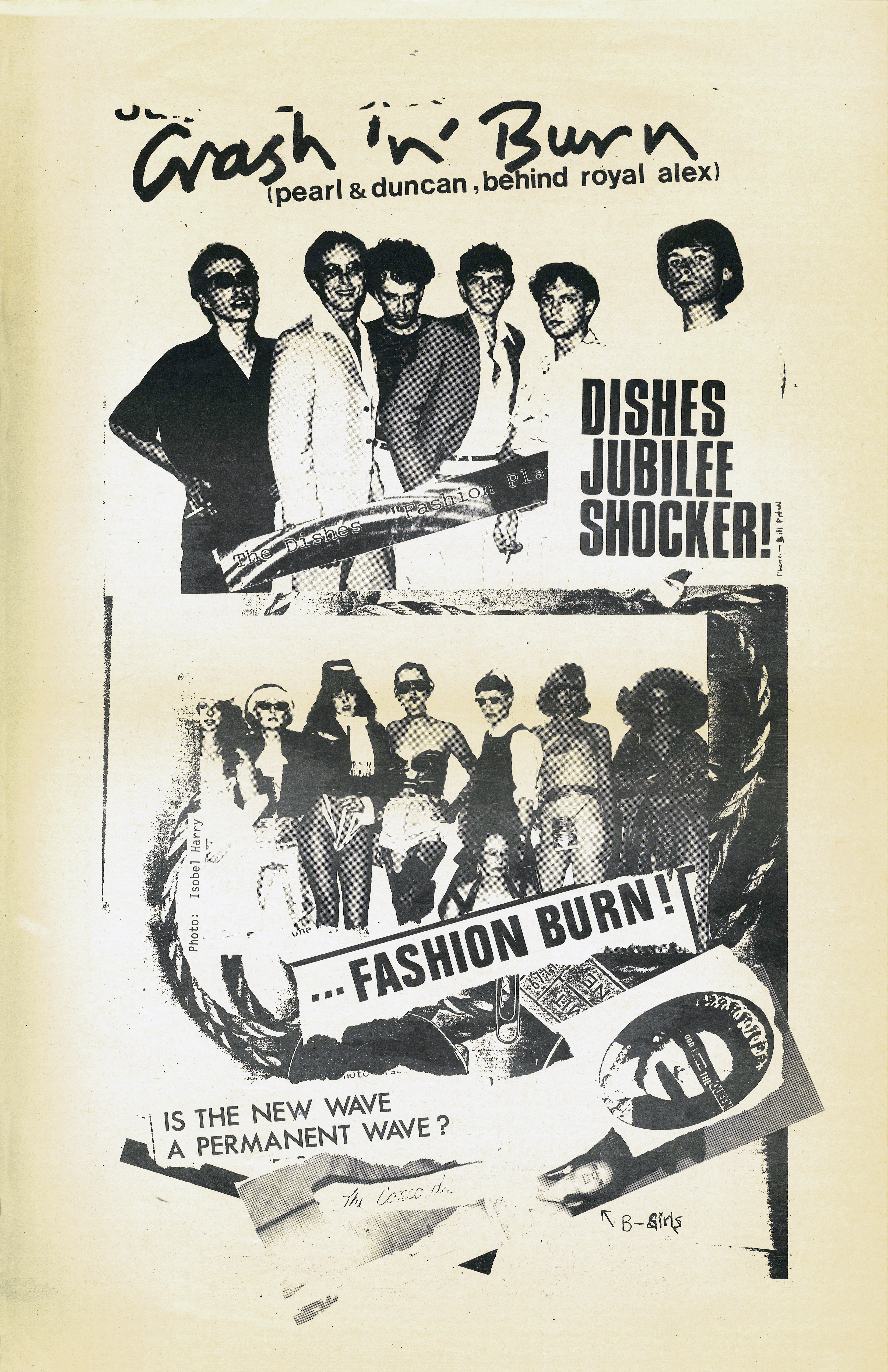

THE MAGAZINE: There was a lot of band activity during this time: The Diodes, who played at Toronto’s Crash ’n’ Burn club, I believe; The Viletones; and later Martha and the Muffins; and others, as punk began to cross paths with ’80s synth-pop. What kind of influence, if any, was that having on the visual or performance art of the time? It seemed to be a time of great theatricality and excess, especially in music and fashion as glitter and glam gave way to new wave.

MONK: As with Warhol and the Velvet Underground, Toronto artists had their own house bands: General Idea had the Dishes, CEAC, The Diodes. It was the moment, probably the only moment in Toronto, when the two scenes intersected; moreover, the music came out of the art scene. Crash ’n’ Burn, where punk broke in summer 1977 in Toronto, was in the basement of CEAC. Although eventually dropped in favour of new wave, punk nevertheless had an important role to play: punk’s demolition was instrumental in artists remaking themselves, transitioning from hippie sentimentality to new-wave irony.

THE MAGAZINE: What, for you, made Toronto’s art scene distinctive then?

MONK: I wrote the book partly as if the participants of the time were the revolving cast of a soap opera, with frequent name changes and gender switches. What was unique to Toronto was how artists participated in each other’s works, not only in the making of them – being the photographer, for instance, or video crew – but also in acting in others’ videos: David Buchan’s performance persona, La Monte del Monte, for instance, notably “guest” appeared in Colin Campbell’s video. This constantly circulating and reappearing cast of characters created a critical mass giving the effect of an established community, but in reality it was only reflecting the nascent community back to itself. This televisual “feedback,” in [Marshall] McLuhan’s hometown, was essential to the art scene establishing its identity.

In the book, I suggest that Toronto developed a unique form of conceptual art: camp conceptualism. This art was embodied and gendered, and dealt with codes and the transgressing of them. And it partook of what I call “Toronto talk.” Talk was Toronto’s theatricality: not only bar chatter and gossip, or the near slanderous polemics of the myriad artist-run magazines, but the pervasive language of the scene’s pop-cultural-oriented performance, video and wordy photo blowups that mimicked the strategies of advertising.

THE MAGAZINE: You lived through this era. What/who in Toronto were you seeing, following, experiencing and getting excited about?

MONK: I was an unusual critic in that I didn’t discriminate between uptown and downtown or between media, but wrote about everything: painting, sculpture, video, performance, text works etc. – whether of phenomenological or performative cast. You would think, given what most critics wrote about, that criticism was a nine-to-five job, dependent on galleries being open during the day, but the art world happens at night too, and you have to be part of it. The rhetorical structure of the book discloses what side of the performative-political divide I come down on. In the art scene, you may start out a formal phenomenologist, but don’t know how quickly you turn into a performative transgressive. My book revealed that to me.

THE MAGAZINE: If we can no longer have a true underground, what can we have? Or has the counterculture become over-the-counter culture?

MONK: The “underground” forms of contestation and conviviality I wrote about do seem to be of the past, but let’s hope that they have been transformed in ways that are not yet immediately visible or available to someone like me – the older generation.