The NFTease

by Deirdre Kelly

photography by Mike Ford

When, in March of last year, an NFT made international headlines after selling for nearly US$70 million at an online Christie’s auction, digital art suddenly became the least-understood thing everyone wanted to talk about.

Conversations typically began and ended with questions like “What is a non-fungible token anyway?” and “Who are these multi-millionaires (their identities concealed by video game–esque pseudonyms like MetaKovan and Twobadour) spending astronomical sums on what, to the uninitiated, looks to be as fleetingly faddish as a game of Candy Crush?”

The answers could be found easily on the web, where “nifties” (as the digital assets are colloquially known) have been proliferating over the past year. But with all the newfangled jargon that surrounds the burgeoning internet sensation, it still wasn’t easy to grasp what all the fuss is about.

NFTs represent a shift in how we view ownership and patronage in visual art

Telling someone that NFTs are non-interchangeable digital representations of artworks, sports cards and other collectibles that use certificates to verify ownership and authenticity didn’t help matters. Add in the fact that NFTs are sold in virtual marketplaces, using the same blockchain ledger technology as cryptocurrencies, and bewilderment only increased.

“NFTs represent a shift in how we view ownership and patronage in visual art,” says Tobias Williams (MFA ’13), a Toronto artist and academic who has minted his own NFTs on the artist-oriented Foundation platform. “We won’t really know the long-term impact of the phenomenon for years to come.”

NFTs are not just unfamiliar – they’re also intangible, so (to borrow a phrase from Gertrude Stein) it’s like there’s no there there. The payback is largely speculative, driven more by the siren-call of rarity than anything else.

Yet NFTs are a real thing, as evidenced by the huge impact they are having on culture, the economy and people’s buying and collecting habits. While quite literally a flash on the screen, subject to disappearance should the technology ever falter, they’ve captured the public’s imagination. They’re happening. Crypto speculators have taken to NFTs en masse, collectively spending close to a trillion dollars this past year alone on a bet that the assets will increase in value. The market is volatile, however, much like cryptocurrency itself. Prices have already dropped 70 per cent since U.S. graphic designer Beeple (a.k.a. Mike Winkelmann) sold his digital mosaic Everydays: The First 5000 Days for a record-setting US$69.3 million in March of last year.

Says Andrew Remington Bailey (MA ’17), a PhD candidate in York’s Visual Art & Art History department who is writing his dissertation on video game art with a section devoted to digital assets, “NFT prices have already had a tremendous number of ups and downs, which I think reflects their status as a trend in many people’s eyes.” But demand is far from over.

With eBay now allowing sales of NFTs on its platform, and even legacy-media stalwart Time magazine releasing a March 2022 issue as an NFT, digital assets are going mainstream, attracting people of even modest means who want in on the trading frenzy. For these, let’s say, average buyers, NFTs aren’t esoteric. They’re an updated version of an old-time phenomenon.

An NFT is a digital version of a collectible, not much different from the baseball cards I used to trade as a kid

“Basically, an NFT is a digital version of a collectible, not much different from the baseball cards I used to trade as a kid,” declares Henry Kim, director of the Blockchain.Lab at the Schulich School of Business. “What’s novel is the technology. Using the blockchain, you can always prove the authenticity of the certificate of ownership. The collectible and the certificate are basically the same thing. It’s an efficient way to collect.”

Certainly, it’s a craze gone crazy.

The Toronto Star reported in March of 2021 on 21-year-old Alberta art student Jonathan Wolfe, who struck it rich when he auctioned off one of his digital paintings, Living in my Head, for 24.43 units of Ethereum, the equivalent of US$55,555.55.

That’s a drop in the bucket compared to the prices paid for CryptoPunks, a randomly generated set of 10,000 rare digital characters that routinely sell for more than a million each. The highest paid for a CryptoPunk so far is US$7.5 million, a record price for a non-art NFT collectible.

Given the heaps of money involved, York University marketing professor Russell Belk, a leading expert on consumer spending habits, views the assets as a digital-era luxury good. It’s an “alternative status system,” as he calls it, and it has been developing ever since Vancouver-based venture studio Dapper Labs launched CryptoKitties, a popular online trading game, on the Ethereum platform in 2017.

Considered the original NFTs, the digital cats have since birthed an ever-expanding litter of digital assets in the form of GIFs, audio files, virtual real estate and tweets – like the one Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey sold last year at a digital memorabilia auction for an astonishing US$2.5 million.

The fact that the NFT market remains shrouded in secrecy (anonymity remains a major part of its appeal) has raised a few eyebrows as well. As reported in Nature, 10 per cent of NFT traders conduct 85 per cent of all transactions – a figure which suggests that, rather than the end of gatekeeping in media, NFTs have simply relocated it to a new forum. That’s not to mention the possibility of even more nefarious activities: thanks to sellers’ anonymity, there’s speculation that NFT sales are being used to launder black-market money, exchanging ill-begotten cryptocurrency for spendable USD under the guise of large (or numerous) sales of jpegs, memes and tweets.

Things can get messy by the fact that NFT sellers may not be the holders of the underlying rights of the works they are selling

But what does it mean to “own” a tweet? Pina D’Agostino (BA ’96, LLB ’99), a Canadian law professor and lawyer who teaches intellectual property law at Osgoode Hall Law School, asks an important question.

While a buyer might “own” the only screenshot of a tweet minted on a blockchain and digitally signed by its creator, anyone with access to the seller’s Twitter account can view, retweet or screenshot the tweet themselves. As the purchaser of an NFT, she says, your rights are, in fact, quite limited:

“Unless there is an explicit agreement to the contrary, the original creator retains the exclusive intellectual property rights, and therefore the rights to reproduce, display or make copies of the work. Things can get messy by the fact that NFT sellers may not be the holders of the underlying rights of the works they are selling. Examples include the sale of basketball highlights, where the underlying rights belong to the NBA, and Emily Ratajkowski’s sale of an image of herself standing in front of a piece of artwork she owns but may not hold the underlying copyright to.”

But despite the lack of regulations, more people than ever are buying into NFTs, motivated by FOMO, pent-up pandemic boredom or a firm belief that crypto goods are the way of the future.

In fact, art sales now account for a minority of NFT sales; the majority of sales, at least in terms of the number of transactions, are now connected to collectibles, gaming and the metaverse. It’s possible that, one day soon, it will be commonplace to reserve your unique outfit in multiplayer games like Fortnite or your personal avatar within Facebook’s digital world on the blockchain, ensuring nobody else can mimic your appearance.

Up until now, NFTs were only available to a super-savvy crypto crowd

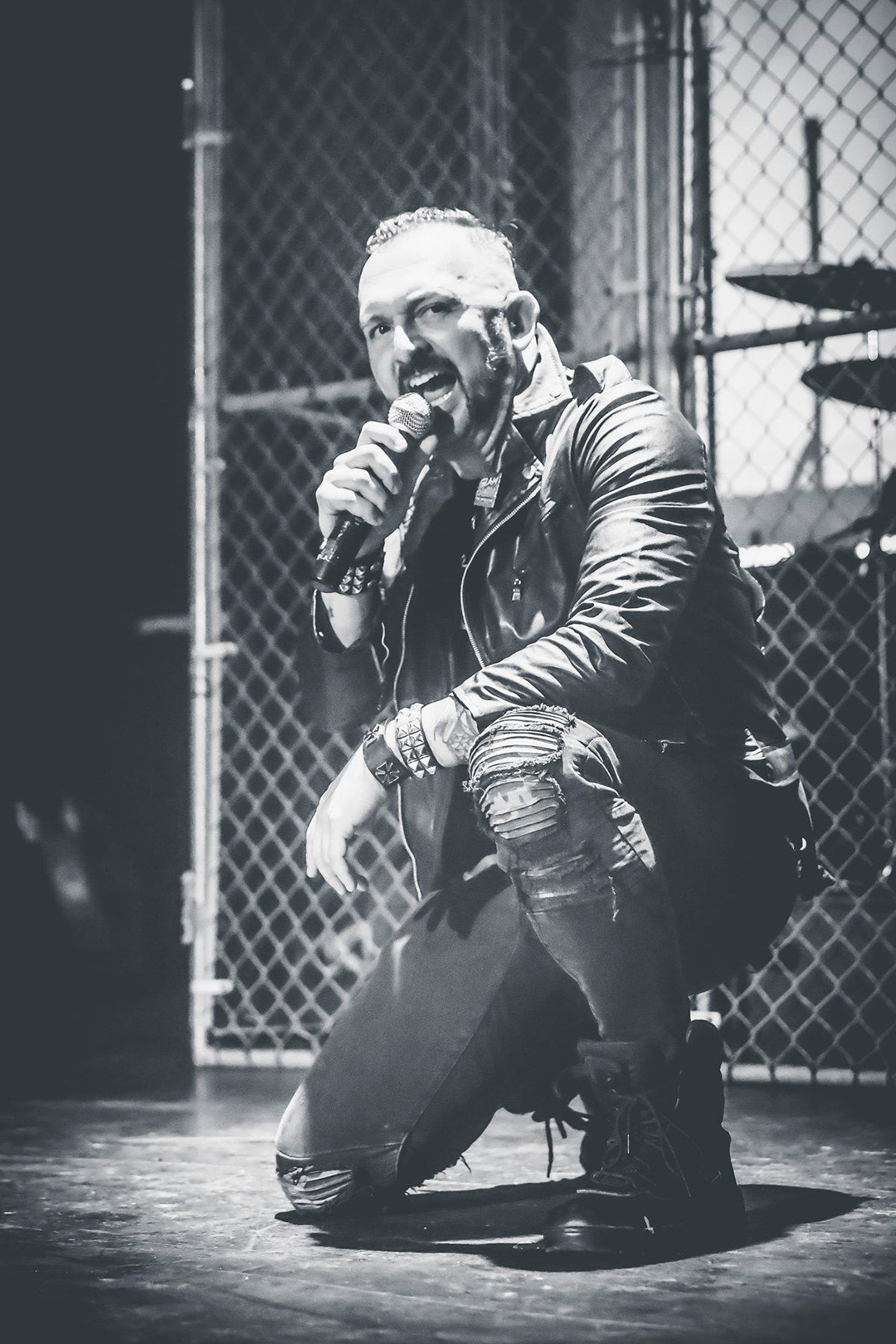

Even collectibles – which already accounted for 38 per cent of the NFT market by the end of 2020 – are destined to move to the blockchain. At least, Stevan Cvjetkovich believes so.

A non-graduated York alum better known as the masked pro wrestler Kobra Kai, the B.C. resident has launched LuchaCoins, billed as the world’s very first NFT digital trading cards inspired by lucha libre, a high-flying Mexican style of professional wrestling (and the kind he practises). Augmented by virtual reality, each asset depicts a gladiatorial warrior cast in bronze. Another series, called BlockChamps, is linked directly to a real-life wrestling star who has pledged to give a social media shout-out to anyone who purchases one of their licensed NFTs. With prices starting at $25, they appear as a unique, and wholly accessible, form of fan engagement.

“I’ve made a niche for myself in the market by being the very first wrestling sports trading card NFT set of all time,” says Cvjetkovich, who created LuchaCoins with special effects expert and fellow Vancouverite Angus Wakefield. “The reason that I became involved is because, up until now, NFTs were only available to a super-savvy crypto crowd.

“My mission statement, and the mission statement of LuchaCoins, is to make them accessible to fans so all people can engage with them. There is a huge market for large $6 million to $10 million sales in the NFT market, for sure. But most of us are working within a $50 to $1,000 price range.”

Artists can also use NFTs to engage directly with their followers, without the need for a third-party representative in the form of an art gallery or dealer. Of extra appeal to them is that many NFTs have a built-in feature granting the artist a percentage of any resale of the work, something unheard of in a regular art auction situation.

From this perspective, NFTs are a status-system disruptor; they are pushing the art world into new territory.

“I don’t think they are a replacement for the traditional gallery system by any means,” says Williams, the Toronto artist who has minted his own fine art NFTs, “but they could potentially be a way for artists, particularly artists working with digital media, to connect with their audience and generate some income, as well as the prestige that comes with selling their work.”

In fact, the digital transfer of currency may prove to be an ideal way for people to support their favourite artists, a modern take on the patronage of old. Fans can already contribute through sites like Patreon or by buying merchandise; in the future, unique or limited-edition NFT sales could enable artists and musicians to supplement their income while giving their supporters something special to hold onto – at least virtually – in return.

The massive blockchains and crypto mining companies minting the cryptocurrency used to purchase them do leave a massive carbon footprint

We’ve already begun to see what this could look like. In March of this year, notorious Russian performance group Pussy Riot raised $6.7 million for Ukraine’s war effort, and a slew of smaller transactions raised an additional $54 million, through the trade of NFTs. (A single CryptoPunk transferred directly to the Ukrainian government’s Ethereum account, for example, brought in over US$200,000.) While the funds raised are effectively donations, they’re transacted in a way that both streamlines the process of transferring money internationally and offers contributors something of value in return.

The same model could allow people around the world to raise money for worthy causes – to crowdsource funds for community projects, for example, or to further expand the micro-loan model already helping small-scale entrepreneurs to get their ideas off the ground from Bolivia to Malawi to Thailand. Whether you consider it an investment or a donation, buying NFTs can be a simple way to help contribute to worthy causes around the world.

What are the drawbacks? A biggie is that NFTs are incredibly energy-hungry, making them potentially hazardous to the environment. According to the Digiconomist website, a single Bitcoin transaction consumes more than 1,208 kWh, more than an average Canadian household uses in a year. The resulting carbon footprint is around 570 kilos, equivalent to 1,263,405 Visa transactions or 95,007 hours of watching YouTube. As a new consumer habit, the trade in NFTs is mightily wasteful.

Much of it isn’t to my taste and, arguably, not even what might be called contemporary art

“Although NFTs themselves are actually clean and do not cause much damage to the environment, the massive blockchains and crypto mining companies minting the cryptocurrency used to purchase them do leave a massive carbon footprint, and that’s worrying,” states Cvjetkovich, who, to mitigate some of the damage, used a carbon calculator to ensure his LuchaCoins produce less than a kilogram of organic waste. As well, Cvjetkovich works with Ottawa-based Tree Canada to plant a tree for every NFT he creates. “This allows us to offset our carbon footprint a hundred times over,” he adds.

A lesser evil, but for some still a concern, is that NFTs, when presented as works of art, aren’t always aesthetically pleasing. One person’s Uncle Bernie’s Trillion Dollar Superteat (to name just one of the images in Beeple’s Everydays collage) is another person’s trash.

“A lot of the work I see when browsing the NFT marketplaces looks to me like Tumblr content redesigned for software engineers,” Williams shares. “There’s been a rather unseemly rush by some larger established artists and institutions looking to cash in on a wildly speculative market. Much of it isn’t to my taste and, arguably, not even what might be called contemporary art.”

On the other hand, he has also seen creators whose work he does admire succeed on the NFT market. They include such established mid-career Toronto artists as Jonathan Monaghan and Rafaël Rozendaal, as well as emerging ones like Trudy Elmore and Malik McKoy. These fellow creators give Williams hope that something good might actually come out of NFTs after all. The future is uncertain, Williams says, “but I’m optimistic that NFTs will represent a new way to support and nurture artists who might not fit the traditional art world models.”

In other words, it’s early days. NFTs are still in their infancy. The digital space they occupy is fluid and continually evolving. Who knows yet what the future may bring? If there’s an NFT bubble, as some have warned, it hasn’t popped. Not yet, anyway.

“If the crypto market doesn’t recover quickly enough, high-priced NFTs may never come back,” says Kim, “but I do still think there will be a market for relatively inexpensive NFTs like baseball cards or Instagram influencer cards.” ■

With files from David Agnew