One is the Loneliest Number

by Alanna Mitchell

photography by Chris Robinson

As the COVID-19 crisis takes hold and people all over the world practise social distancing in a desperate attempt to stop the pathogen’s spread, loneliness has emerged as a common side effect of the coronavirus pandemic. Self-isolation has exacerbated feelings of vulnerability in all of us, but perhaps most of all in those who live alone.

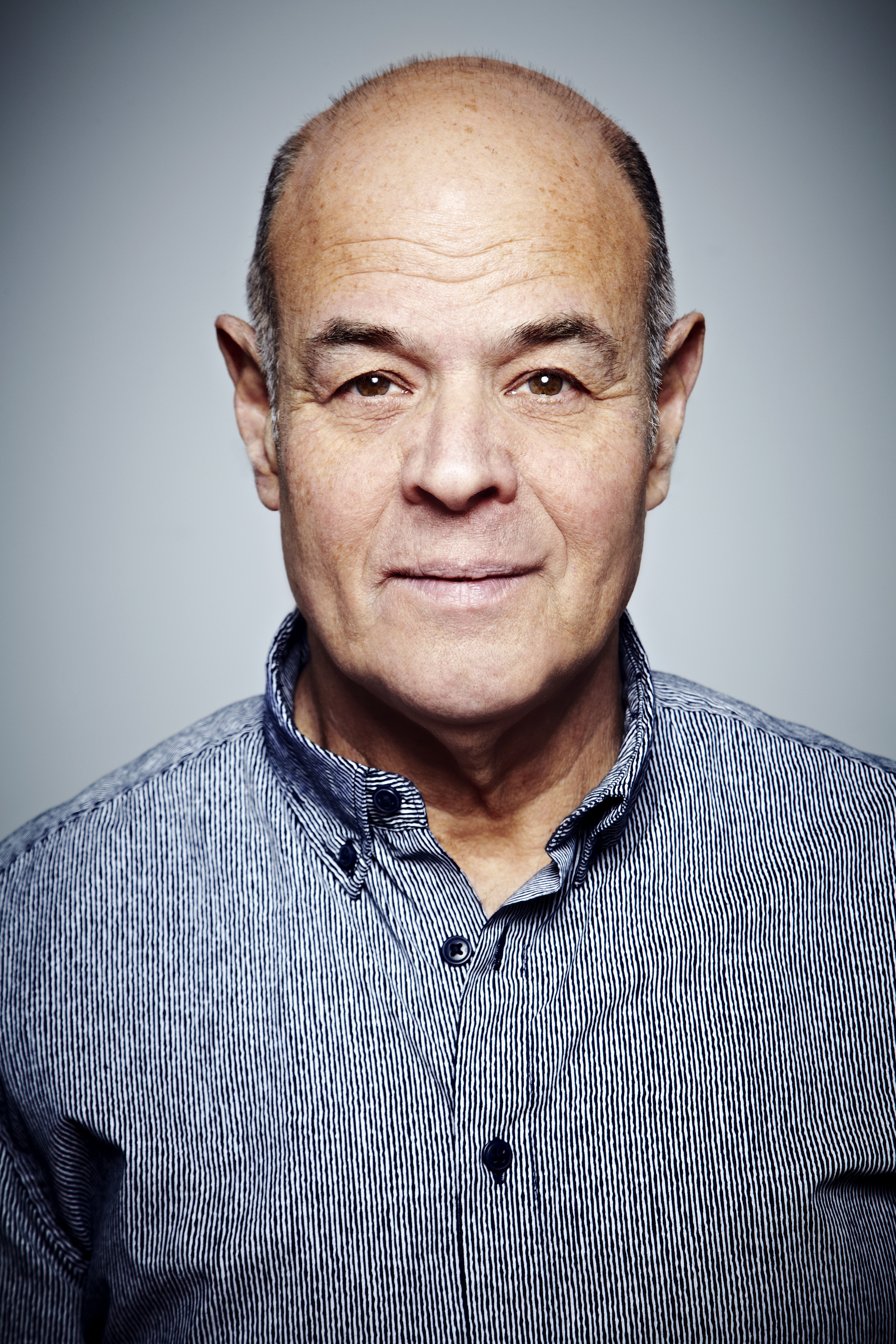

But if there’s one person who’s able to spot the silver lining, it’s Ami Rokach, a clinical psychologist at York University.

“It is good to sometimes be starved for others’ company,” he says from his home in Toronto. “We can come out of this experience with a resolution to be kinder and more welcoming to others – to enhance rather than neglect relationships.”

Forced isolation is a blessing in disguise – if a difficult one – that gives us the chance to remember that we are fundamentally social creatures, he says. Western culture cruelly misleads us when it tells us that we must take care of ourselves first.

“When we are in trouble, anxious and confused, the ones to help us through it are people in our social support network,” he says.

One of the world’s leading researchers on loneliness, Rokach has studied humanity’s “ancient nemesis,” as he calls it, for nearly four decades now. He says the opportunity for people to examine it more broadly began to emerge even before the pandemic.

“Loneliness has been hidden for too long, and now we’re starting to talk about it,” he says.

Here’s what he’s discovered. Loneliness is complicated, and it can feel overwhelming. Sometimes, it’s short-lived. Other times, it goes on for years. Sometimes loneliness is triggered by an event like the death of someone close to you, or by moving to a new city or country, or by a quarantine.

But sometimes there isn’t a tangible reason, leading Rokach to call loneliness an “essential” part of the human condition. No matter what wonderful things happen to you in life, that lonely feeling does not go away, perhaps the result of how you were raised.

The late John Cacioppo, a psychologist at the University of Chicago and another seminal researcher on the topic, discovered that loneliness can be inherited and that it is contagious. It can also have dire consequences over time.

Loneliness, research reveals, can lead to depression, anxiety, high blood pressure, dementia in the elderly and even early death, says Rokach, whose latest book, The Psychological Journey To and From Loneliness, published by Academic Press, came out last year.

Like pain, it indicates that something is not right, and you need to deal with it

The effects can be so devastating that the British government has labelled loneliness one of the nation’s biggest public health challenges. In 2018, Theresa May, then Britain’s prime minister, appointed a Minister for Loneliness while her government established a loneliness strategy to help citizens cope.

In Canada, the move prompted calls for a similar focus on loneliness, driven in part by alarm over findings from the most recent census, which shows that the number of adults living alone in this country has more than doubled over the past 35 years, reaching 4 million in 2016.

Wherever it comes from, loneliness is painful. It makes you feel that you don’t belong, that you’re not connected, that people don’t care for you or love you, that you’re unimportant. And it’s quite distinct from depression, which is a repudiation of others, or from solitude, which can be a refreshing interlude from human connection.

In all that feeling of helplessness and not knowing how to come out of that bleak place, we’re discovering new inner resources

But the pain of being lonely is a normal human emotion. It has a purpose, evolutionarily speaking. “Like pain, it indicates that something is not right, and you need to deal with it,” Rokach says.

In fact, his groundbreaking research has found that, for some sufferers, loneliness is a path to epiphany.

“In all that feeling of helplessness, and not knowing how to come out of that bleak place, we’re discovering new inner resources,” Rokach explains. “We start to appreciate other people and relationships. We are understanding that we can go through it and come out of there, and even grow from that experience.”

But how to get there? It starts with naming the problem and accepting that loneliness exists. After that, the key is to understand why you are lonely. Is it bred in the bone, or the result of loss or change or, hopefully, temporary social distancing?

For some, the answer might be found in therapy. For others, it’s in learning how to move away from thinking about yourself all the time. That could mean volunteering to help others or even joining a group of like-minded individuals where you can build friendships.

Despite his decades of research, even Rokach still feels lonely every now and again. “When it happens, one of the things I do, which I also tell my private patients, is to face it, not to run away and say, ‘No! I will jump into more work,’” he says. “If I’m lonely, I admit it.”

He even has a few tips for those who might be struggling with the stress of social distancing right now. The key? Decide to do something about loneliness. He suggests reframing the imposed isolation in your own mind as solitude rather than loneliness. It’s a time for catching up on reading or getting close to people you care about, or even tackling organizational tasks that you never felt you had time for.

And if you can’t figure how to break the cycle of loneliness, ask for help. After all, many of us are now in the same boat. ■