Dancing on the Edge

by Deirdre Kelly

photography by mckenzie james

When the curtain opened on DanceWorks’ 40th anniversary presentation at Toronto’s Harbourfront Centre last November, York University threatened to steal the spotlight. The Department of Dance that Grant Strate, a charter member of the National Ballet of Canada, founded at the Keele campus in 1970 had nurtured most of the artists on the program that night, as well as the event itself. “It definitely was one of the incubators,” says DanceWorks curator Mimi Beck.

Her own link to York stretches back to 1976, when she first relocated from her native U.S. to participate in the department’s annual summer intensive. Even back then, York had a reputation for artistic exploration and innovation that went beyond Canada’s borders. Beck recalls a fertile period when the dance department occupied the vanguard of new artistic expression and contributed to the formation of a Canadian contemporary dance identity that DanceWorks, co-founded by a York grad, has consistently looked to celebrate.

They think dance is a tiny, isolated field, but with this training our dancers can do anything

“Where I was coming from,” says Beck, thinking back on the department’s formative years, “it was the end of the Vietnam War and we were doing performance events with political activism and an anti-establishment feeling built into them. That was a big theme in the 1970s, and while York wasn’t the only place in Toronto where some of these ideas were being explored – 15 Dance Lab and the Pavlychenko Studios also come to mind – it is where that spirit of experimentation has continued until today.”

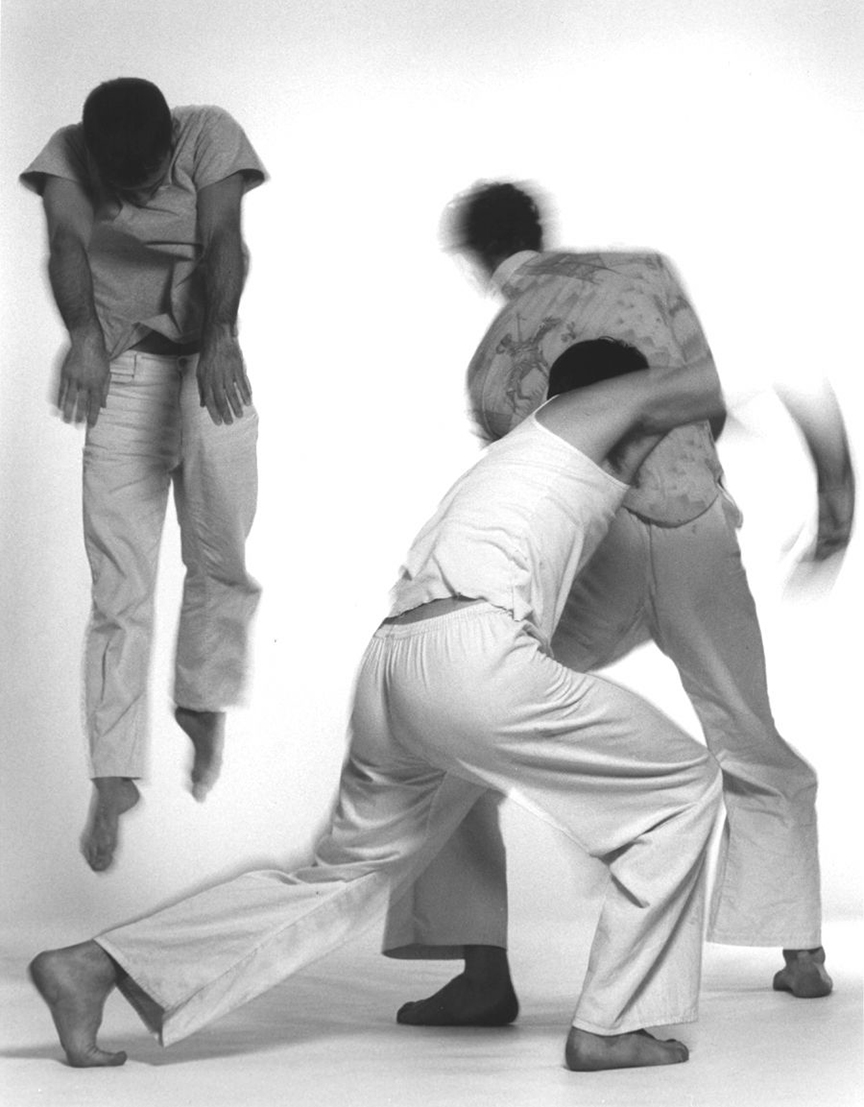

York’s past, present and future streams of influence flowed seamlessly together at the recent DanceWorks show, where former Toronto Dance Theatre dancer Learie McNichols and Toronto Independent Dance Enterprise (a.k.a. T.I.D.E.) co-founder Denise Fujiwara, both former York dance students, shared the stage with flamenco artist Esmeralda Enrique and Kathak performer Joanna de Souza, all presenting world premieres. For her part, Holly Small, another York dance alum, who went on to become a dance professor emerita at the University, contributed Cheap Sunglasses, a revival of a work she had originally presented through DanceWorks in 1981. Beck, who had remembered the work from the first time around, had asked Small to remount it for the anniversary show. More than 35 years later, it still packs a punch.

A dance that conceals and reveals the personality posing and pirouetting behind a pair of plastic shades, Cheap Sunglasses is set to composer Robert W. Stevenson’s virtuosic score for four vocalists combining a line from ZZ Top with the Fibonacci number sequence in mathematics for rhythmic complexity. Small created it for herself, originally, dancing it many times throughout the 1980s. But for this recent remount, she chose one of her students, Evan Winther, a tall and lanky Albertan in his final year of a BFA honours degree, to fill her enormous shoes. Born into a hockey family fourteen years after Cheap Sunglasses first saw the light of day, Winther initially learned the solo as part of an independent studies program that Small supervised at York in the fall. By the time he came to perform it for the capacity audience gathered for the Nov. 16 DanceWorks opening, he had mastered the sly ironies lurking beneath the surface of Small’s strut-and-swirl choreography. The house erupted with applause. A star was born.

“I felt a lasso on my body and a feeling of ecstasy on my face,” says Winther a few days later, during a lunch break in a student lounge, and referencing imagery suggested by Small during one of their many rehearsal periods. “It’s not just the movement,” he adds, raising his voice above the din, but choosing his words carefully. “It’s about discovering what makes the piece original, how it goes from one point to another. There’s always a logic to it.”

That logic extends to the dance department where rational inquiry is built into the study of artistically expressive movement. It’s one of the reasons why Winther crossed the Prairies to attend York, choosing it over Juilliard in New York. “I was surprised to discover how much research goes on at York and when I considered it I decided that this was the program I wanted to take,” he says. “A student in dance at York invests in his education outside the dance studio. And that ended up being a big attraction. Yes, we are doing dance five days a week. But there is also an academic side to the training that is very inspiring.”

Besides Small, Winther’s professors include the former indie artists Darcey Callison and Terrill Maguire, as well as the classically trained John Ottmann, a choreographer who has worked with ProArteDanza, the Royal Winnipeg Ballet and La La La Human Steps in Montreal. Regardless of their past achievements, teachers within the dance department take a collaborative approach in encouraging students to find their own voice as the next generation of dance artists. It’s an important distinction, and it traces back to Strate, a Mormon from Cardston, Alta., who established Canada’s first degree program in dance as the founding chair of the University’s Department of Dance. A master’s degree program followed six years later, another first for Canada.

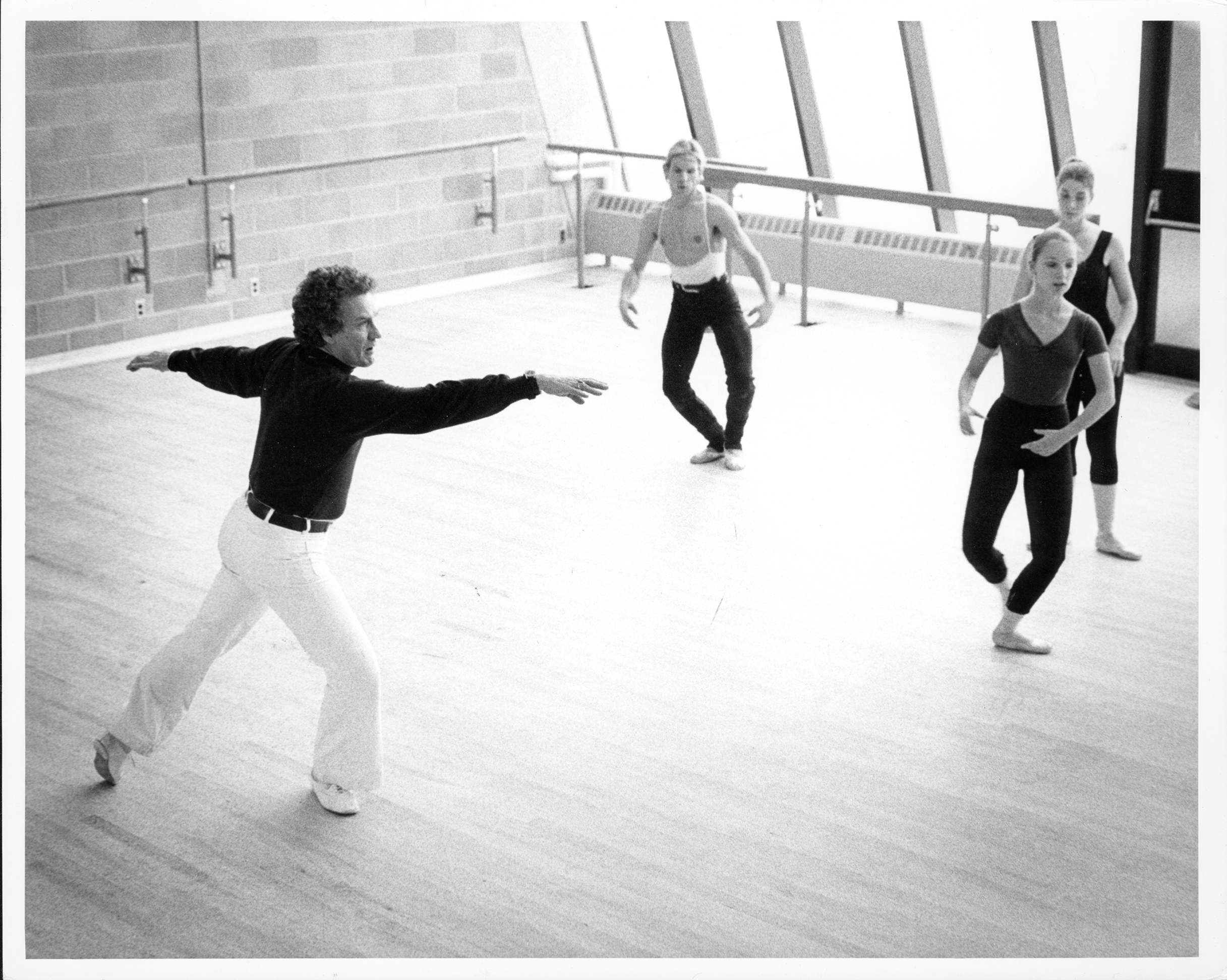

Strate had been a practising lawyer before turning to dance full-time in 1951 at the request of Celia Franca, then the National Ballet’s artistic director, who had seen some of the modern dance choreography he used to do on the side of his legal career. Strate was then 24, a relatively late age for beginning a life in dance. But his maturity made him approach the art form differently from his peers. What Strate might have lacked in technique he more than made up for in brain power. His early dance pieces, created for the National Ballet, evolved from a careful reading of literature and classical mythology. He wanted to go deeper, really change the way people studied dance in this country, and when he left the National in 1970 to come to York, his stated goal was the creation of “a thinking dancer,” one versed in letters as much as Limón technique, a style of modern dance. Strate’s brains-with-brawn methodolgy attracted the likes of Small, who thrilled to the idea of applying her intellect to the body in motion. “He was a visionary,” she says, sitting in her office on the third floor of York’s Accolade East Building. “His legacy here is remarkable.”

I auditioned one hot summer day for Grant Strate … and was so late I missed the official audition. I was completely distraught and mortified

Small’s own dance trajectory started in Kingston, Ont., where she was born 64 years ago, a descendant of dairy farmers on her mother’s side. Growing up she took ballet and tap, lessons that gave her a leg up, so to speak, when she became an Ottawa Rough Riders majorette performing at Grey Cup football games between the ages of 14 and 17. Her main goal was to become a writer. But while studying journalism at Carleton University she had an epiphany that would lead her into a full-time dance career. “I had enrolled in a women’s studies course and one day we learned about [modern dance pioneers] Martha Graham and Doris Humphrey, and suddenly it hit me that dancers could be artists. Beforehand I had thought of dance as an activity and as an entertainment,” Small says. “But that it could also be an art on some level convinced me to stop focusing on journalism. I realized I wasn’t cut out for it, anyway. I wasn’t tough enough.”

Shifting gears, Small looked to York to deepen her dance education. She arrived at the Keele campus in 1974, feeling lost and confused. “I auditioned one hot summer day for Grant Strate, took the interminable Keele bus up there in the sweltering weather and was so late I missed the official audition. I was completely distraught and mortified,” she recalls. “But Grant was so kind. He put me in Douglas Nielsen’s summer class and sat at the front and watched me and, based on that, he accepted me. I started the program that fall.”

At York, Small enrolled in the dance therapy program, another Strate initiative, that was then helping to put York University on the international map. Her teachers included the German-born Julianna Lau, an acclaimed dance therapist who had trained under legendary movement theorist Rudolf Laban in England after escaping Nazi Germany in the 1940s. The Julianna Lau Award in Dance Therapy, given annually to a graduate or undergraduate student studying or conducting research in dance therapy at York, recognizes her important contributions to what is today a growing discipline. “She exerted a powerful influence on so many of us studying with her in the ’70s,” Small says of her former teacher. “She didn’t care if we were crying, only that we gave her 100 per cent.”

A great many other world-class dance artists and pedagogues came to York during the Strate years, among them Frau Til Thiele (a former Bertolt Brecht associate), Robert Cohan (founding director of London Contemporary Dance Theatre in England), Antony Tudor (then choreographer-in-residence at American Ballet Theatre in New York) and Paul Taylor Dance Company dancer Danny Grossman (who loved York so much he relocated permanently to Toronto from Manhattan to start his own eponymous company). They were there to bolster Strate’s belief that dance was not only worthy of intellectual study but of great worth to society. Until his death in Vancouver in 2015, the Order of Canada recipient never stopped advocating for the art form. “People continually ask me what we are training all these young dancers for. They think dance is a tiny, isolated field,” said Strate in a 1971 interview. “But with this training our dancers can do anything.” And how.

Since its founding, the Department of Dance has produced an impressive roster of dance and other professionals. Graduates include DanceWorks co-founder and performance artist Johanna Householder, Cirque du Soleil and Madonna choreographer Debra Brown, Toronto Dance Theatre artistic director and choreographer Christopher House, DreamWalker Dance artistic director Andrea Nann and Dancemakers founders Marcy Radler and Andréa Ciel Smith, whose 1974 company, incubated at the dance department, consisted of York grads such as Carol Anderson (today a dance historian, writer and York professor) and later Julia Sasso (now artistic director of Dance Innovations, a choreographic showcase spotlighting new work by York faculty and students in their fourth year).

My instinct is not just repeating what’s been done. I want to push dance forward, and say something

Over the years, it has also produced its fair share of arts administrators, among them Assis Carreiro (a former artistic director of the Royal Ballet of Flanders and now a cultural strategist with the High Commission of Canada in London), Jennifer Watkins (who administers the Esmeralda Enrique Spanish Dance Company) and Catalina Fellay-Dunbar (currently the Toronto Arts Council’s dance officer). Given that the dance department has produced more than 1,625 graduates since its inception 48 years ago, the list does go on and on. “There’s always a York connection, not to put too broad a brush on it,” Beck says.

How will it now go forward?

“That’s always a question in my mind,” muses Beck as she prepares to launch the next DanceWorks season, likely with more York grads ready to take centre stage. “The youth will determine how it might advance.” Winther, for his part, already has.

“My instinct,” he says, “is not just repeating what’s been done before. I want to push dance forward, and say something original with my movement.”