How Jane Goodall Rocked Their World

by Joanna Thompson

photography by Gary Beechey

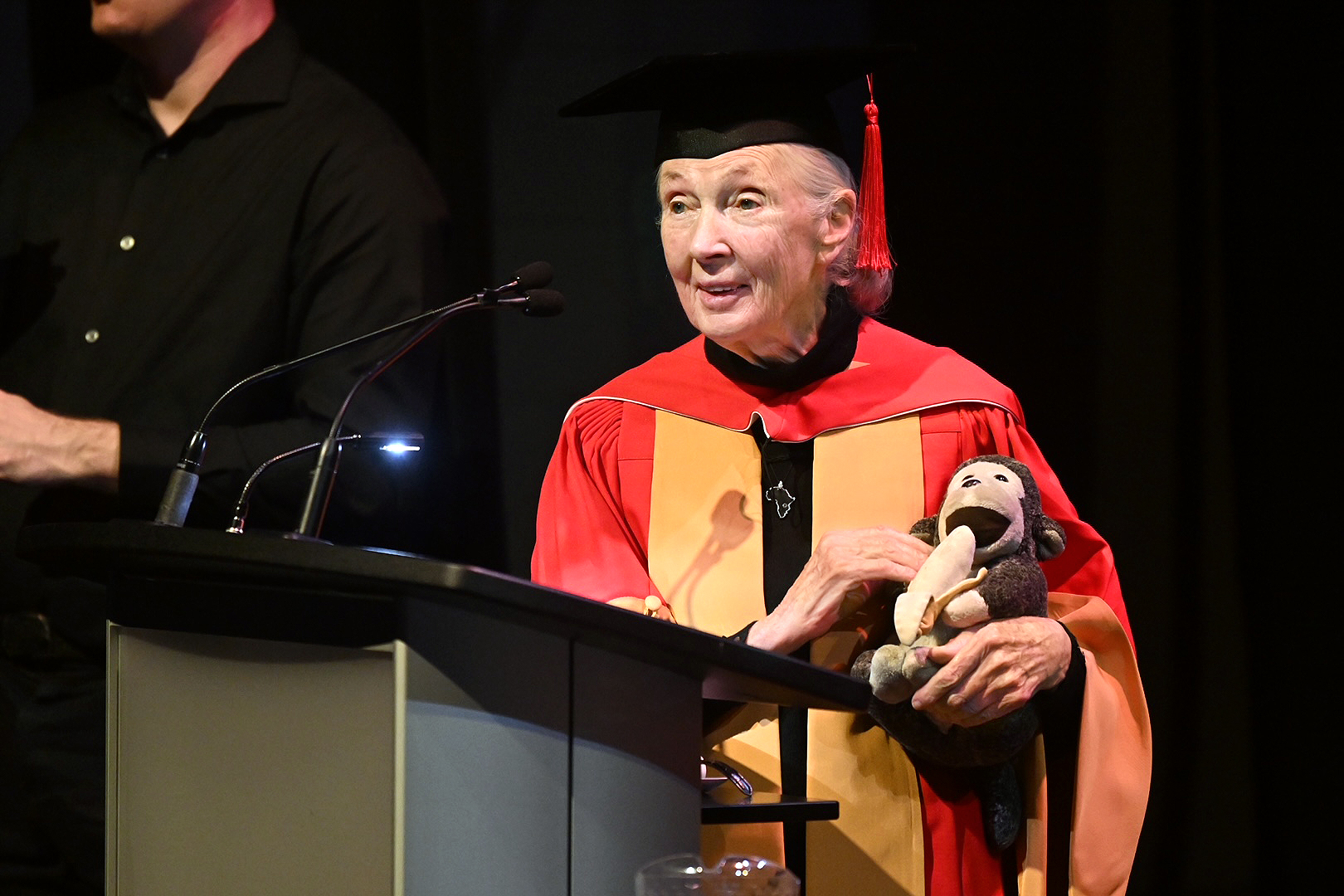

Jane Goodall stands tall among the giants of 20th-century science – a pioneer whose impact reverberates through the decades. From her groundbreaking studies on chimpanzee behaviour to her relentless advocacy for conservation, Goodall – who was recently awarded an honorary doctorate by York University – has shaped the course of scientific inquiry and environmental stewardship.

Now, at 90, her passion remains undiminished as she continues to criss-cross the globe, a tireless champion for our planet’s future.

Goodall’s influence extends far beyond academia, inspiring generations of researchers to follow in her footsteps. As the University prepared to celebrate her achievements at an April convocation ceremony held in downtown Toronto, professors Anne Russon, Valérie Schoof and Suzanne MacDonald reflected on the profound impact of her legacy and its enduring relevance.

FOR SUZANNE MACDONALD, Goodall’s influence began informing her worldview from an early age. “I started a conservation club when I was nine because I was like, ‘Jane Goodall is going to save the world,’” she recalls.

This initial seed blossomed into a career studying animal cognition. Her research has taken her from Canada to Kenya, studying primates both in captivity and the wild. And in the field of primatology, when it comes to Goodall’s impact on her, “I don’t think that I’m unusual in any way,” she says.

Countless other women in science can trace their origin story back to Goodall.

Like many areas of science, primatology began as a field largely dominated by men. Today, it is one of the few STEM disciplines where women outnumber men. This paradigm shift was, in part, sparked by role models such as Goodall and her contemporaries, including legendary orangutan researcher Birutė Galdikas and gorilla specialist Dian Fossey. “I don’t know if we would have been given the same opportunities, as women,” MacDonald says. “So she really did pave the way.”

I don’t know if we would have been given the same opportunities, as women. So she really did pave the way

Goodall began researching wild chimpanzees in Tanzania in 1960. Armed with only a notebook, pencil, binoculars and whistle for protection, the 26-year-old spent months carefully observing the apes’ daily lives. Her methods were, for the time, unorthodox. Rather than dryly assigning the chimps a number, Goodall gave them names and noted their individual personality quirks.

This unusual approach paid off. Over the course of her years of field work, Goodall became the first researcher to observe chimps using tools, building nightly nests and eating meat. Her success inspired other primatologists to take a similar track; today, many scientists employ a similar quiet, observational and holistic style of field work.

“When you just walk into the world of another species, you’re in a much better situation to understand them than if they’re locked up in a cell somewhere,” says Anne Russon, executive director of the Borneo Orangutan Society of Canada and primatologist at York’s Glendon Campus. “I think that’s probably what [Goodall] discovered herself.”

Russon, too, learned this lesson first-hand. She began venturing into the forests of Borneo in 1989, to study orangutan intelligence. Like Goodall, Russon carefully observed her subjects as individuals with their own preferences and personalities. Her research shed light on a huge range of great ape behaviours that were previously only attributed to humans, including the ability to pantomime. And though she no longer makes the gruelling journey to Borneo, she still recalls each orangutan she studied as vividly as the day they met.

Based on her experience, Russon believes that Goodall’s gender also likely informed her unique scientific perspective. Her smaller stature may have made the chimpanzees less fearful of her presence compared to the larger, louder men they had encountered previously. And viewing chimp behaviour through a female lens may have enabled her to interpret behaviour that her male counterparts missed, such as female reproductive strategies. “I think it very much changed the discussion,” says Valérie Schoof, a behavioural endocrinologist at York’s Glendon Campus.

Schoof encountered Goodall’s work later in life. “I wasn’t someone who was always enamoured with nature or anything like that,” she recalls. Schoof originally intended to go into mathematics, until an animal behaviour course at Queen’s University changed her mind. From there, she read several of Goodall’s books and fell in love with non-human primates.

I think about how brave she was to bring her family [to Tanzania] with her

Now, as a mother, Schoof relates to Goodall’s story in a whole new way. “I think about how brave she was to bring her family [to Tanzania] with her,” she says. In the 1960s and ’70s, women weren’t expected – or encouraged – to go on working after giving birth. But after her son, Hugo, arrived in 1967, Goodall continued her research while simultaneously adapting to life as a parent. It was a gutsy move.

According to Schoof, Goodall has helped push the field toward a more equitable future in other ways. Primatology has a long, ugly history of colonialism – particularly in Africa, where most great ape research takes place. White, Western researchers have a history of parachuting into marginalized regions only to collect what information they want, and then leaving without a second glance. In recent years, however, the discipline has been slowly reckoning with this exploitative past.

But throughout her career, Goodall has called for Western researchers to work together with Indigenous people in order to better understand local ecosystems. “She certainly has been an early advocate for the recognition that local people are critical to the conservation of nature,” Schoof says.

That work continues through several organizations, including the Jane Goodall Institute’s micro-grants for Indigenous youth, and Roots & Shoots, a conservation education program Goodall co-founded at the behest of 12 local teenagers in Tanzania in 1991. Today, Roots & Shoots works with passionate young people in more than 100 countries.

The future of conservation is more inclusive, diverse and co-operative than in the past. Which is good, because today’s young researchers and activists face unprecedented ecological challenges. Between the ongoing climate crisis, biodiversity loss, deforestation and rising sea levels, the next generation needs all hands on deck – and Jane Goodall’s legacy can provide a blueprint, inspiring them to push boundaries and seek new paradigms in their own work. “Without them,” Schoof says, “there is no hope.” ■