Telling Stories

by Alanna Mitchell

When COVID-19 hit, most of us ground to a halt. Not Dawn Bazely. Instead, the York University biologist and former director of its Institute for Research and Innovation in Sustainability leapt into action. Think human tornado.

She put all her own research to one side and launched herself fiercely into figuring out how to deliver course materials online. That was challenging enough. But what about a biology field course that a crop of locked-down students needed that first pandemic summer before they could graduate?

“So here I am inventing a virtual field course,” she tells me, laughing, over Zoom from her home in Toronto’s west end. “Here. Here’s a kit in a box. We’re going to send you a $3 origami microscope. We’re going to do frugal innovation. And we’re going to come online and do the field course in the indoor biome, your home, because none of you are allowed to leave your houses.”

A lot of people during the pandemic felt very isolated. I never felt more connected.

Hers was the only Canadian course of that type. She won the provincial minister of colleges and universities’ award of excellence for her efforts. But she didn’t just focus on students. Throughout the pandemic, Bazely poured time and energy into being a public science intellectual, explaining the science of virology, invasive species, vaccines, pandemic models and public health. She took square aim at disinformation, even explaining how to critically assess social media.

“A lot of people during the pandemic felt very isolated,” she says. “I never felt more connected.”

It was the culmination of more than three decades of work to make science more accessible and inclusive. For that sustained and innovative effort, Bazely was awarded the 2022 Sandford Fleming Medal for Excellence in Science Communication from the Royal Canadian Institute for Science.

Bazely is the 41st recipient, joining an illustrious roster of scientists, teachers and journalists. Among them: broadcaster and geneticist David Suzuki, journalists Jay Ingram, Bob McDonald, Eve Savory, Penny Park, André Picard and Ivan Semeniuk, and astronauts Chris Hadfield and Robert Thirsk.

During the online presentation of the medal in January 2023, Lt.-Gov. Elizabeth Dowdeswell, who is honorary vice-patron of the Royal Canadian Institute for Science, said that Bazely has “conceptualized knowledge as a nutrient connecting a person to global thinking.” She praised Bazely for nourishing generations of students and for equipping so many people to add to humanity’s store of knowledge.

Bazely, who has two science degrees from the University of Toronto and a doctorate from the University of Oxford, arrived at York in 1990. She’s been fearlessly charting her own path ever since.

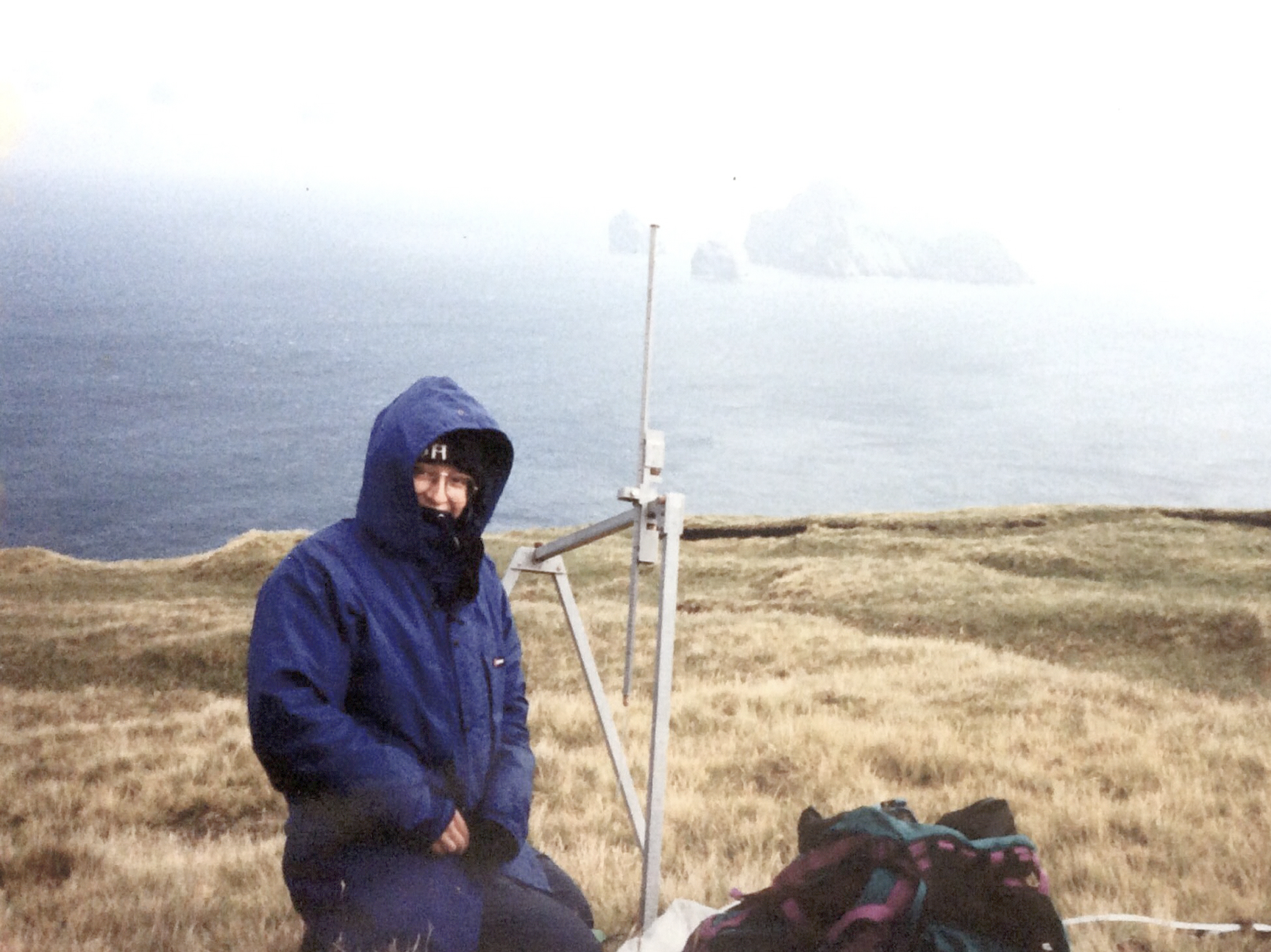

On one hand, she calls herself a “total lab rat” who loves the minutiae of experimentation and analysis. She also loves field work and spent some of her earliest research summers in the 1980s on Hudson Bay. But she refuses to be confined to either. She thrives on having multiple projects on the go. Everything interests her. She loathes being bored.

I like to say that ecology is the mother ship of everything, including economics, including engineering.

“I’ve taken a lot of time over the decades away from the ‘publish or perish’ treadmill,” she says. “And people have said to me, ‘Why are you doing those talks at the local library? You should be in the lab. You should be working on your latest paper.’”

The truth is that she refuses to see biology as a discrete discipline. By its nature, she says, it is radically interlaced with others. “I like to say that ecology is the mother ship of everything, including economics, including engineering.”

And including policy and politics. Bazely cut her public science teeth on the fraught issue of climate heating. She’s had physical threats from animal rights activists and aggression from climate change deniers. She has been a consistent champion for women in STEM, and for Indigenous Peoples. She’s made a campaign of including more women scientists in Wikipedia. She is unapologetic.

“There has been a narrowing down, I think deliberately, by various forces, who shall remain unnamed, of keeping scientists in their labs, in their trenches,” she says, “discouraging scientists from having a real policy impact or even, God forbid, a political impact.”

She’s by no means done. She jokes that she’s only halfway through her career now, at 62. Winning the Sandford Fleming medal is her cue to step away from the limelight, return to her many research projects, and take on yet another campaign: She wants to help York train other scientists to be comfortable speaking as public science experts.

“Let’s build the bench deeper and wider for scientists to be comfortable doing that,” she says. ■