Forward Focus

by Deirdre Kelly

photography by Mike Ford

Kaleb Dahlgren (BCOM ’21) has no memory of the crash that killed 16 members of the Humboldt Broncos junior hockey team and seriously injured 13 others, himself included, on April 6, 2018. When he woke up in a Saskatchewan hospital, all the then-20-year-old could think of was that he had an important game to play, and for some reason he wasn’t there. He wasn’t on the ice. Lying in bed, wrapped in bandages, he had no idea what had just happened to him: several brain bleeds, a fractured and punctured skull, broken vertebrae in his neck and back, muscle and ligament damage, blood clots and a large chunk of skin torn clean off the right side of his scalp.

His parents, who both work in the medical field, tried to console him, their only child, while they monitored his type 1 diabetes during the immediate recovery period. They knew the facts: that a transport truck had run a stop sign on Highway 335 and collided with the bus carrying the Broncos at full speed, with catastrophic results. The surrounding prairie fields were covered in twisted metal, peat moss, diesel and bodies so damaged that medical personnel on the scene would carry the trauma of what they witnessed that day for years to come. But his parents didn’t tell him that. Only that there had been a crash, a word they repeated because he could never remember what had happened. Not even two years later, when he started to write a book about it. “I thought that writing a book would tear open all the wounds for me. But it didn’t. It was cathartic, and I have zero triggers,” Dahlgren says with a pause. “I’m very grateful for that.”

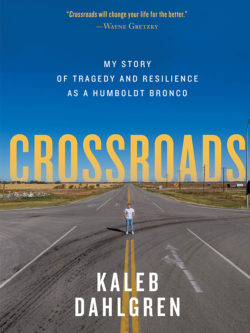

Released in March of 2021, just as he was completing an undergraduate degree at York University, Crossroads relives the day of the accident in minute detail: where people sat on the motor coach, what clothes they had on, what music was on the team playlist, the colour of the sky, the sound of the laughter, all the particulars Dahlgren could recall until everything turned black. Co-author Dan Robson helped to fill in the blanks from eyewitness and reported accounts. “A lot of research and hay went into filling in the blanks and trying to capture the enormity of the tragedy through a singular voice,” Robson says. “Interviews with Kaleb’s parents were particularly essential. Their voices are definitely in there.”

Dad took a photo of me surrounded by his hockey equipment. His skates, gloves, and helmet were about the same size as I was

The crash is the book’s turning point. But there’s more to the narrative than that. There’s the story of a Canadian hockey family whose devotion to the game, even before Dahlgren was born, exemplifies the significance of hockey in our national culture. There’s the story of juvenile diabetes, how from the age of four a young boy learned to manage it on the path to becoming an elite athlete. There’s also the story of rehabilitation and resilience, assisted by many caring individuals, including staff and faculty at York University. “Cheesy as this might sound, there were many crossroads in my life,” says Dahlgren, now 25. “The crash was just one of them. It does not define me.”

And yet the crash has scarred him for life. Dahlgren has a severe traumatic brain injury. Still. Doctors are amazed that he can even remember his name. His weeks are tightly organized around a treatment schedule of workouts for both the mind and the body, chiropractic adjustments, osteopathy, strict dietary measures, adequate sleep and more. It’s what Dahlgren in the book describes as “the grind,” and he’s learned to enjoy it. As a survivor of the crash, he feels duty-bound to his fallen teammates to live life to the fullest. Despite his doctors’ gravest doubts as to his ability to resume normal functioning, Dahlgren has taken charge of his own destiny. Not only did he skate again, but just months after the crash he moved to Toronto to begin classes as a full-time student at York University. “Had I listened to my doctors, I wouldn’t have ever left Saskatchewan. I would never have grown,” he says. “What I have learned from this whole experience is to trust yourself and give it your all, even when the odds are stacked against you. Remarkable things can happen.”

Dahlgren lived in residence when he arrived at the Keele campus in 2018. He had come to York as a member of the Lions Men’s Hockey Team. Though his medical team never cleared him for contact, he became a valued asset to the organization. During the three years he was with the Lions, Dahlgren served as the men’s hockey student council varsity rep, was involved in Lions leadership, and became a member of the Black and Indigenous Varsity Student Athlete Alliance, a recruiter, a social media director and an assistant strength and conditioning coach, among other positions. Coach Russ Herrington had selected him to join the team before the crash on the recommendation of Broncos assistant coach Mark Cross (BA ’16), an ex–varsity player who had taken a job as assistant coach of the Humboldt Broncos. Cross was on the bus that day and didn’t survive. He was 27.

“If Mark said we should look at someone, that was all the endorsement we needed,” says Herrington from his office at York University Athletics & Recreation. “Mark epitomized what we are always looking for,” Herrington continues. “Number one, a great human being; number two, a great student; and number three, an excellent hockey player. What we saw in Kaleb is that he certainly lived up to advance billing. He’s hard-working and loyal; he has a selfless nature. He strives to bring out the best version of himself every day, and if he’s living to his best version, he can inspire others to do the same. He’s an incredible role model.”

In person, Dahlgren radiates positivity. Dressed in jeans and a maroon long-sleeved henley T-shirt, with his hair fully grown back in, he’s fit, good-looking, polite and easy to talk to. His parents, psychiatric health professionals with experience in long-term care homes, raised him well. At home in Moose Jaw and, later, in Saskatoon, Mark and Anita Dahlgren were careful never to use negative words around him. They loved their boy dearly but didn’t coddle him. They taught him the value of hard work, along with humility and perseverance. They also taught him to love hockey. He didn’t have a choice, really. Soon after he was born on June 10, 1997, his hockey-smitten folks put a notice in the local paper announcing him as a future NHL draft pick. “They thanked everyone involved by giving them a position on the team,” Dahlgren writes in his book. “Dad was the coach, Mom was the general manager, the doctors were the assistant coaches, the nurses were the trainers, and the cheering fan club were my grandparents. A couple of months later, Dad took a photo of me surrounded by his hockey equipment. His skates, gloves, and helmet were about the same size as I was.”

Dahlgren was on the ice before he was out of diapers and in a league by the time he turned six. His favourite players growing up were Joe Sakic, Jarome Iginla and Jaromír Jágr. He quickly skated up the ladder, starting with “Timbits” hockey and advancing to Team Saskatchewan, a collection of the province’s best players in his age group. A strong forward with a flair for putting pucks into the net, Dahlgren eventually skated with the Humboldt Broncos, a Canadian Junior A hockey team whose name comes from the small Saskatchewan town where it was established in 1970, and rose to the position of assistant captain.

Right then and there, I said to myself, “I’m going to make a difference on a grand scale”

Throughout his playing career, Dahlgren had setbacks, whether it was his diabetes, his injuries or dealing with a curvature of his spine called Scheuermann’s hyperkyphosis. He had learned to manage his juvenile diabetes by watching his diet, monitoring his blood sugar levels, snacking regularly and getting plenty of physical activity. From a young age, he knew he had to control his disease or it would control him, and that’s just the way it would be. He has always been his own person. But the back problem was a different story. Nothing could ease the discomfort – not physiotherapy, acupuncture or massage. One day, as a last resort, he went to see a chiropractor. After one treatment, he found instant relief. He was 13. “That’s when I became fascinated, and I knew I wanted to be a chiropractor. I thought, ‘What a cool profession,’ and that I’d get to work with lots of athletes or others who suffered from pain. I knew I’d be happy doing that.”

His focus on that objective has been unwavering. At York, he took a commerce degree, confident that it would give him the business smarts needed to one day open his own chiropractic practice. He also studied human anatomy. “He had a knack for it,” says Nicolette Richardson, an associate professor in the School of Kinesiology & Health Science. “It’s a course not taken by science majors, and most students find it challenging. But Kaleb took it well. He was very organized. He completed the assignments early. Maybe that’s not super impressive to anyone not working with young people at a university, but that kind of foresight just isn’t common. He did really well and was a great student to work with.”

I just loved it because you’d hear different points of view from people from all over the world sitting right next to me. It was a next-level education

Dahlgren was a good student overall. He achieved high grades, was on the Dean’s List and named an Academic All Canadian every year by the time he convocated in the spring of 2021 – receiving several York Lions Varsity Athletics awards, including Outstanding Male Graduate of the Year, and giving a valedictory speech to his graduating class. Along the way, he took a volunteer coaching position with HEROS Hockey, served as national ambassador for JDRF Canada and continued his advocacy work with Dahlgren’s Diabeauties, a mentorship program for youth with type 1 diabetes, which he founded in Saskatchewan in 2017 (and which now has members across Canada).

After the crash, he emerged as a motivational speaker. His theme was finding positivity in adversity and cultivating a resilient mindset. He talked the talk and walked the walk. He was authentic. He struck a chord with people. “I gave my first speech in 2019, and almost right away I was getting messages saying that I should write a book. But I thought, ‘No way. I don’t have the time,’ ” he says. “And besides, what would my book be about? I healed. I didn’t think it was an important story that needed to be told.” But others continued to think differently.

Jeff Lohnes, the agent who books Dahlgren’s speaking engagements, started getting interest from publishers, so the opportunity to write a book was undeniable. Still, Dahlgren declined. He had his mind set on going to chiropractic college after graduating from York and wanted nothing to interfere with that plan. He was about to put an end to all discussions on the topic when something one of his York professors said made him suddenly change his mind. Walter Perchal, a lecturer in the School of Administrative Studies, had a habit of starting each class of Prospects and Parallels of Globalization with a pithy saying, something to jump-start a conversation among the students. “I just loved it,” says Dahlgren, “because you’d hear different points of view from people from all over the world sitting right next to me. It was a next-level education.” On this particular occasion, Perchal’s saying was this: “If you want to change the world, it starts with you.” He said it aloud to the class, but Dahlgren felt like he was talking directly to him. “Right then and there, I said to myself, ‘I’m going to make a difference on a grand scale. I’m going to write a book.’ It was a pivotal moment.”

Dahlgren immediately found himself in the enviable position of choosing the publisher he wanted to work with. Several had come offering him a contract, but he took his time in assessing which would be the best fit. “That’s when my commerce courses really came in handy,” he says, smiling broadly. “I knew how to ask the hard questions.” Ultimately, he selected HarperCollins Canada, a decision that came down to being able to tell his story his own way.

From the start, he knew he wanted to devote a portion of the book to the people that didn’t make it from the crash alive. He would use his own creativity when honouring them. Four and a half pages of the book are left blank to account for the loss of his memory of what happened that day and its aftermath. Chapter 16 is entirely a tribute chapter, a heartfelt dedication to the 16 who died. Dahlgren has also pledged the full proceeds from sales of the book to the STARS Air Ambulance to help pay for a new helicopter. So far, Dahlgren has donated $50,000 to that goal. He is hoping to raise another $50,000 by year’s end. He might just do it.

Crossroads was an instant success, quickly rising to the number one spot on national book lists. A paperback edition came out this spring. When it became a national bestseller last year, HarperCollins organized a Zoom call to celebrate the news. “I said that I didn’t need the acknowledgement, and that this was not important to me. You could see all their jaws drop,” he says, “but I meant it. What matters more to me than the title of ‘bestselling author’ is the DM I got from a man with cancer telling me that I inspired him. I did the book with the best intentions. I really do want to change the world. I want to make a positive impact.”

Today, Dahlgren is a full-time student in the four-year Doctor of Chiropractic program at the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College in Toronto. To give his studies his fullest attention, he officially retired from playing hockey last summer. The only way he connects with the game these days is as a fan. But he hasn’t put the skates away quite yet. In July, he will do a chiropractor job shadow with the Arizona Coyotes sports team in the U.S., followed by another job shadow in Galway, Ireland. He still has no memory of what happened on Highway 335 the day his world turned upside down. And that’s a good thing. For Dahlgren is not dwelling on the past. He is forging ahead, into the future. ■

Read More stories of York’s 2022 Top 30 Under 30!