Reboot

by Deirdre Kelly

photography by Mike Ford

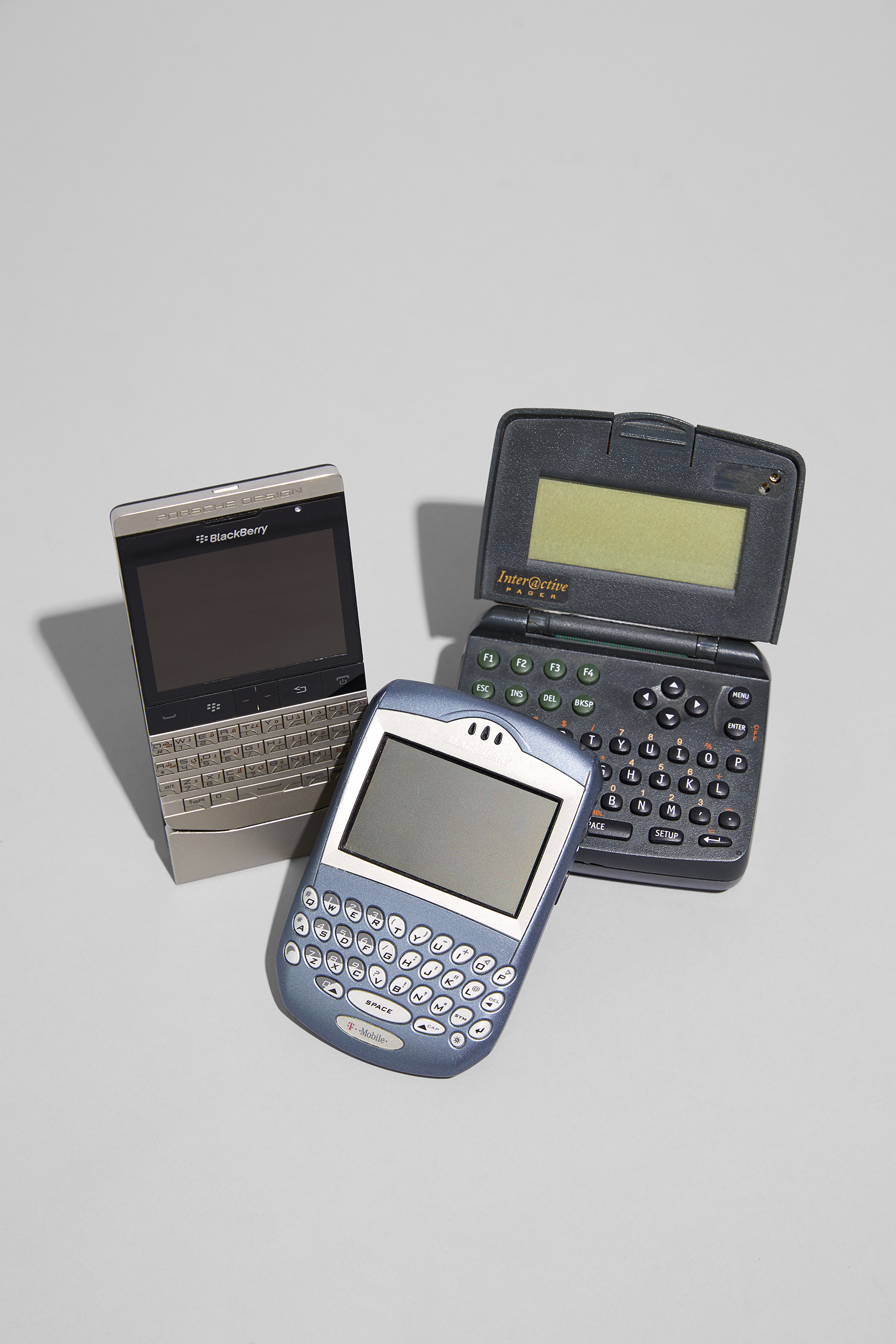

In 1974, a Ford Mustang convertible cost around $3,600 in Canada, while a personal computer – new to the marketplace – sold for $4,000, making it a comparable luxury item.

Flash forward more than 40 years, and today PCs have not only come down in price, they are ubiquitous, a staple of contemporary life.

It’s hard to imagine a time when digital technologies were a precious commodity, coveted by NASA and major research institutions like Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children, to name two early PC users, and mostly beyond the reach of the average citizen.

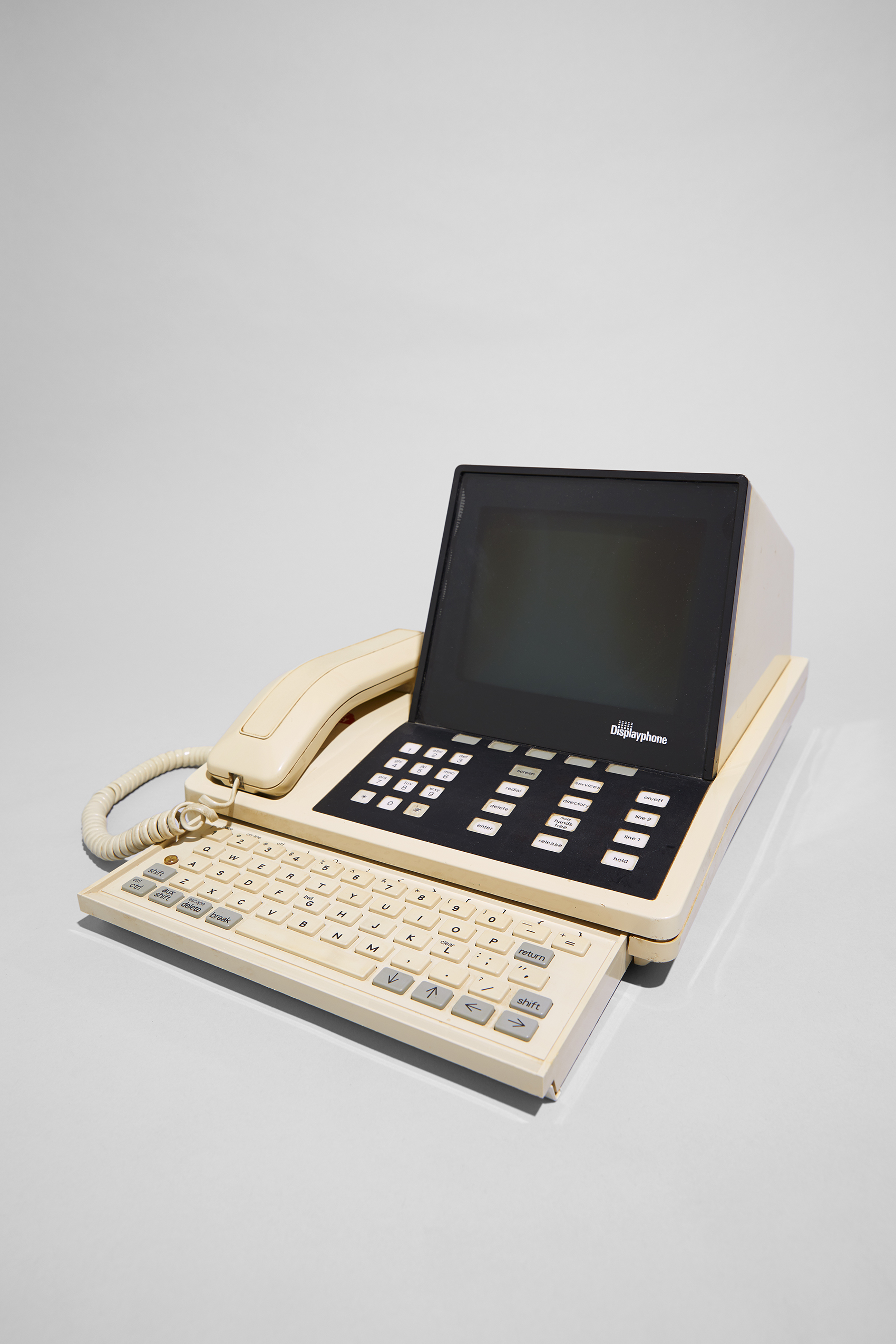

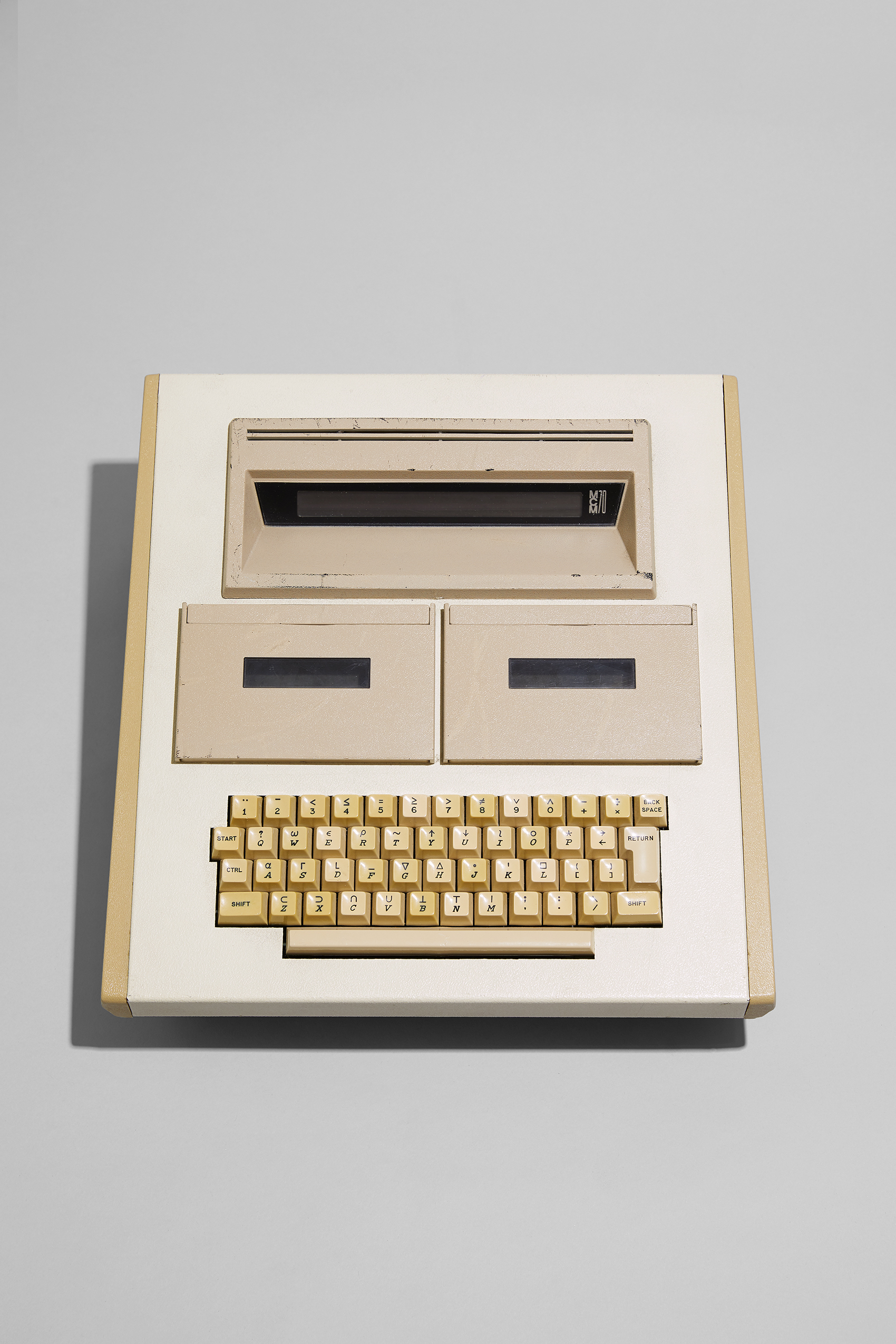

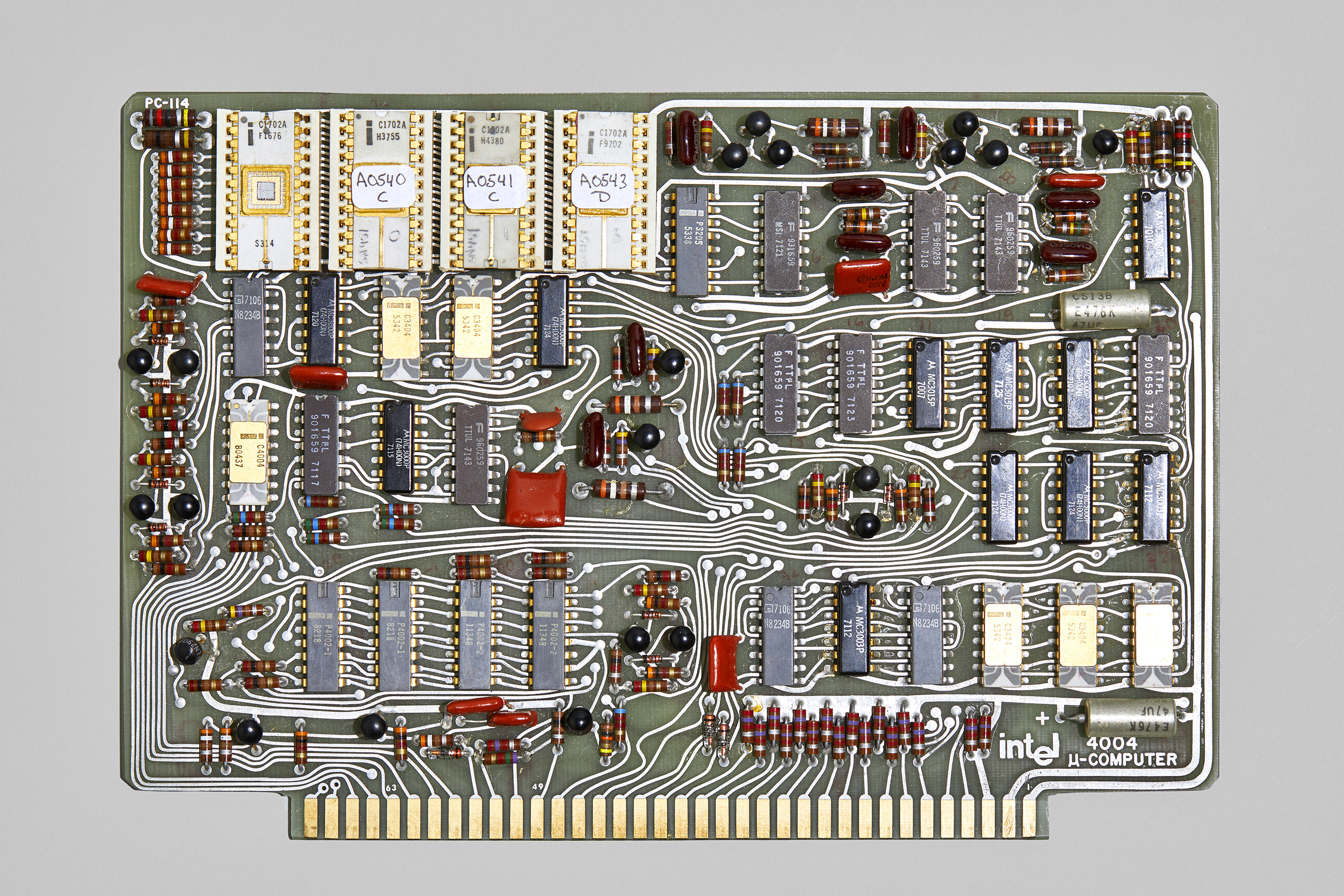

But going a long way to capture and recreate significant moments in Canada’s computing past is the bank-vault sized York University Computer Museum where, among other treasures, the world’s first personal computer – the Canadian MCM/70 – is housed.

“Our collection is the most comprehensive in Canada,” says Zbigniew Stachniak, a professor in the Lassonde School of Engineering’s Department of Electrical Engineering & Computer Science and a genuine PC enthusiast.

Founded in December 2002, the museum is Canada’s first and possibly largest single collection dedicated exclusively to the history of the Canadian computer industry.

The scope of the collection as well as the conducted research, publications and collaborations Stachniak has co-ordinated with several North American institutions has made the museum an internationally recognized archive.

“Many historically significant documents of the digital era are here.”

Artifacts the Polish-born academic has assembled since arriving at York in 1986 to teach computer science range from hardware and software to early storage devices, including core memory, floppy diskettes of various sizes and capacities. The collection also includes a 1917 Burroughs adding machine – manufactured in Windsor, Ont. – and a Wang 300 series programmable calculating system dating to 1967, and once extensively used by students and professors from York’s Faculty of Science.

There are also punch cards and tapes used with large mainframe computers such as the IBM 360 Model 30 that first arrived at York’s Keele Campus in 1965, heralding the coming of the digital age at the University. As well, IBM supplied the computers that York first installed more than 50 years ago to process paycheques.

Collecting is ongoing, a result of Stachniak actively soliciting his York colleagues to think of him when discarding their old computers and computer-related materials.

Building an academically significant research collection that would provide scholars, students, writers, artists, and the media with primary historical sources to research the development of computer technologies in Canada and their impact on Canadian society inspired the museum’s creation in the first place.

But not everything is about historical preservation and research. School visits and individual tours are common, as are encounters with the media. Vintage computer games and exhibits of early PCs with wooden enclosures and rows of blinking lights attract the most attention.

Stachniak keeps onlookers spellbound with hands-on demonstrations of old-time home entertainment and other early personal software on his reconstruction of the NABU Network – an early Ottawa-based personal computer system that Stachniak calls “the most innovative, daring, and least appreciated venture in the Canadian computer and communications industries.”

The only place in Canada where the NABU Network is now available, York’s Computer Museum frequently draws in former users looking to play Ski Sarajevo – an early NABU invention and a precursor to today’s video games – one more time.

“It’s like digital archeology,” Stachniak says. “A lot of social life is captured on these vintage storage devices.” ■