Alumni

Beyond Beatlemania

by Deirdre Kelly

photography by Horst Herget

Jerry Levitan (BA ’76, LLB ’79) is 71, and he’s still trying to explain something that happened more than five decades ago. We’re sitting in a quiet Toronto cafe. His hands are moving before his words come out, small, involuntary gestures, as if the story is impatient to escape.

“Every sinew of my body was electrified,” he says, then laughs, one part self-mockery, one part awe. “I know how that sounds. But I was 14. And there he was.”

Levitan is a lawyer, actor, children’s entertainer, Toronto Star columnist, Emmy winner and one of those rare people who can say he spent half an hour talking to John Lennon alone about world peace. He has been living, and reliving, that instant ever since. Not the version everyone knows: the book deal, the media appearances, the Oscar-nominated film. The real version: the moment you decide, from someplace so deep you can’t even name it, that you want to construct a life worthy of that kind of lightning strike. Or at least, not be solely defined by it.

It began, as Levitan says, with an obsession that would reshape everything. “Early on, I developed a passionate identification with John,” he reflects, settling back in his chair. “I could never have predicted where that passion would eventually take me.”

He was never an ordinary 14-year-old.

While other kids just screamed at Beatles concerts, Levitan was determined to actually meet one. Nursing a now lukewarm coffee, he proceeds to tell how.

Born and raised in Toronto, the son of a Holocaust survivor who worked in a kosher butcher shop at Bathurst and Eglinton, he had heard a rumour on CHUM radio that a Beatle and his wife had been spied at the airport, likely heading for the city. The self-declared Beatlemaniac then went into determined detective work, intent on finding the truth, along with his idol.

On the morning of May 26, 1969, he dialed up every downtown luxury hotel he could think of until the concierge at the stately King Edward hung up hard enough to give him hope. Changing into the purple double-breasted jacket he had worn to his sister’s wedding, a Brownie camera dangling from his neck, he skipped class at Dufferin Heights Middle School to jump on a bus from his home in north Toronto to the hotel’s King Street location.

Once there, he searched frantically floor by floor for where John and Yoko were staying en route to their Montreal bed-in for peace. He came close to getting caught by security when a kindly white-haired maid took pity on him and pointed him in the right direction. Knocking on the door of room 869 – the same suite where the Beatles themselves had stayed when they played Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens in ’64, ’65 and ’66 – Levitan invented “Canadian News” on the spot and let it unlock his destiny.

A contraband copy of Two Virgins – showing John and Yoko buck-naked on both front and back cover – in his hands, Levitan instantly captured Lennon’s eye. “How did you get that?” John asked in his Liverpudlian drawl. “I thought the Mounties had come in on horses and took them all away.”

After explaining how he had brazenly rescued a copy from the recall box at Sam the Record Man before police could confiscate it, John was duly impressed. He enthusiastically autographed a corner of Levitan’s coveted copy of the album, adding a whimsical line drawing of himself with Yoko – naked again. Yoko signed it, too. Years later, she would happily recall the moment: “I remember fondly, how young Jerry came to us and did the interview, when so many journalists were trying to speak to us. He was not only brave, but very clear and intelligent. Both John and I thought it was a very pleasant experience.” So pleasant, in fact, John insisted he come back for a second round.

Later that same day, armed with a reel-to-reel tape recorder he had begged, cajoled and ultimately received on loan from the astonished DJs at CHUM, Levitan returned to the King Eddie. Sitting inches from John, he queried him about the White Album, his fellow Beatles, his peace activism and his recent drug bust, which had made him persona non grata south of the border.

“Like a lot of people don’t want me in, you know; they think I’m gonna cause a violent revolution, which I’m not. And the others don’t want me in ’cause they don’t want me to cause peace either. War is big business, you know, and they like war ’cause it keeps them fat and happy and I’m anti-war so they’re trying to keep me out. But I’ll get in,” Lennon continued, “’cause they’ll have to own up in public that they’re against peace.”

After that life-altering meeting, the world felt restless in a new way. The tape came home with Levitan as proof. The voice of Lennon, patient, amused, philosophical, became a kind of haunting. It would stay with him the rest of his life.

But what next? He’d had a brush with fame – more than that, he had sat eyeball-to-eyeball with John Lennon, a freaking Beatle! He wanted that moment to mean something on a stage whose scale he couldn’t yet imagine. He knew he wasn’t going to be a rock star, but he thought of another way to create a sensation.

“I thought after that, I should go into journalism, because I scored probably one of the hottest interviews you could possibly get,” Levitan says. But he had another idol besides Lennon – a charismatic law professor-turned-politician-turned-prime minister named Pierre Elliott Trudeau. He asked himself, “Should I be a journalist? Or should I go into politics one day, like my hero?”

To answer that question, Levitan went to York University at a time when it was newly vibrant, conceived as an alternative institution that attracted draft dodgers, avant-garde artists and bold thinkers: politics in the cafeteria, protests clattering down the concrete hallways, professors who encouraged argument rather than obedience. For a young idealist who would brook no obstacles, York was a perfect fit, testing how far nerve and bold inquiry could take you. As an undergraduate, Levitan studied political science, then law at Osgoode Hall where he recalls performing in the annual mock trial and getting a D on his trust law exam. But that didn’t stop him.

Once he earned his degree, Levitan launched into a career as unconventional as his teenage exploits. He became a precedent-setting liquor licensing lawyer – Ontario’s go-to advocate in battles that blurred the line between culture and commerce. As Sir Jerry, he embraced the wild joys of children’s entertainment, creating full-band shows that made music for kids as serious as anything made for adults, while raising children of his own. He played small clubs and fancy halls. He walked TV sets (you can find him on reruns of The West Wing). He lectured on constitutional law. His boyhood crush became a lifelong love affair with risk, with creativity, with what it means to keep moving forward.

I thought after that, I should go into journalism, because I scored probably one of the hottest interviews you could possibly get

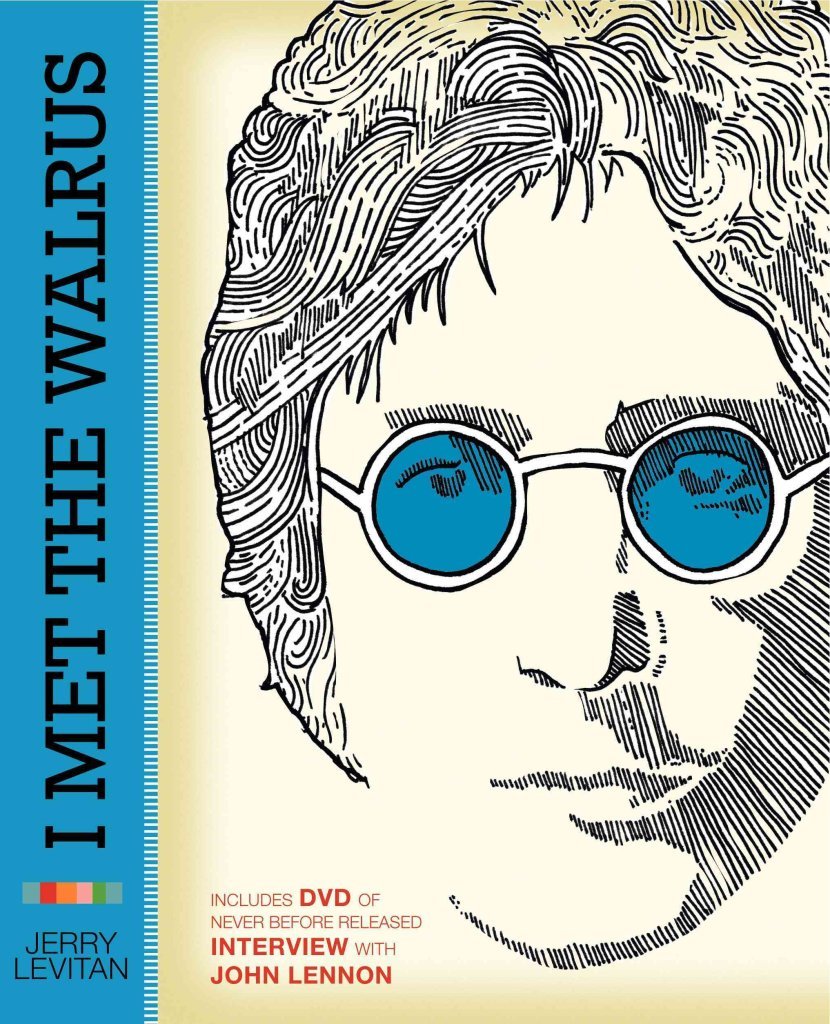

Decades after that first tape, Levitan found it again. The voices were unchanged, his and Lennon’s, twined together across the years. He wanted to share it with the world. Working with animator Josh Raskin (nephew of former Faculty of Education Dean Paul Axelrod) and illustrator James Braithwaite, he brought I Met the Walrus into being – a five-minute animated film that earned an Academy Award nomination in 2008, won a Daytime Emmy in 2009 and was selected for the inaugural YouTube Play Biennial at the Guggenheim Museum in 2010, letting a new generation listen in on their shared longing for a better world.

“Honestly, that’s one of my favourite interviews of dad, even without the animation, because it’s so candid and so relaxed, and it’s really clear that he’s in a certain mood because he’s speaking to you – and he’s speaking to a kid – so there’s nothing performative about it,” Sean Ono Lennon – John and Yoko’s only child – said in a subsequent interview. “He doesn’t feel like he’s trying to be Beatle John or deep thinker John or anything – it just seems like he’s talking to a kid and he sincerely wants to tell you things that are important and he’s doing it in such an unguarded way.”

In the pandemic, Levitan and Ono Lennon wove something entirely new: I Am the Egbert, a groundbreaking series of short films that trace one man’s journey from birth to death. Created for the 50th anniversary of Plastic Ono Band, the project pioneered a new use of Spotify Canvas technology, telling a complete narrative through short visual loops – the first time the medium had been used this way. Set against the raw emotions of Lennon’s 1970 album tracks and his chart-topping solo anthems “Instant Karma!” and “Give Peace a Chance,” each three- to eight-second loop stands alone while contributing to a larger story that mirrors the album’s emotional arc.

With such ongoing creative endeavours, Levitan remains plugged into what’s relevant in culture today. It’s why he is now an in-demand speaker, sought not out of nostalgia, but for his shrewd sense of how celebrity and politics intersect, and what can be done to shape a better future.

“I have a lot to contribute,” he says, not in the manner of a boast, but as a vow, his voice carrying just enough of that old teenage chutzpah to remind you that some doors, once opened, lead to others yet to be discovered. ■

— With files from John Lorinc