Bridging the Sound Gap

by MOIRA MacDONALD

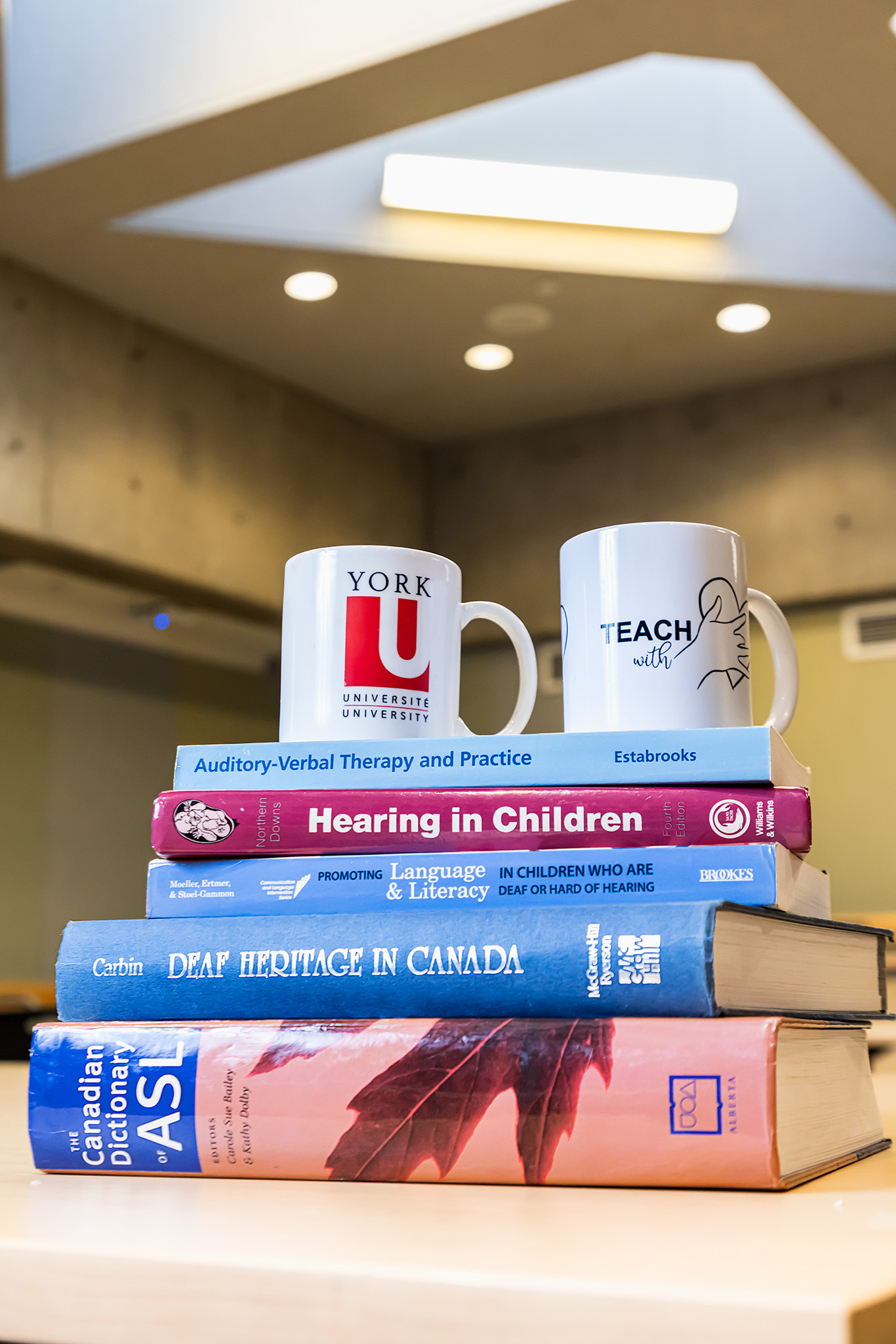

photography by Horst Herget

In the mid-1980s, when Pam Millett (PhD ’06) was an audiology student, hearing aids were the primary assistive devices available. These devices were larger than today’s models and had inferior sound quality compared to modern hearing aids. “That was pretty much all, because that’s the technology there was,” she recalls.

Nearly 40 years later, as a professor at York University’s Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing (DHH) Teacher Education Program, Millett guides teachers through a vastly different landscape. During an intensive week-long course that is part of the curriculum, these educators explore the multitude of technologies that have emerged since Millett’s student days, when American Sign Language (ASL) and Langue des signes québécoise (LSQ) were more commonly used as languages of instruction for deaf children in Canada.

While not technicians, York’s students must understand how these devices function – or might malfunction – to help their learners achieve educational milestones once thought unattainable. This shift was already underway as Millett completed her audiology training; within two years of her graduation, Ontario saw its first pediatric cochlear implant surgery.

Many of our deaf and hard-of-hearing students are just one dead battery away from not learning anything that day

Since then, cochlear implants have transformed the lives of countless deaf children by enabling them to hear. Though still imperfect, these electronic inner ear devices have steadily improved. They’ve been joined by other implantable devices, including nearly invisible Bluetooth-enabled hearing aids enhanced by artificial intelligence, and remote microphone systems that stream a teacher’s voice directly to a student’s hearing device.

“The technology is amazing and I never expected to see kids like this when I started,” Millett says. “But the thing that I say to our students every year is that many of our deaf and hard-of-hearing students are just one dead battery away from not learning anything that day.”

The York program prepares its students to address a wide range of challenges. These include practical issues such as replacing dead batteries or identifying when poor sound quality discourages hearing aid use. They also tackle more complex tasks such as supporting delayed literacy skills and ensuring signing children can continue learning through sign language. In addition to ASL and LSQ, Canada also recognizes Indigenous sign languages, reflecting the diversity of communication needs. Ultimately, the program emphasizes that the primary goal for these future educators is to maximize deaf and hard-of-hearing students’ access to classroom curricula and learning opportunities.

In Canada, approximately one to three out of every 1,000 children are born with hearing loss annually, a rate considered “low incidence.” This figure doesn’t account for hearing loss that develops later in childhood.

“We’re not trying to pretend that all these deaf kids have become hearing kids,” says Professor Connie Mayer, who, along with Millett, is a program academic coordinator. “We’re always saying to classroom teachers, ‘Be mindful … what they can hear is amazing, but they have to put more effort into the listening than the average Joe.’”

Established in 1991, York’s DHH Teacher Education Program continues a legacy of specialized teacher education that began in 1919 at the Sir James Whitney School for the Deaf in Belleville, Ont. This transfer of responsibility marked a significant shift in the preparation of DHH educators in Canada.

Building on this legacy, York’s program has grown to become the country’s largest of its kind, with approximately 50 students divided between a year-long, full-time option, and a three-year, part-time program. It is also one of only three such programs in the country, alongside those in British Columbia and Nova Scotia. As a result, most certified DHH teachers in Ontario graduate from York, where they earn a post-baccalaureate diploma.

To gain admission, students must already be certified teachers, hold a bachelor’s degree in education and have completed at least two sign language courses, although fluency is not required. York’s program structure has evolved in parallel with significant changes in deaf education.

As DHH teacher education transitioned to York, the educational landscape for deaf children was already shifting from primarily separate classes and schools to greater integration into mainstream classrooms, aided by advancements in hearing technology.

Today, most DHH students are taught in regular classes and York’s program is designed with this reality in mind. The program prepares graduates to work in a range of programs and settings, acknowledging that most will become itinerant specialists. These professionals will visit their students’ schools to provide focused support and collaborate with other educators involved in DHH students’ education.

As of 2021, Statistics Canada reported that only about 38,270 deaf Canadians (roughly 10 per cent) use ASL and LSQ. This decline in sign language use has led to less frequent use among teachers as well. While York’s program has never taught sign language itself, every cohort still includes fluent signers and teachers who use sign as their primary language.

We can’t believe what we’re seeing in terms of what kids can hear and their spoken language

Congregated settings remain but, “it’s not the same job that it was,” says program course director and practicum facilitator Melanie Simpson (MEd ’13), a teacher of the deaf for more than 20 years, who is currently pursuing a PhD at York.

As important as understanding students’ hearing technologies is, language and literacy development for DHH students is a critical topic in the York program’s curriculum, and an area where DHH students are most at risk of falling behind. That risk has been mitigated by much earlier identification and intervention.

Ontario introduced universal newborn hearing screening in 2001, and implants can be done before a child turns one year old. “We can assume that many more of the children come to the table with closer to age-appropriate language development upon which they can build literacy,” says Mayer, a language and literacy specialist, who also taught deaf children for more than 20 years before coming to York. “So what we’re teaching tends to go further down the path of, ‘OK, how can we teach more complex vocabulary?’”

As a result, “we can’t believe what we’re seeing in terms of what kids can hear and their spoken language,” Mayer continues. “Kids who speak two languages who are profoundly deaf, who speak them fluently, who are in French immersion – that was never happening.”

Still, technology remains imperfect. Subtle sounds and frequencies can be lost, while the peripheral noises of a boisterous classroom, HVAC systems or even an open window can make hearing more challenging. DHH students expend significant cognitive effort filtering this cacophony of sounds, potentially missing casual conversations where incidental yet important information and words are shared. Their specialist teachers are vigilant about all these aspects, working to ensure students don’t miss crucial learning opportunities.

Heather Kessler, who completed York’s DHH Teacher Education Program in 2021, now serves as a DHH literacy curriculum leader at Toronto’s Northern Secondary School. She recalls a pivotal insight from Mayer: “Our students are like Swiss cheese. They will know things and they will have huge gaps in unpredictable ways.”

This analogy resonates with Kessler, who applies it broadly. “I think about that for all our students: What do you know? Where are the gaps? Where are they hiding?” For students with multiple disabilities, DHH teachers face the additional challenge of determining which exceptionality is impacting specific aspects of learning.

Kathleen O’Connor (BA ’93, BSW ’95), a York program graduate and elementary grade itinerant hearing specialist teacher at the York Region District School Board, notes a growing trend. She’s encountering more students, including newcomers from other countries or jurisdictions, who are identified late as having hearing loss. These students often face significant academic challenges and require intensive support to catch up with their peers.

“It’s a totally different situation than a child who is identified right away at birth,” O’Connor says, requiring more collaboration with family, teachers, community and health services to ensure the student gets the help they need.

There’s going to be new technology that you won’t understand or that you won’t recognize

York’s program simulates the technological environment DHH teachers will encounter in their future classrooms. All classes feature real-time captioning and ASL interpretation when needed. During in-person sessions, microphones are used to ensure clear audio transmission, mirroring the assistive listening devices commonly used in educational settings for DHH students.

However, this in-person scenario has become a rarity. Since the pandemic, the full-time program has transitioned entirely online, delivered synchronously. This shift has maintained the program’s commitment to accessibility, with virtual classes still featuring captioning and ASL interpretation. The online format has also extended access to teachers across Ontario and beyond, with the program now reaching educators in B.C. and Alberta. The part-time program, online since 2008, had already paved the way for this broader accessibility. For Ontario teachers, tuition is covered through provincial government funding.

This expanded reach is crucial for improving access to education for DHH students. The program’s small team frequently receives inquiries from school boards seeking qualified DHH teachers, reflecting an ongoing shortage of these specialists. Enrolment is partly constrained by the availability of practicum placements, which require both a sufficient number of DHH students and mentorship from qualified DHH teachers. “We’ve become really creative,” says Simpson. “There are willing retired volunteers if we need them. And we’ve also actually done some mentorship over Zoom.”

Despite advancements in hearing technology, the need for specialist support remains critical. School board administrators sometimes underestimate the importance of providing DHH specialist teachers, especially when DHH students appear to cope well in the classroom.

York’s program faculty work to educate boards that “the need hasn’t gone away; it’s just different,” as Mayer emphasizes. Graduates emerge equipped not only to teach, but also to advocate for their students and empower them to self-advocate – essential skills in ensuring DHH students receive appropriate support and access to education.

Back in the classroom, technology continues to advance rapidly. Kessler’s classrooms now feature live captioning for even casual conversations, thanks to a company called Streamer. Additionally, the development of assistive learning and literacy software, such as Google’s Read&Write, is once again transforming the educational landscape for DHH students. For teachers of DHH children, keeping up with these innovations is not just beneficial – it’s essential.

“There’s going to be new technology that you won’t understand or that you won’t recognize,” says Kessler. She emphasizes the responsibility that comes with the role: “It’s our job. We need to figure it out. We need to know what it is and how to use it best – because we are providing access.” ■