Bad Trip

by Rita Simonetta (BA ’99)

photography by Chris Robinson

Summertime is a boon for air travel as eager Canadians take to the skies, excited about their long-anticipated vacations. But it also brings back bad memories of last year’s air travel fiasco at Toronto’s Pearson International Airport: stranded passengers whose flights were delayed or cancelled slept on terminal floors, planes full of exhausted travellers sat on tarmacs for hours, frustrated holiday-goers aired grievances about insufficient and inept staff.

These problems and more were all duly noted and not just in Canada but around the world.

These problems and more were all duly noted and not just in Canada but around the world.

“Toronto Airport Is World’s Worst For Delays,” read a headline in the Wall Street Journal. “Toronto Pearson: ‘I just need to get out of this airport,’” declared another by the BBC. The troubles didn’t end there. Mountains of unclaimed luggage left over from the summer spilled into the airport’s hallways come winter. People waited days and even weeks to collect their belongings.

What caused the problem? It’s complicated.

“The air industry is an ecosystem,” says Steven Tufts (PhD ’03), a professor in the Faculty of Environmental and Urban Change who studies the geographies of work, workers and organized labour. As a complex network of many parts, when one part is stressed the whole structure is impacted. The pandemic was a particularly nasty stressor. It exacerbated problems that were already there, creating the scenes of chaos witnessed at the airport last summer.

Many of the problems besetting airports like Pearson, such as travel delays, could be eased with more technological know-how

As the world went into lockdown, air travel came to a screeching halt, becoming one of the industries hit hardest by COVID-19. Employees who were part of the multifaceted aviation network – from pilots to baggage handlers – were laid off en masse. An estimated 4,000 workers exited the sector within two years; some never returned.

Efforts were eventually made to replace staff once air travel resumed following the lifting of most pandemic-related restrictions. But it was too little, too late. “They couldn’t hire fast enough,” says Tufts, adding that the sector has ceased being regarded as a long-term employment option as a result of stressful working conditions, lacklustre benefits, long hours and low starting wages.

According to Transport Canada, the number of commercial pilot licences issued has plummeted by more than 80 per cent as of 2022.

The Canadian Council of Aviation and Aerospace says that more than 7,000 pilots will be required by 2025 to meet demand.

With a dwindling supply of pilots, flight delays and cancellations could turn into an everyday occurrence.

It’s made the industry rethink how to get people moving again at the airports.

Just before the 2023 spring break, the Greater Toronto Airports Authority (GTAA), which operates Pearson, imposed a set of regulations for peak travelling times. The organization had no intention of replaying the frenzy of 2022.

With a dwindling supply of pilots, flight delays and cancellations could turn into an everyday occurrence

The GTAA placed a limit on the number of international passengers arriving, and those departing to the U.S., through each terminal at any particular hour. The organization also set a cap on arriving and departing commercial flights.

“The GTAA has been working for months to make every aspect of airport operations better than last summer,” GTAA spokesperson Guy Nicholson says. “This work has been taking place across the airport, and not just by the GTAA. We work in collaboration with airlines and our agency partners, which also contribute significantly to operations running smoothly at the airport.”

Beginning last August, the GTAA revamped slot scheduling in collaboration with the airlines to smooth hourly peaks and fill in valleys of demand to make passenger throughput more efficient. It also brought in an outside firm to do a baggage-system health check and assessment, and stocked up on parts to avoid supply-chain issues. As well, it installed AI technology that monitors the turnaround work done by the airlines and their ground handlers and sends alerts to relevant stakeholders to reduce delays and optimize the time planes spend at their gates.

“We are also optimistic that provisions outlined in the [March] federal budget announcement will lead to more efficient security and border screening, plus better data sharing by the airlines, which should improve planning and staffing for everyone,” Nicholson says.

York economist Fred Lazar is an aviation industry expert who believes adding more technology at the airport is a good thing. Many of the problems besetting airports like Pearson, such as travel delays, could be eased with more technological know-how, something that the industry is sorely lacking.

“They just aren’t technologically savvy,” Lazar says.

And that has to change.

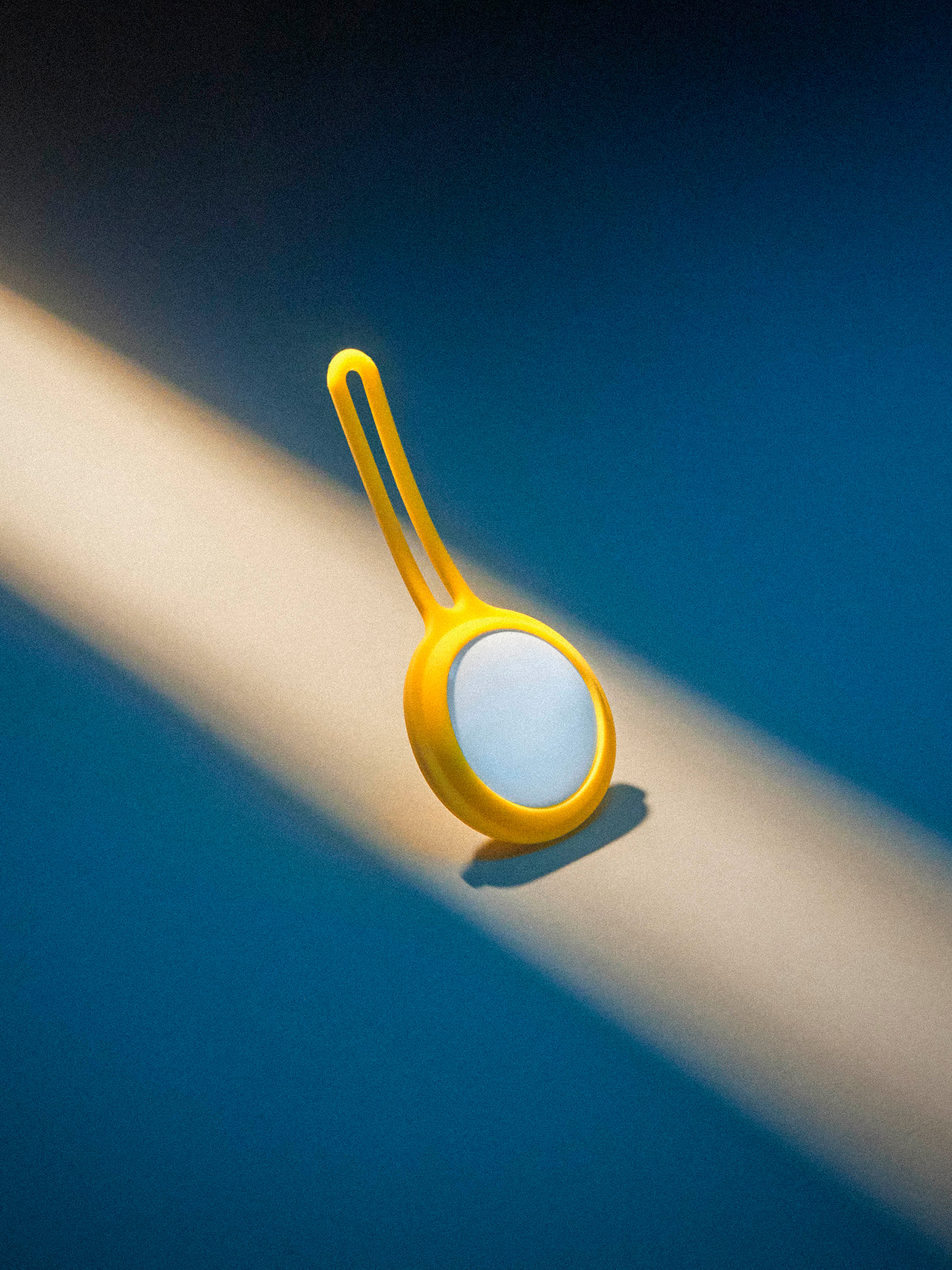

For instance, the current use of luggage barcode tags is time consuming. A more reliable and efficient option would be to equip baggage with chips. “You’ll know in real-time where that bag is,” Lazar says. “All you would need is a scanner.”

Lazar is also a supporter of contactless technologies, such as facial recognition, to usher in a new era of efficiency, arguing it would reduce the various security checks that slow down passenger flow.

But Tufts says that’s another complex issue: “These solutions take years to implement and require passenger know-how.”

A frequent traveller, Tufts illustrates the point with a recollection of an elderly couple who randomly sought him out to help them navigate the airport check-in kiosk. The learning curve will only become steeper with the introduction of even more advanced technology such as facial recognition. Also, he says, “these technologies are expensive and controversial.”

While the newcomers are a positive step in the spirit of competition, there simply isn’t a viable market to support them

Activists have long argued that in the wrong hands, these tools could be used as a means of surveillance and infringe on an individual’s democratic rights. Then there’s the worry over misidentification, as well as the possibility that the algorithms behind facial recognition – which ultimately learn from human experience – can reinforce gender, race and class bias and discrimination.

In the meantime, there are other matters to confront. A slew of budget airlines has entered the already crowded playing field. Flair and Lynx are a few of the new arrivals that have banked on cost-conscious consumers hunting for savings. These discount airlines can offer super-low base prices, since passengers have to pay out of pocket for things such as checked bags and snacks.

Workers may be tempted by available work at the budget carriers, but retention rates are low.

Experts say that while the newcomers are a positive step in the spirit of competition, there simply isn’t a viable market to support them for the long haul. In March, Flair had four of its aircraft seized, reportedly as a result of overdue payments.

Yet another looming issue is the growing shortage of pilots. The wave of pandemic-related retirements and layoffs, along with an aging workforce, has considerably reduced the pool of talent.

The GTAA says it’s aware of this issue and has taken steps to help airlines with the pilot shortage, including working on an airport-wide job portal. The organization points out that in January, 2,300 people registered for the job fair at Pearson.

But down on the ground there are other issues that need to be addressed, says Lazar, such as the need to increase security staffing levels and capacity.

“Most airports weren’t built for the levels of security that came into place after 9/11. Space allocated to it is insufficient for the dramatic increase of passengers we’ve had in the past 20 or so years.”

For Tufts, the way forward is a transformation when it comes to the individuals who are integral to the air travel ecosystem.

Responsibility isn’t solely with individual entities, such as the airlines, Pearson or even the GTTA, Tufts says. “What’s needed is a national aviation employment strategy,” he says, and that means the federal government has to roll up its sleeves and get involved.

A greater sense of involvement and integration is also needed from Toronto’s biggest airport, says Tufts. “The airport should be more than a hub, but part of the city.”

The GTAA is working on it.

“In terms of Pearson’s links to downtown Toronto, we are working with our partners at Metrolinx and all levels of government to continue the planned connection of the Eglinton Crosstown West Extension to Toronto Pearson,” the GTAA’s Nicholson says.

Tufts, who continues to advocate for living wages and a workers-centred airport (a grocery store and gym, along with other amenities for employees have been suggested), says that as it stands, the air travel industry is losing out on skilled talent.

Avoiding the travel mayhem Canadians experienced last year will require an overhaul at the most essential level. “We need to reinvest in people,” he says. ■