Alumni

Going Deep

by Daniel Oberhaus

At this point in her career, Jill Heinerth and death are on a first-name basis. After nearly three decades as a professional cave diver, Heinerth (BFA ’88) has been pinned beneath icebergs in Antarctica and incapacitated with the bends in the jungles of Mexico. Most people might take these experiences as signs that it’s time to change professions. But Heinerth accepts the risks of her calling with a hard-won stoicism forged by recovering the bodies of friends and strangers from the depths.

“When an emergency occurs, there’s suddenly a million conversations happening in your head all at once, and you just have to take a deep breath and turn off the emotions,” she says. “After the danger has passed, you have to make time to honour those emotions, recognizing that some of them might hang on for weeks or a lifetime. It reminds you that this thing you’re involved in is truly life and death.”

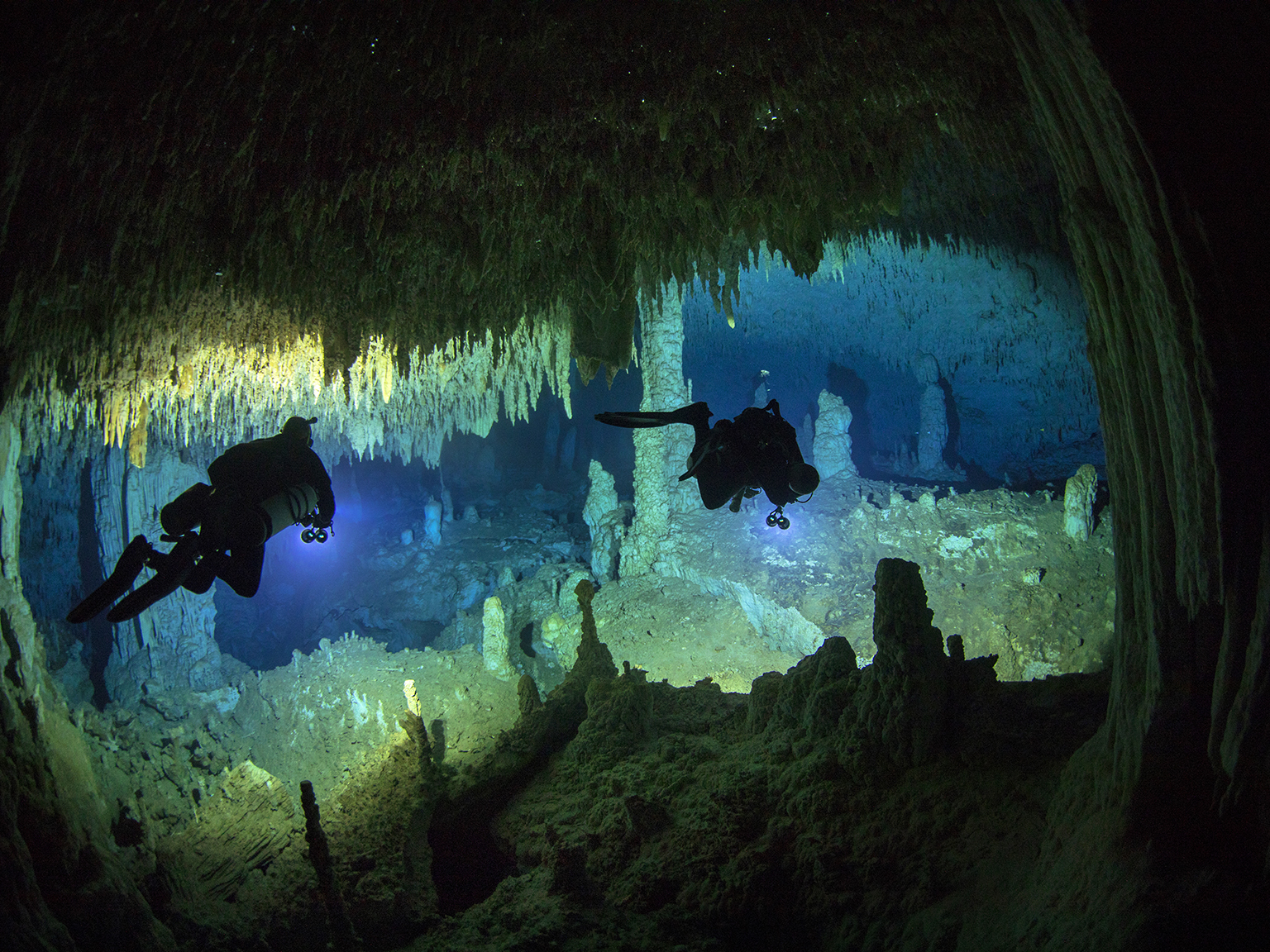

Cave diving has claimed more lives than Mount Everest, but Heinerth isn’t risking life and limb for the adrenaline rush. At 55 years old, she is on a mission to document the world’s underwater caves, the last great wilderness and one of the least-understood ecosystems on the planet. By fostering what she calls “water literacy” through visual storytelling, Heinerth hopes to illustrate our intimate connection with this precious natural resource.

“You can only protect what you know about and understand,” says Geary Schindel, president of the National Speleological Society. “Cave divers like Jill help bring caves and groundwater resources to the public’s attention. Otherwise, they would be out of sight and out of mind.”

Heinerth first fell in love with cave diving while a student at York University, where she pursued a bachelor’s degree in fine art with a focus on visual communication and design. In between a busy schedule as president of the student council and a member of several intramural sports teams, she found time to get her scuba certification by completing dives around shipwrecks near Tobermory, off the shore of Lake Huron.

On her final certification dive, Heinerth’s instructor took the group to a location known simply as The Cave. Going into overhead environments is typically considered an advanced skill that is off-limits to beginners. But as soon as Heinerth ventured past the cavern’s underwater threshold and into the airy anteroom on the other side, she was hooked.

“Beneath the rock ceiling, a single turquoise light ray sliced diagonally through the water ahead of me,” Heinerth recounts in her new book, Into the Planet. “Like a tractor beam, it pulled me forward and upward to float in the flickering light of a large open room. Somehow, I knew then that diving would be something I’d do for the rest of my life.”

Heinerth graduated from York with a Murray G. Ross Award, an honour bestowed on students for outstanding participation in undergraduate life, and soon found work at a graphic design office in Toronto.

She quickly parlayed her artistic talents into her own design company. Her business attracted high-profile clients like Nike and the Toronto Festival of Festivals, precursor to the Toronto International Film Festival. But despite her company’s success, Heinerth found herself unfulfilled. She belonged in the water and was determined to do whatever it took to turn her passion for diving into a career.

After taking night classes to become a scuba instructor at a dive shop in Toronto, Heinerth cut ties with her design agency and decamped to a dive resort on Grand Cayman Island. She spent a few years there cutting her teeth as a professional dive instructor before moving to the U.S., where she met cave-diving legend Bill Stone.

She was instantly on my radar as a rising star we could count on for future projects

At the time, Stone was searching for the world’s deepest cave in the jungles of Mexico, a treacherous pursuit that often involved diving in flooded passages deep below the Earth’s surface. In 1995, Heinerth accompanied Stone’s team to Mexico, where she helped set the record for the deepest cave explored up to that point.

“Jill came into that project as green as they come, but she came home impressing all of us, not just with her technical skill and cool head, but her overt enthusiasm for the entire endeavour,” says Stone. “It’s infectious when you work with such people. She was instantly on my radar as a rising star we could count on for future projects.”

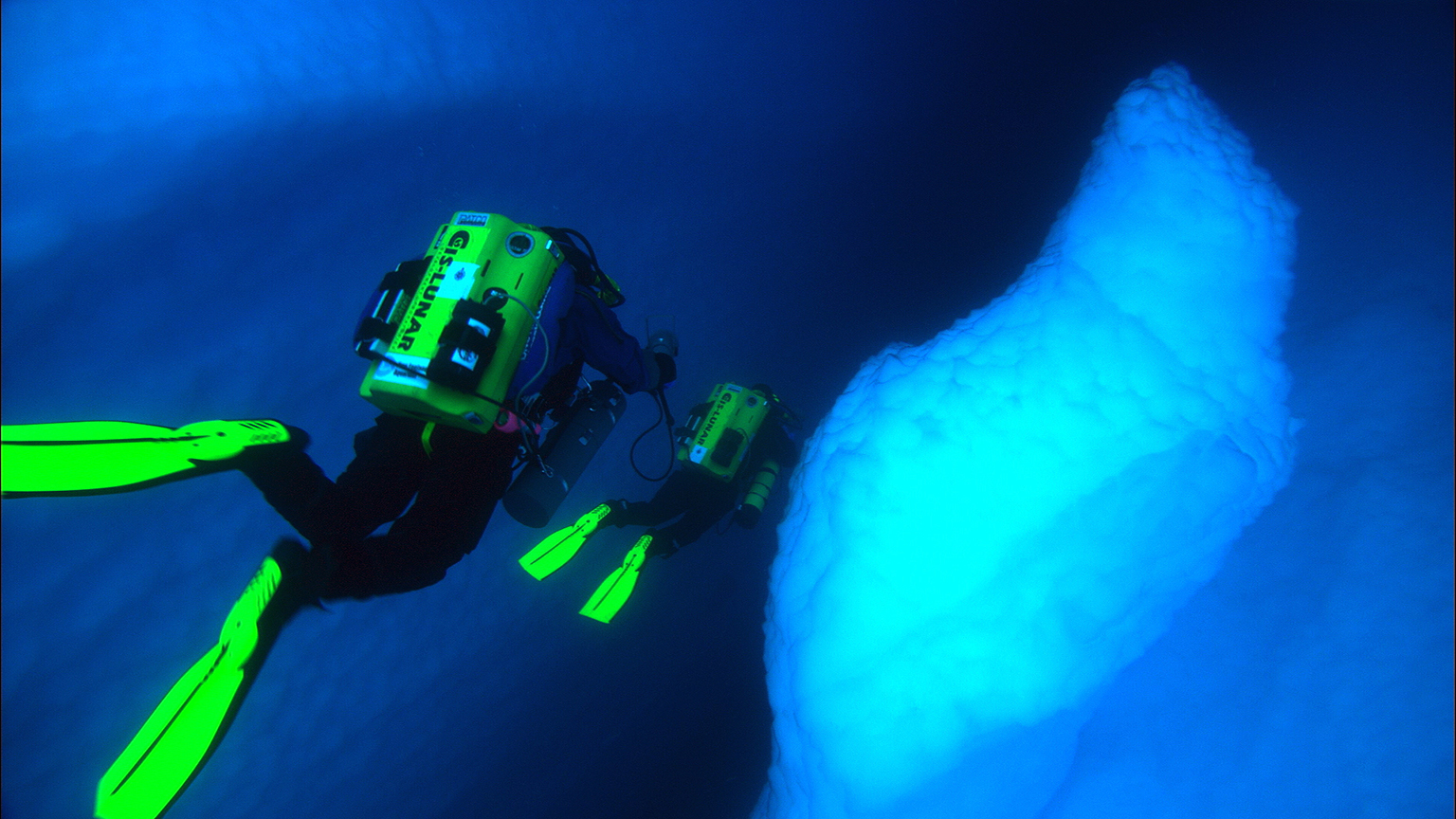

Heinerth’s trip to Mexico was her first real exploratory cave-diving expedition, and ultimately shaped the rest of her career. Since then, she has led the first team to dive into an iceberg, and was part of an elite group of Stone’s divers that became the first to create a 3D map of Wakulla Springs in Florida, an underwater cave system known as “diving’s Everest.” Along the way, she has written technical books on diving, produced several documentaries, and explored dozens of miles of unmapped terrain. And, in 2016, she was selected as the first explorer-in-residence at the Royal Canadian Geographical Society.

Heinerth’s early career as a cave diver was defined by the exploration of uncharted waters, but these days, she is focused on telling the human stories behind better-known underwater destinations. Widely recognized as one of the world’s pre-eminent underwater filmmakers, she recently returned from a documentary shoot at Truk Lagoon in Micronesia – the largest ship graveyard in the world, where thousands of Japanese soldiers perished during an Allied air raid during the Second World War. Next up is an expedition to document the wrecks off the coast of Newfoundland. “I want to focus more of my efforts on telling Canada’s underwater stories,” she says. “There’s a hidden geography there and I want to go deeper.” ■