View

The Print Revolution

by Joanna Thompson

photography by Horst Herget

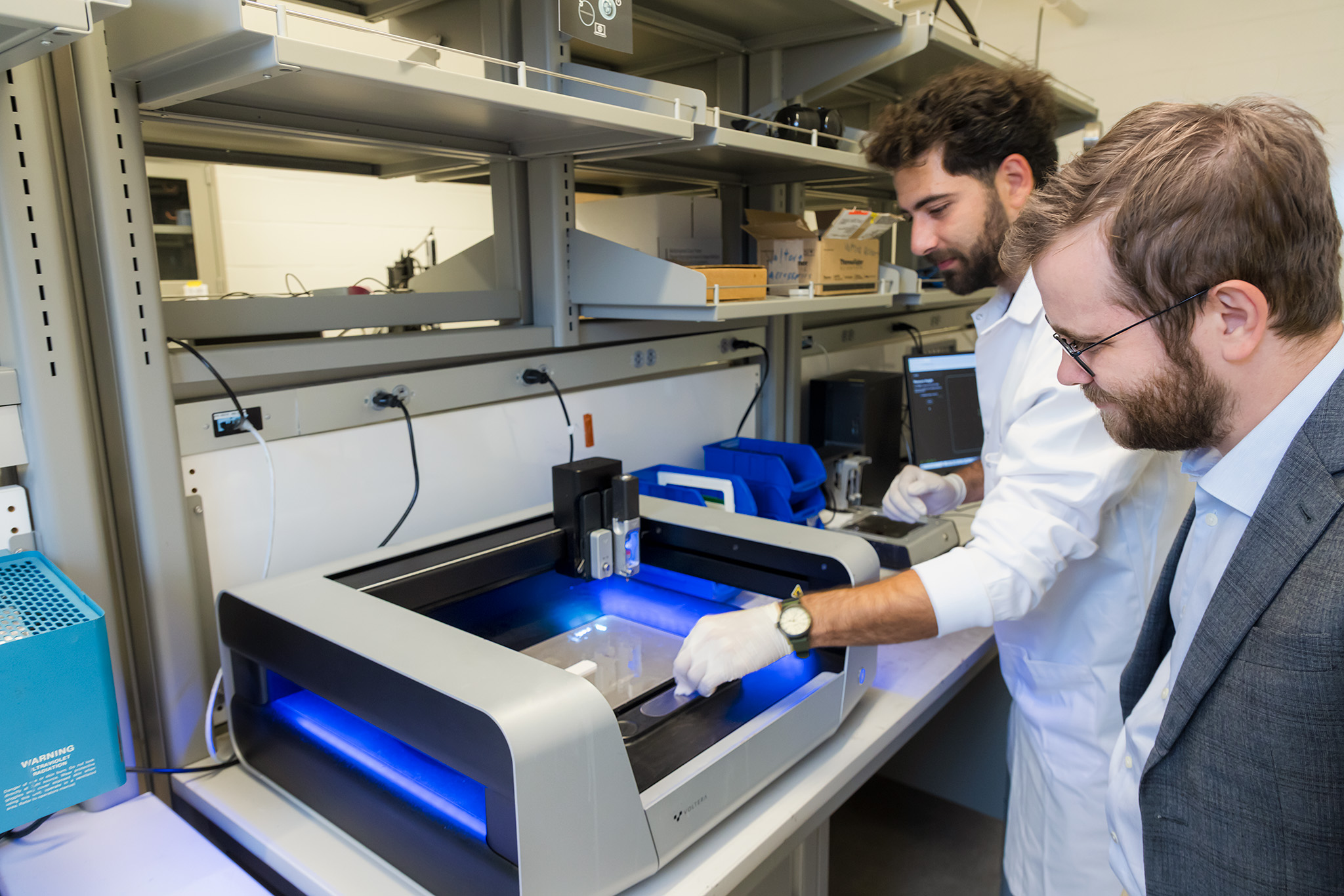

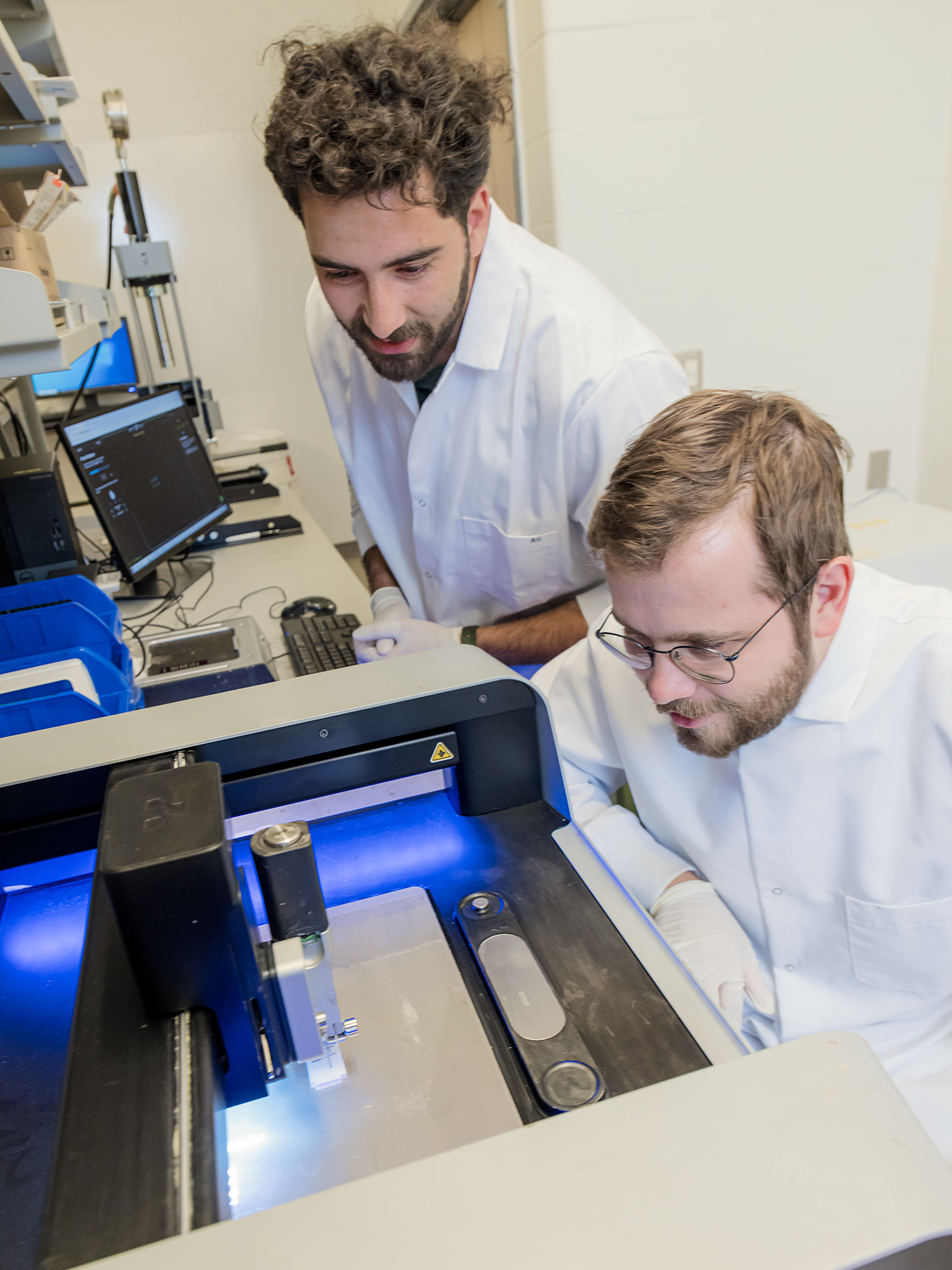

In a York University laboratory, a robotic arm glides back and forth, layering polymers so fine they’re nearly invisible. This isn’t just another demonstration of 3D printing’s potential – it’s the front line of a technological shift that could redefine how Canadians make everything from prosthetic limbs to wearable health monitors.

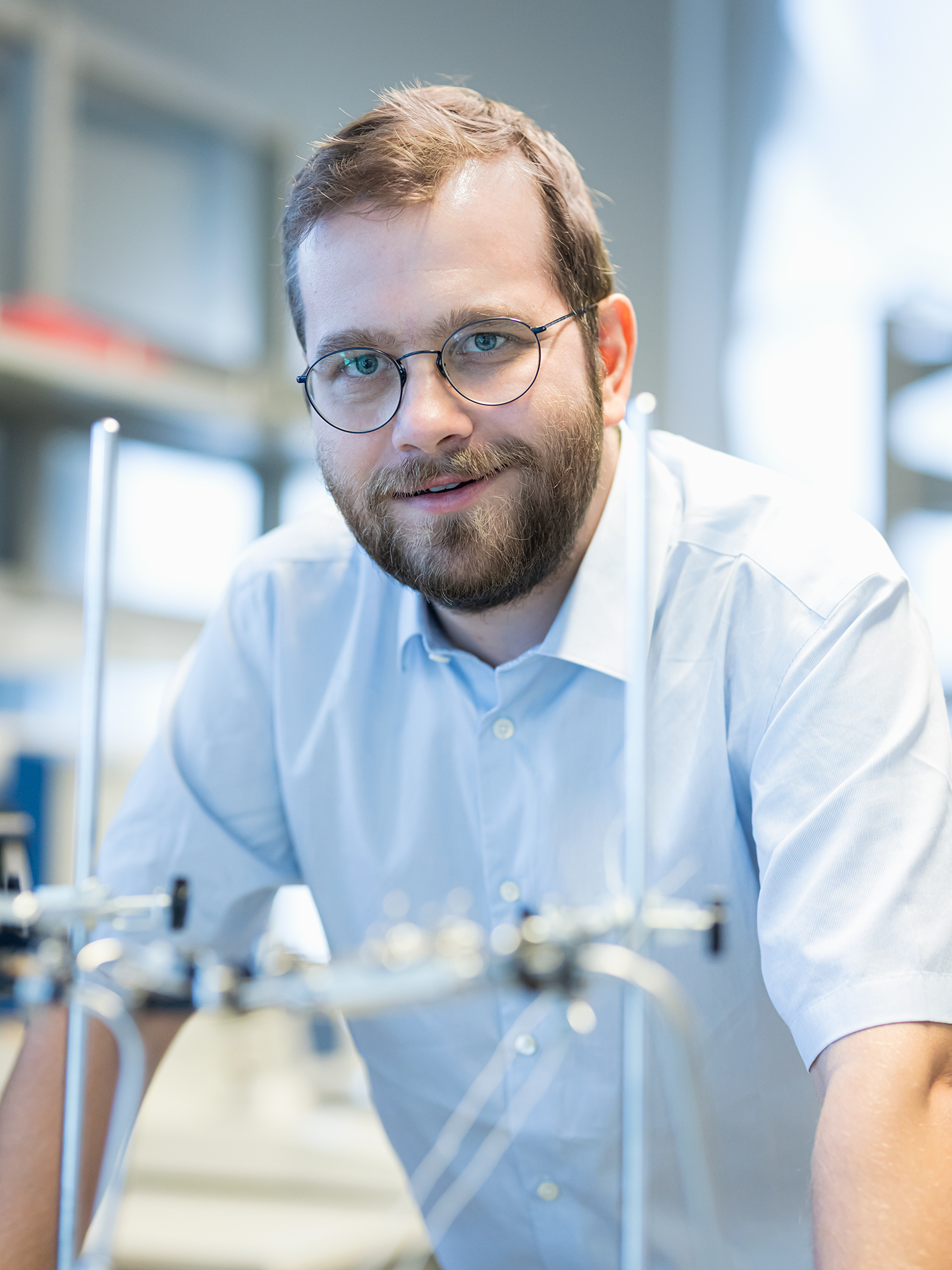

Professor Gerd Grau heads the Electronics Additive Manufacturing Lab (E-AM) at the Lassonde School of Engineering, where his team is merging two once-separate fields: additive manufacturing and printed electronics. The result is a new generation of devices that are not only custom-built for individual users, but also imbued with sensors and circuits that make them smarter and more responsive.

Consider prosthetics. Traditionally, manufacturing an artificial limb meant compromises – generic sizing, wasted material and high costs. Now, using 3D printing, engineers can tailor each prosthetic to the patient’s anatomy, reducing both waste and expense.

“With 3D printing, we can create prosthetics that are not only a perfect fit, but also produced more efficiently and with less environmental impact,” Grau explains.

But the innovation doesn’t stop at fit. By printing flexible electronics directly into the prosthetic, labs can add sensors and actuators without the bulk of traditional wiring. The result: lighter, more comfortable devices that can monitor pressure, movement or even send data wirelessly to a doctor.

The same technology is being woven – literally – into textiles. Imagine a T-shirt that tracks your heart rate and relays the information to your physician or smartphone app. It’s not science fiction; it’s a project already underway at York, made possible by printed electrodes and conductive inks.

The lab’s research extends to environmental challenges as well. Grau’s team is developing microfluidic devices to help recycle lithium from used batteries – a crucial step as Canada ramps up electric vehicle production. Even playful experiments, like a remote-controlled paper plane powered entirely by printed electronics, serve a purpose: pushing the boundaries of what’s possible with new materials and techniques.

These advances are quietly reshaping Canada’s manufacturing landscape. As automation and digital fabrication take hold, some traditional jobs may disappear, but new opportunities are emerging for those skilled in design, engineering and digital production. Institutions across the country are racing to update training programs to prepare workers for this shift.

Yet the transition won’t be seamless. The shift to advanced manufacturing is a work in progress. For every breakthrough in the lab, there are new questions about how these technologies will shape Canadian industry and the people who depend on it.

“Think of the current paradigm of electronics,” Grau says. “We are trying to come up with ways of manufacturing that are maybe orthogonal to that, but that basically enable new applications.” ■