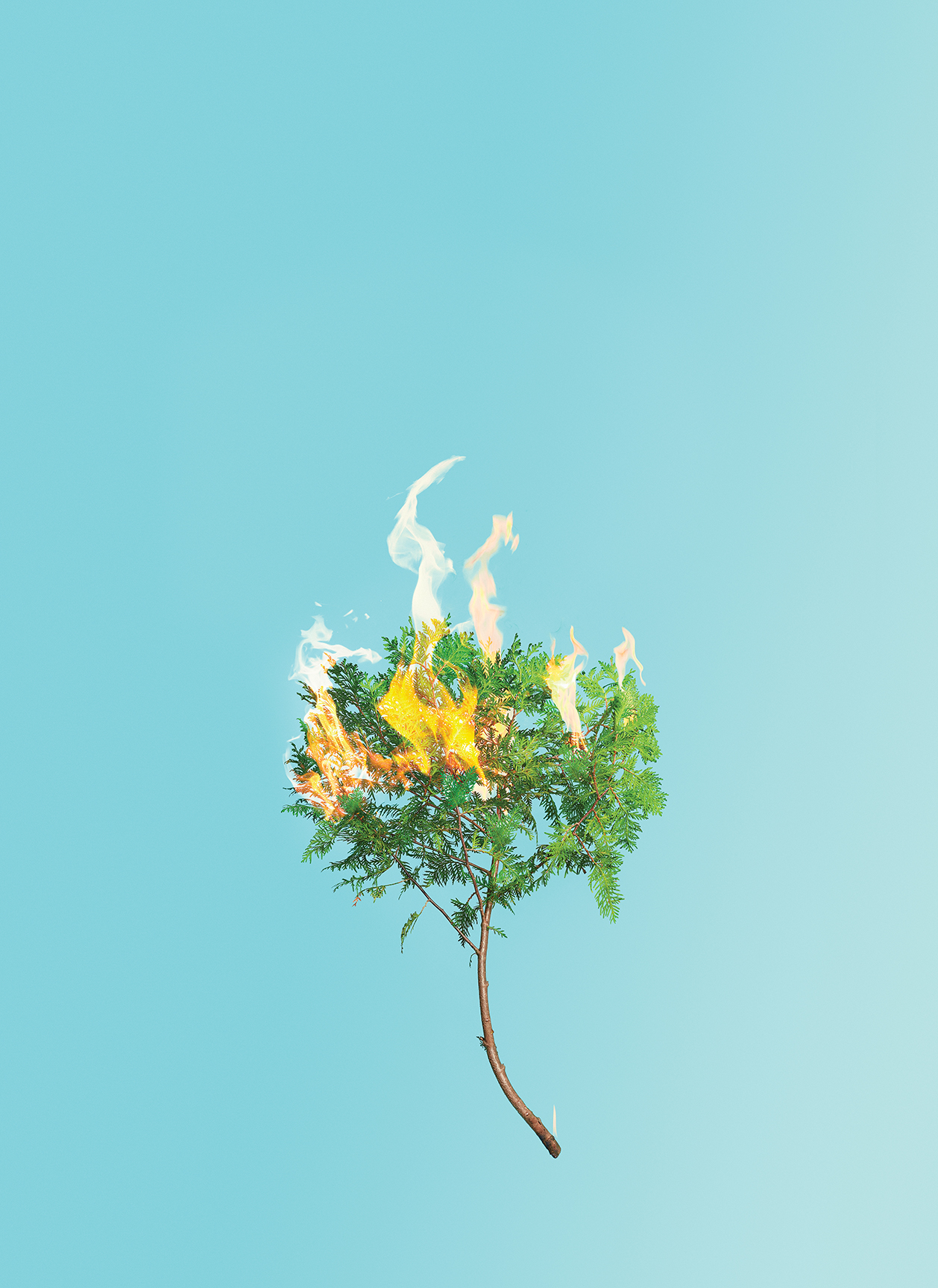

The Burning Season

by Deirdre Kelly

photography by Chris Robinson

On Aug. 30, 2017, a lightning strike ignited a small wildfire in the southeastern corner of British Columbia.

It simmered for almost two weeks before 100-kilometre winds accelerated its growth, driving it across the border into Alberta and straight through Waterton Lakes National Park.

Overnight, the conflagration consumed almost 33,000 hectares of Parks Canada forest and surrounding agriculture land. It also ripped through the Waterton Lakes National Park’s Visitor Centre, in addition to park maintenance and staff facilities and some other campground infrastructure, destroying them all.

Yet, as the smoke cleared, a more remarkable picture emerged: no public homes or businesses were lost within the Waterton town site.

For Eric B. Kennedy, an assistant professor in York University’s Disaster & Emergency Management program who studies wildfires, this was by far the bigger story.

As the native of Waterloo, Ont., explains it, while the Kenow fire was still smouldering in another province entirely, Parks Canada staff in Alberta had foam-sprayed buildings, cleared flammable debris, and collaborated with firefighters from Calgary, Lethbridge, Taber and Coaldale to try and protect buildings like the historic Prince of Wales Hotel.

They also convened town hall meetings, assisting in the evacuation of the town, and worked with wildland firefighters from Ontario to help battle the flames when indeed they did come.

These co-ordinated efforts ended up sparing both lives and residential properties.

“This is what can happen when you are prepared,” Kennedy says. “It’s an illustration of how the system can and should work.” And save money too.

New research shows that communities that protect themselves from future natural hazards like wildfires, hurricanes, earthquakes and floods can save themselves $11 for every $1 they invest in mitigation efforts.

Waterton is living proof.

With damages estimated at $22 million, the Kenow fire losses were far less than the 2016 Fort McMurray, Alta., fire whose estimated $10 billion in damages makes it Canada’s most expensive ever natural disaster – a striking contrast, even accounting for the difference in the cities’ sizes.

“The Kenow fire really demonstrated how much can be achieved by planning ahead, working together and being ready for wildfire,” Kennedy says. “We know a great deal about how to protect buildings and communities from forest fires, but that knowledge needs to be widely implemented to help reduce wildfire losses.”

The Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2019 lists York University as fourth in Canada and 14th globally in Climate Action, a category highlighting institutions that have taken urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts while strengthening resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries.

The University’s wildfire scholars include John Gales, an assistant professor in the Lassonde School of Engineering’s Department of Civil Engineering who leads York’s new Fire Safety Engineering Research Group, and Aaida Mamuji and Jack Rozdilsky, professors in Disaster & Emergency Management who look at civilian evacuations, including in Fort McMurray and in B.C., in recently published papers.

“We explore different aspects of civic evacuation, both through the lived experiences of evacuees and the receiving host community. The former is captured in our paper looking at the evacuation experience of the largest visible minority group in Fort McMurray, the Muslim community,” Mamuji says.

“Given the trend of increasing diversity within Canadian communities, having a better understanding of how the needs of diverse social groups can be met in crisis situations is necessary, as it facilitates a whole community approach to disaster and emergency management.”

Future research by the team will explore disability-inclusive emergency management, she says.

Gales also studies evacuations but from a transportation engineering perspective.

Earlier this year, he worked with students Lauren Folk and René Champagne to create a survey and computational model of a remote Canadian community as part of ongoing research into human behaviour and crisis management. Gales’s behavioural engineering research is done in collaboration with Arup, a multidisciplinary engineering and consulting firm with which Gales is working to help build resiliency guidelines for Canadian infrastructure.

The Kenow fire really demonstrated how much can be achieved by planning ahead, working together and being ready

“Our approach brings psychology and engineering together to create a conceptual framework on human behaviour based on real data from emergency evacuations,” he says.

Canada has long been a leader in wildfire research around the world for a simple reason: the country is extremely susceptible to them.

“Wildfires are a perennial feature of Canadian environments and burn annually in forests and grasslands from the Yukon to Newfoundland and Labrador,” says Kennedy, who joined Disaster & Emergency Management last July after completing a PhD at Arizona State University focusing on fire management practices across Canada.

“While busy fire seasons can shift from province to province in any given year, wildfires in Canada are as dependable as winter.”

Summer is typically the burning season, though wildfires can start as early as March and go on as late as October, depending on weather conditions. But summer heat and dryness remain primary factors.

Last year, an especially hot and dry summer contributed to the 220 wildfires that burned across B.C. over two days in July, forcing community evacuations and consuming over 1.2 million hectares – twice the size of the entirety of Prince Edward Island – of heavily forested land. This year, in the first weeks of June, the burning season got off to a ferocious start when wildfires in northern Alberta burned more than 283,000 hectares and forced 11,000 people to evacuate.

Managing and fighting these and other fires in Canada last year had an estimated cost of $1 billion.

Kennedy predicts that figure will climb even higher if people don’t change their relationship with wildfires, something he is attempting to achieve through his academic work.

“Wildfire has always been and will always be a part of our landscapes,” Kennedy says, “and if we choose to live in these flammable landscapes, we need to do so in a way that will reduce the potential for tragedy.”

But not all wildfires are necessarily disasters.

Research increasingly finds that there’s an advantage in letting moderate fires burn: they contribute to biodiversity and the sustainability of natural ecosystems.

Natural occurrences, wildfires reintroduce nutrients to the surrounding landscape, triggering forest regeneration and the growth of other plant species and providing new habitat for wildlife.

Regularly occurring, smaller and patchier fires can also help to create landscape patterns known as “mosaics,” where forests have a checkerboard of old and new growth – a condition that’s both ecologically healthier and more fire resilient than what results from suppressing all fires, Kennedy says.

Frequent burns can also help to reduce the potential for later catastrophic blazes by consuming old and decaying trees and debris.

As reported, the 2018 Boundary Valley fire burned roughly seven kilometres south of Waterton but was quickly suppressed, largely thanks to the efforts of Canadian and U.S. fire management resources.

“The 2017 Kenow fire burned much of the area to the north and west of this new area of fire,” said the Northern Rockies Incident Management Team in a press release.

“Reduced fuels in this recently burned area should help act as a fire break.”

In other words, you really can fight fire with fire. Science now backs that up.

Letting forests blaze (within limits) is a proactive approach increasingly being adopted by ecologists and governments who have come to understand that wildfires are often not just a fact of life, but ecologically necessary.

And alongside allowing lightning-started fires to burn, organizations like Parks Canada have been igniting forest fires as a matter of policy for some years now.

The government of Alberta’s prescribed fire program, for instance, is used “to restore ecosystems, restore healthy and resilient forests, and reduce the threat of large, uncontrollable fires.”

The fires are started under select weather conditions and managed in such a way as to minimize the emission of smoke and maximize the benefits to the site.

These prescribed fires can help prevent catastrophic blazes that are much harder to control. In these fires, it’s not just a matter of fighting the flames.

The blazes can also spread to human communities by means of embers carried on wind gusts and take hold in wood piles, decks, shingles, air vents and eavestroughs, transforming a tiny spark into a full-blown house fire.

From there, embers can even feed on homes and vehicles as fuel, propagating from building to building.

Just as at Waterton, preparedness is key in mitigating damages.

Kennedy says homeowner disaster and emergency plans can be simple, involving such routine tasks as raking up dead leaves, cleaning out eavestroughs, choosing less flammable building materials, and avoiding plants and wood piles beside the home.

“What Waterton shows,” says Kennedy, “is that fire preparedness is not a one-time thing. Not only do we have to think about how we build, but also about the risks faced by existing homes and how to maintain landscapes on an ongoing basis.”

In the wake of Waterton, Fort McMurray and the B.C. wildfires, he is also proposing that communities be designed with wildfires in mind.

Climate change, for one, is ensuring they are not going away.

“So much effort is often spent on putting out fires,” Kennedy says, “but a better approach might just be learning how to live with them.” ■