Rise Up

by Stephen Leahy

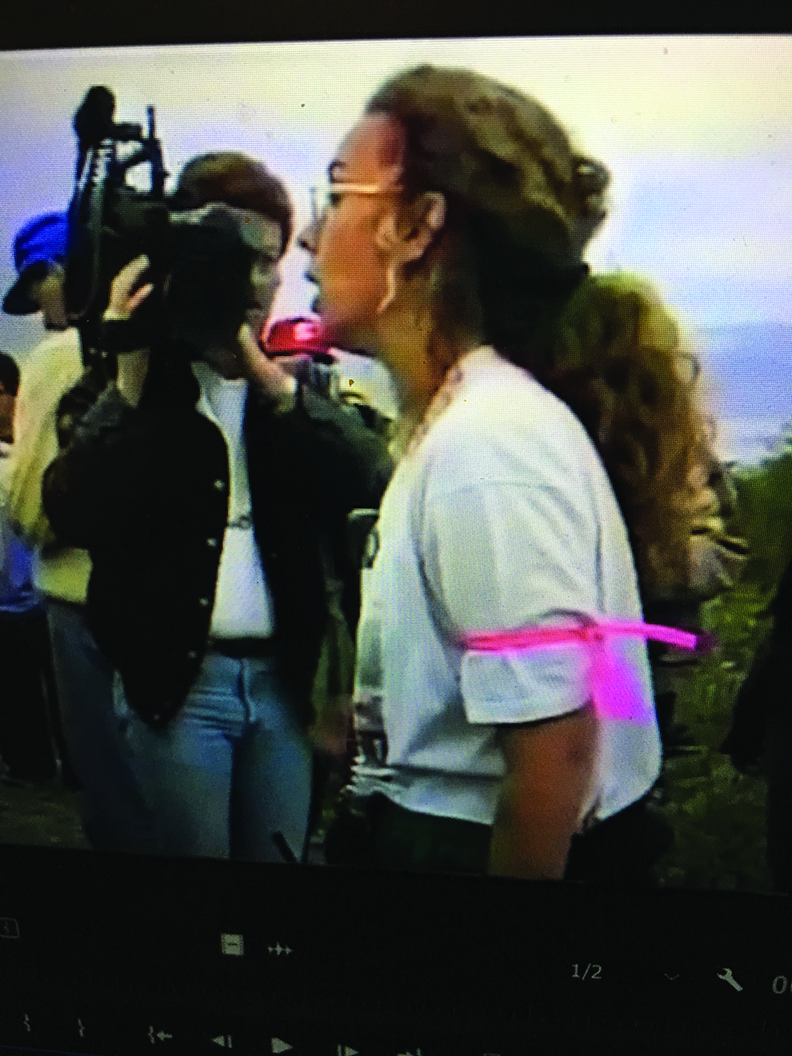

photography by Jaime Kowal

The mosquitoes were so bad in the summer of 2013 that Tzeporah Berman (MES ’95) and I actually choked on them trying to have a conversation. We were camped side by side in our respective tents, on the shore of Gregoire Lake, near Fort McMurray, Alta. It was my first meeting with the woman a British Columbia premier once called an “enemy of the state” and whom some of the world’s biggest corporations both fear and invite into their boardrooms. The same woman a few environmental activists labelled an “eco-Judas” for negotiating with those corporations. I liked her straight away. Berman, a York University grad and adjunct professor in the Department of Environmental Studies, is not the demon her critics would have you believe.

In her sleeping bag in the wilderness, Berman looked to be a kindly aunt taking her teenaged niece on a getting-to-know-you-better camping trip. But looks can be deceiving, especially when your vision is occluded by swarms of blood-sucking insects. In reality, Berman and her young charge were on the shores of Lake Gregoire to participate in the Tar Sands Healing Walk, a 14-kilometre trek led by Indigenous spiritual leaders through the bitumen production landscape in the Alberta oil sands.

“Welcome to the Land of Mordor,” Berman said at the time, referencing the hellish lands described in J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. (She does have a sense of humour.)

The oil sands drew Berman back to Canada in 2012 after working with Greenpeace International in Amsterdam on climate change issues. But she is perhaps better known for her prominent role in the anti-logging protests in Clayoquot Sound, B.C., in the 1990s. The struggle became known as British Columbia’s “War in the Woods” and was the largest act of civil disobedience in Canadian history at the time.

Positioning herself at the forefront, Berman, a 49-year-old native of London, Ont., now residing on the West Coast, was arrested and jailed. But the threat of prison never has deterred her. Just this summer, Berman was back at it, organizing the protest against the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion at the Kinder Morgan facility in B.C.

“The Crown has made it clear that they’re arguing for jail time if you oppose this project, but I think many people will stand up and continue to oppose this project. I’ll be one of them,” a defiant Berman told CTV News in June of this year. As she was speaking to the media, 17 people had already been arrested. More said they were willing to serve jail time if it’s what it takes to stop construction.

York encouraged me to get out into the world

But protestors were spared that fate when at the end of August the Federal Court of Appeal overturned the Trudeau government’s approval of the contentious Trans Mountain pipeline expansion for not having conducted “sincere and meaningful consultations” with Canada’s Indigenous people. The court also ordered the National Energy Board to look at the environmental effects of more tankers in the waters off B.C.’s coast, including their impact on endangered killer whales. The expansion project isn’t dead yet, and delays will be costly. Still, Berman sees it as a minor victory.

Later, when we spoke over the phone – no mozzies interrupting our conversation this time – she credited York University for teaching her to stand up for what is right. No matter what the cost. “York encouraged me to get out into the world,” she said. “I’m continuing the journey it set me out on.”

Berman had first arrived at the Keele Campus in 1993 to pursue her master’s degree in environmental studies. But there were distractions. The following summer she went back to Clayoquot Sound to become one of the most prominent activists in the “War in the Woods.” “Along with thousands of others,” Berman told me, “I found my voice at Clayoquot Sound.”

At Clayoquot, Berman was arrested, jailed and charged with 857 criminal counts of aiding and abetting the arrested protestors. The widespread media coverage triggered a formal petition to have her kicked out of York. “Their beef was that I was bringing the department into disrepute because of the blockades and all the charges against me,” Berman explained, “but my professors, Leesa Fawcett and Cate Sandilands, both fought for me. That was in 1994. Nothing ultimately came of it. I’d realized that scientific research wouldn’t stop the logging. Blockading seemed the right thing to do.”

“Tzeporah has tremendous resolve,” says eco-activist Valerie Langer, who mentored Berman during those early years at Clayoquot Sound. “She has been the target of some of the most vile and vitriolic criticism through her career and yet she perseveres.”

Berman eventually won her court case, and after graduating from York joined Greenpeace with a goal of ending clear-cut logging in Clayoquot Sound and other parts of the province. To help get the word out, she co-founded ForestEthics, a grassroots protest group using the power of the media and the threat of consumer boycotts to help persuade companies to become more sustainable.

In one campaign, Berman and company placed a full-page ad in the New York Times showing a Victoria’s Secret model holding a chainsaw. The eye-catching $30,000 ad communicated that the paper Victoria’s Secret catalogues were printed on came from critical mountain caribou habitat. The tagline was “Victoria’s Dirty Secret” and it worked.

She’s a very valuable Canadian. Tzeporah is what I think of as an academic-style advocate, which is rare

As widely reported at the time, after being besieged by more than 10,000 letters from across the U.S., Victoria’s Secret opted to find other suppliers. Berman wrote about this early triumph and her other acts of civil disobedience in her 2011 book, This Crazy Time, which tells her story from the 1993 logging blockades through to her work with ForestEthics. It earned her even more fans.

“She’s a very valuable Canadian,” says Mark Jaccard, an energy policy expert at Simon Fraser University. “Tzeporah is what I think of as an academic-style advocate, which is rare.”

Entering corporate boardrooms armed with scientific data and backstopped by the threat of boycotts, Berman and colleagues have worked with some of the largest companies to ensure their paper and wood product purchases are sustainable. These efforts have helped change the way forestry is done, not only in B.C. but also across Canada, resulting in the protection of millions of hectares of old-growth forest.

For her steadfast dedication to protecting the environment, in 2013 Berman was awarded an honorary doctorate of law from the University of British Columbia. UBC’s Sally Thorne said at the time that Berman was being honoured for her leadership “in shifting activism into an active and constructive engagement with leaders in industry.”

Since then, Berman has worked as a “consultant activist” for environmental groups and First Nations, advising on climate and energy issues. In 2015, the B.C. government asked for her help on creating a new climate policy, 20 years after another B.C. government had publicly called her an enemy of the state. Then, in 2016, the Alberta government appointed her co-chair of the Oil Sands Advisory Group to design a climate plan for the oil sands.

That controversial appointment made her the target of violent threats. She had experienced such hostility and more as a young anti-logging protestor 25 years earlier. Once again, she would not be deterred. After leaving the Oil Sands Advisory Group in 2017, Berman has been concentrating all her energies on opposing the Trans Mountain pipeline. Again, not without controversy.

The system is broken. This is the decisive decade to really take action

For those who have not been following the news, earlier this year the federal government bought the pipeline from its Texas-based owner, Kinder Morgan, spending $4.5 billion to buy it and other related infrastructure to ensure the pipeline expansion is completed. The original Trans Mountain pipeline had been built in 1953. Its current capacity is 300,000 barrels a day. The expansion would allow the system to send 890,000 barrels of different types of oil products from Edmonton to Burnaby, B.C., a day. The government thinks this is a good thing. Speaking to the CBC in June, Finance Minister Bill Morneau called the purchase an investment in Canada’s future, saying the pipline will preserve jobs, reassure investors and get Canada’s resources to world markets.

But Berman doesn’t think so. She claims that the proposed pipeline tramples on Indigenous land rights and poses a concern to the enviroment. It also represents a betrayal by government, she says. The proposed pipeline would pump oil sands bitumen to ocean-going tankers on the B.C. coast, risking possibly irreparable damage. Berman is not willing to let that happen without a fight. It’s not mosquitoes she is swatting away this time. It’s the politicians.

“The system is broken,” she said as we concluded our catch-up call. “This is the decisive decade to really take action on climate change to keep our kids and grandchildren from living in world where they might have to scramble to survive.”[end]

(With reporting and contributions from Deirdre Kelly)